Stop trying to get Blockbuster Video — i.e. Big Oil—to accelerate energy transition

Crazy-idea-of-the-week: Free Big Oil to focus on producing needed oil and gas

One of the more perplexing energy policy objectives and rhetorical motivations pursued by some ESG investors and others particularly passionate about climate change is the obsession with Big Oil company energy transition CAPEX. Why does anyone believe capital spending by Big Oil companies is even remotely relevant to progress on moving away from fossil fuels? Big Oil companies are barely relevant to the oil business. Why would they be relevant to next generation energy technