Big Themes for 2024: Normalization, Differentiation, and Phasing-In Profitable Growth

Corporate Strategy

As we start 2024, distortions from the COVID era are finally receding; the world is normalizing. The over-arching big themes we see for both traditional and new energies this year are normalization, differentiation, and phasing-in profitable growth. A focus on profitability alone in and of itself is no longer differentiating for traditional energy names. A focus only on growth but without a clear path to eventual unsubsidized profitability is no longer acceptable for new energies. At its core, a sustained profitability advantage is about the pursuit of unique (i.e., non-commodity) business strategies that will distinguish leaders from laggards.

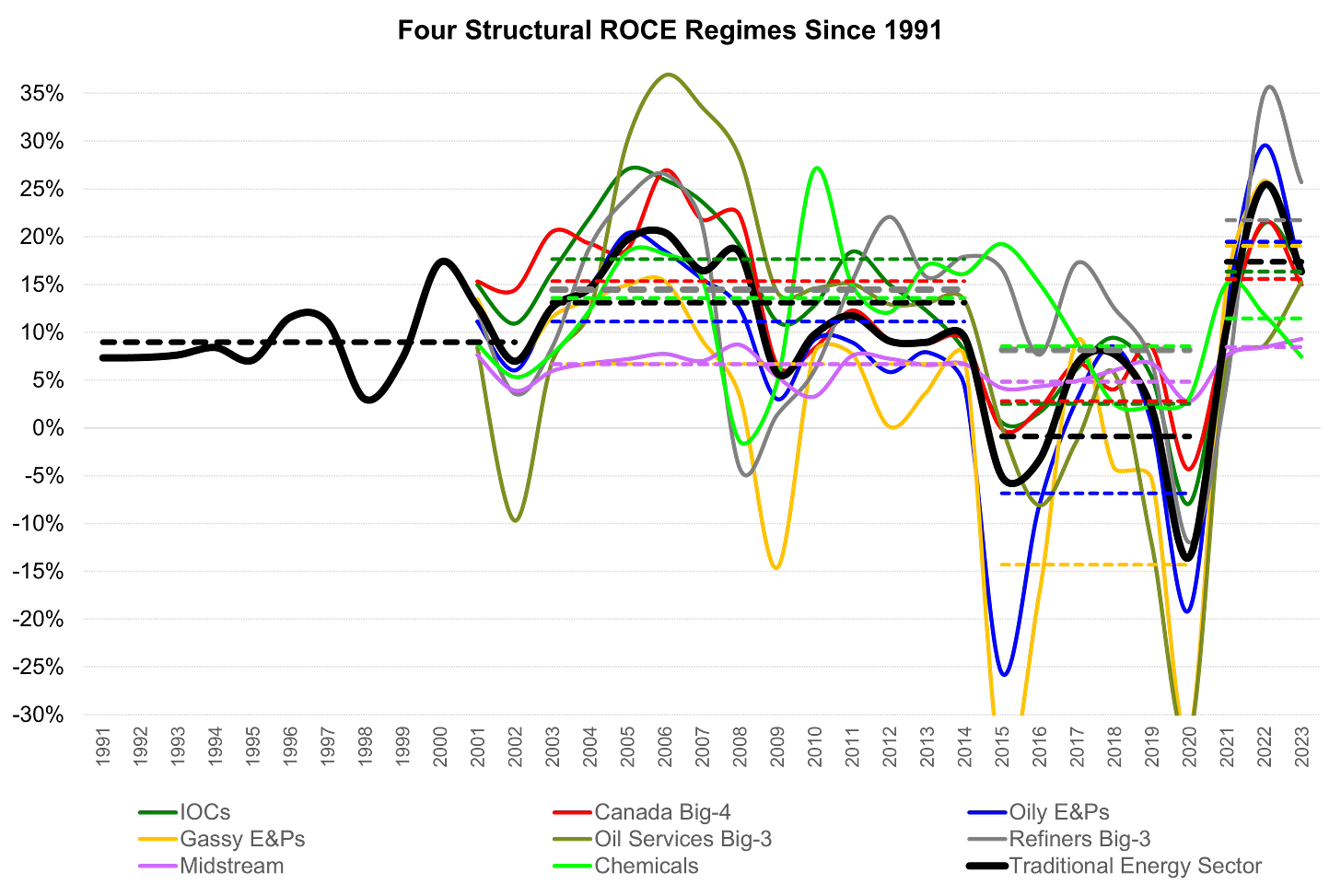

Within the normalization theme, traditional energy profitability has now definitively returned to levels competitive with the broader market after a terrible last decade punctuated by the deep COVID trough in 2020 (Exhibit 1). However, the improvement in sector weighting seen in 2021 and 2022 stalled in 2023 as investors doubted that profitability would sustain over the long run (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 1: Traditional energy ROCE has returned to competitive levels

Note: “Traditional Energy Sector” shown above excludes Midstream and Chemicals.

Source: FactSet, Veriten

Exhibit 2: Energy historically "punched its earnings weight" in the S&P 500, but now looks inexpensive

Source: Bloomberg, Veriten

While short-term recession concerns (which ultimately did not materialize in 2023) and a sequential pullback in commodity prices would naturally be expected to weigh on short-term share price performance, we see two longer-term overhangs that also played a major role in the lackluster performance:

Top-of-mind investor debate as to whether oil and natural gas demand is facing an imminent peak as new energy sources and technologies ramp-up.

A dearth of positively articulated outlooks from many traditional energy companies, as much of the sector remained in a defensive posture following the challenges of last decade.

On the second point, we believe the super majors (US and Europe) and some mega-cap non-integrated oils are in the early stages of strategy differentiation. We believe the US "Big 3" refiners also appear to have unique opportunities to sustain competitive profitability. It is the broader mass of non-super cap E&Ps where it is much more difficult to sort out who is on-track to perpetuate advantaged profitability over the long run. In terms of exposures, with premium acreage in the Permian Basin seemingly in the later stages of a major consolidation phase, for most companies it will be about looking elsewhere. Possible areas of interest include Canada's oil sands region, the Montney (Canada), global LNG, Tier 2/3 US shale plays, international business development (e.g., Argentina? Africa?), and exploration.

For the new energies spaces (i.e., alternative energy), it is about sorting through the carnage that marked 2023 and figuring out which business models are capable of achieving scale without an over-dependence on government largesse (i.e., subsidies). We see substantial volume growth potential in a broad range of new energies; however, the best areas for un-subsidized profitability are not yet clear to us. Given the early-stage nature of many new energies areas, this is not surprising. But it also speaks to the lack of pragmatism for those that believe a fast "energy transition" away from fossil fuels and into new energy sources is possible within some arbitrarily short time frame (i.e., next 20-30 years). We will need all forms of energy in the coming 25, 50, and 100 years in order to meet the substantial energy needs of everyone on Earth.

We should be clear that investing in subsidized projects can make sense for individual companies; it is the timing and magnitude of massively scaling-up those areas to displace traditional energy that we question when businesses are dependent on excessive government support. Given the potential for US Federal Reserve rate cuts in 2024, it would not surprise us if "growth," including "unprofitable growth,” caught a bid at various points in 2024. We leave short-term trading calls to the current crop of Wall Street professionals. Our focus as always is on the prospect for long-term value creation.

Peak oil and gas demand: No where in sight

We will keep this section brief since Super-Spiked readers are by now well familiar with our view: we do not believe it is yet possible to determine the decade, never mind year, when oil or natural gas demand will peak let alone enter terminal decline; we see trend growth on the order of 0.75%-1.5% per annum for oil and 1%-3% per annum for global natural gas for the foreseeable future.

It defies credibility and commonsense to think one can limit rich-world status to only The Lucky 1 Billion of us living in the USA, Western Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand; the other 7 (soon to be 9) billion people on Earth have massive scope to improve living standards by using substantially more energy than is currently the case. In order to meet ultimate global energy demand, we believe all forms of energy sources and technologies will be used.

Moreover, for countries that are short (i.e., do not have) oil and gas resources, we see a strong motivation to diversify into new energies areas and limit dependence on imported oil and natural gas. It is not "energy transition due to climate concerns" that we think will motivate the development of new energies; it is instead the traditional drivers of ensuring energy abundance, affordability, and geopolitical security that will drive individual countries to develop and implement a broad array of energy sources and technologies beyond traditional oil, natural gas, and coal.

Does the oil & gas industry believe in its own future?

Beyond the debate over long-term demand trends, we would observe that for traditional energy companies, positively articulated equity stories are generally speaking in short supply. After a challenging last decade, we understand the emphasis has been on improving profitability, restoring balance sheet health, and returning excess cash to investors—all steps that were desperately needed over the past three years. But that phase is over. If investors are to ever return en masse to a sector whose market capitalization weighting is still badly under-punching its earnings contribution, companies will need to demonstrate and articulate how they are contributing to meeting the world’s energy needs with low cost-of-supply investments that will allow advantaged profitability to continue.

If there is ever a case for diversity, it is in the strategy choices companies make:

Does your company agree that there is no peak in sight for oil or natural gas demand or are your business plans instead based on a more pessimistic outlook for traditional energy eventually transpiring within the next decade or so?

What is your unique competitive advantage in what is a commodity sector?

How do you overcome inevitable cyclicality, especially as we expect a "Super Vol" macro backdrop to persist for the foreseeable future?

What are you doing to ensure you can outperform commodity prices over the long run as opposed to simply riding the ups and downs of the cycle?

How do you focus on the best decisions to ensure long-term competitive advantage while maintaining needed institutional investor support over the short-term?

Why are so many companies seemingly content with looking and sounding like many of their peers?

It is worth emphasizing the point about outperforming commodity prices over the long-run as going part-and-parcel with going-concern valuation credit and sustainable value creation. A commodity business in aggregate, by definition, will earn its cost of capital—no more, no less—over the long run (rolling 10-30 years). We believe 150 years of history for the traditional energy space proves this point beyond any doubt; we refer readers to The Crude Chronicles (here) for the only research we are aware of that tracks sector profitability back to the industry's founding with Standard Oil Company. The goal has to be to outperform commodity prices over the long run, even as short-term volatility will invariably drive corresponding fluctuation in the near term.

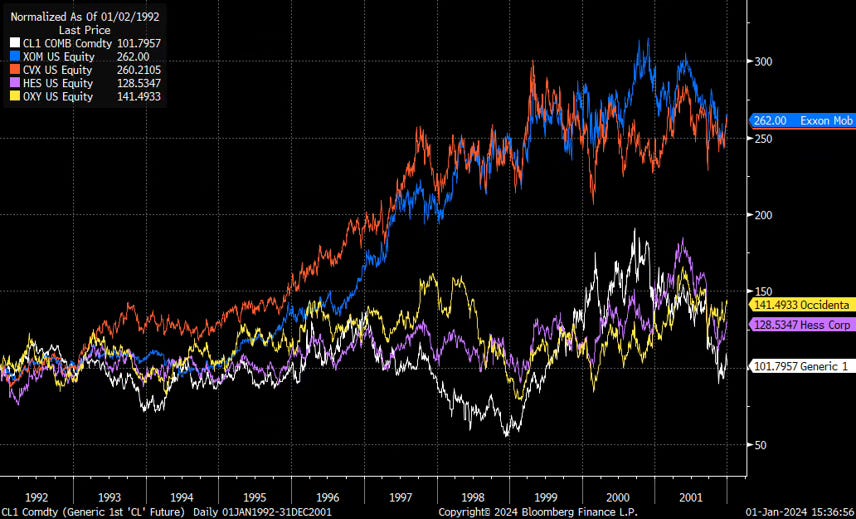

Exhibits 3-5 illustrate three time periods and the difference in share price performance between “riding the cycle” versus more meaningful outperformance. Given that we wanted to show the different eras over the past 30 years with some consistency and an ability for current readers to relate, we have chosen four companies that have been around over the full time frame to make our point—ExxonMobil (Exxon), Chevron (ChevronTexaco), Hess (Amerada Hess), and Occidental Petroleum.

Exhibit 3 shows that Exxon and Chevron significantly outperformed lackluster oil prices during the 1990s, as both focused on restructuring and rejuvenation strategies with an over-arching focus on improving return on capital employed (ROCE). In contrast, Amerada Hess and Oxy shares simply rode the ups and downs of the oil price cycle and generated much weaker ROCE vis-à-vis Exxon and Chevron.

Exhibit 4 shows that Oxy was the big winner in the 2000s following a late 1990s restructuring effort that also saw it make major oil resource acquisitions in the Permian Basin and California at what turned out to be a low point in the oil cycle. During the Super-Spike era, Oxy shares benefitted from both expanding ROCE and oil-leveraged growth.

Exhibit 5 shows that since 2015, Hess has been the big winner owing to its exposure to massive low-cost oil discovered offshore Guyana, a massively differentiated opportunity that was very material to its share price.

Exhibit 3: 1990s: Exxon and Chevron significantly outperform oil price

Source: Bloomberg, FactSet, Veriten

Exhibit 4: 2000s Super-Spike era: Occidental significantly outperforms oil price

Source: Bloomberg, FactSet, Veriten

Exhibit 5: Post-Super-Spike bust to current Messy Energy Transition Era: Hess significantly outperforms oil price

Source: Bloomberg, FactSet, Veriten

Table stakes are not sources of competitive advantage

Just about every traditional energy company has bought into the following:

Focused on sustaining or improving profitability as measured by ROCE or similar corporate-level metrics

Generating free cash flow at mid-cycle or higher commodity prices, with a meaningful portion of excess cash to be returned to shareholders

Maintaining or aspiring to a "fortress" balance sheet

Collectively, these are now table stakes in terms of financial objectives. It is worth pointing out that each of these metrics—which we are strong proponents of focusing on—represents the outcome of a successful strategy. Good investments drive good returns. Over-investment runs the risk of ruining good returns. Under-investment, paradoxically, will also ultimately lead to a weaker outlook if an advantaged asset base is not, at a minimum, maintained.

The financial promises have been supplemented by just about all energy companies with what we might call modern day "declare you will do no evil" pledges around net zero by a round number year, near zero methane even sooner, and various other so-called "ESG" (environmental, social, governance) promises. Similar to the financial promises, the various climate and ESG goals are now table stakes and not differentiating for the most part.

Regarding ESG as a concept, as we have commented on previously, it is unfortunate that substantive ESG has been over-run by "climate only" ideologues and related progressive (US political context) causes, which are now facing reflexive backlash from the US right. It remains our view that substantive ESG is endemic to successful companies. The left-wing (i.e., progressive) political orientation of ESG is what needs to go away. The right-wing counter that all ESG is a grift in our view fails to differentiate between relevant concepts (e.g., governance is indisputably a critical focus area for all investors) and the problematic portions of current-day ESG.

Sub-sector competitive advantage assessment

Below we provide an initial summary assessment of the opportunities for differentiation and to phase-in profitable growth by sub-sector. We intend to elaborate on this section in future posts.

Super major and mega-cap non-integrated oils

The Super Majors and mega-cap non-integrated oils we believe are appropriately focused on regaining "going concern" valuation status, which we will short-hand as trading at 80%-90% of the S&P 500 market multiple using P/E (price/earnings) versus circa 50% currently.

The fact that these companies are global, have large balance sheets, and a range of technical and engineering skillsets point to a wide range of opportunities that are pursuable. The downside is the need for scale investments, which might limit opportunities to pursue various niches.

A mixture of M&A, organic growth, and business expansion in both traditional and newer areas will be the focus, but where no singular area or growth driver dominates.

Diversification by asset type and region provides regular opportunities for counter-cyclical investing or pressing an advantage in an up-market.

This group of companies will look to evaluate opportunities in new energies that fit their skillset.

US Big-3 downstream

We find the trio of Marathon Petroleum, Phillips 66, and Valero Energy to be perhaps next-best positioned after the Super Majors and mega-caps to earn "going concern" status driven by the potential to sustain advantaged, albeit more volatile, profitability over the long run.

If concerns about peak oil demand are weighing on upstream CAPEX, one can be sure there is even less appetite to add major new refining capacity around the world.

Barriers to entry are high.

Somewhat surprisingly, US downstream has more logical adjacencies to various new energies opportunities than we believe is the case for most E&P pure plays.

US midstream

Somewhat similar to the US Big-3 downstream companies, exposure to various pipelines, terminals, natural gas liquids (NGLs) processing facilities, and export terminals creates a unique opportunity set for the midstream space.

Historic profitability is lower than for other areas but also far less volatile. The lower inherent volatility likely argues for a return on equity (ROE) focus rather than ROCE (we will look to further evaluate this in a future post).

With both new and traditional energy requiring significant infrastructure support, we suspect there is logic to midstream companies evaluating a range of opportunities.

SMID-cap E&Ps

SMID-cap E&P is invariably about exposure to and exploitation of a niche, be that regional or by asset type.

The role of M&A as a buyer or eventually as a seller is usually more pronounced.

Figuring out where one is in the duration of the advantaged opportunity is a critical assessment point (is it early, mid-cycle, or late for your area).

SMID-cap refiners

In some respects, there is common ground between SMID-cap E&Ps and SMID refiners in that it is typically about exploitation of a niche strategy.

We suspect the opportunity for SMID-cap refiners to consider new energies is greater than for SMID E&Ps.

Like the US Big-3, SMID refiners benefit from the high barriers to entry in US refining.

New energies

This needs to be broken out by all the various sub-sectors: residential solar, utility-scale solar, geothermal, nuclear, wind (onshore and offshore), electric vehicle manufacturing, electric vehicle infrastructure, minerals and mining, grid infrastructure, energy storage, carbon capture and storage (CCS), direct air capture (DAC), and many more areas we have undoubtedly not listed here.

It is for a future post.

⚡️On A Personal Note: "Have a questioning attitude"

One of the best parts of the holiday season is being able to catch-up on a backlog of podcasts, books, and other content that accumulated over a busy Fall travel season. One podcast originally published in August 2023 (here) that stood out featured a well-regarded physicist interviewed by the American Museum of Science and Energy (AMSE), Dr. Venkatesh Narayanamurti, better known as “Dean Venky” from his time as the Founding Dean of Harvard University’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (background).

The key punchline came at about the 24-minute mark and is the idea that great scientists will always “have a questioning attitude”:

What you always have to ask: What is it that I do not know? What is it that I do not understand?” What is it that I want to build? So, it is (to have) a questioning attitude.

– Venky Narayanamurti

It is exactly this point that I have always aspired to in my career as an equity research analyst. I would have never described my analytical style as being driven by a scientific approach to markets or the energy sector. Unlike many in my extended family, I preferred finance/business/markets to science (for a future OAPN: my circuitous route from Cornell’s College of Engineering to the University of Denver). But the discussion immediately resonated with me. If nothing else, I have always sought to have a questioning attitude about all things related to covering the energy sector. I have always sought to push back on consensus narratives, when appropriate. I have never looked to take management guidance or so-called expert opinion at face value. I have had and continue to have a questioning attitude.

The sad truth today is that having a questioning attitude, especially when it comes to energy and the environment, often gets labeled as being a denier or not sufficiently supportive of a particular agenda. Rubbish. I would encourage all Super-Spiked readers to have a questioning attitude.

Exhibit: Venkatesh Narayanamurti, physicist

Source: Indian Academy of Sciences

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Arjun,

Thanks, as always.

Does it really make sense to say developing countries will implement unconventional energy (wind, solar) to reduce reliance on foreign imports if the panels/windmills really only have a,say, 15 year life? (And then they have to import replacements?). China maybe being the exception?

This is an excellent summary which gives the reader much to ponder and research. In a piece like this, I seem to latch on to a given phrase/concept. To wit:

"however, the best areas for un-subsidized profitability are not yet clear to us"

As an investor, it's hard to avoid an attraction to sectors or companies which seem to be the recipient of boatloads of government giveaways. In that regard, do you have any opinion on an entity such as NPWR? Anyone claiming "Clean, Reliable, Low-Cost Energy" (front and center on the website) would seem to fit the bill as a worthy recipient. But does CCUS survive and thrive without a helping hand? Seems I've already read of huge push back from environmentalists regarding the process given the words "natural gas".

Any thoughts?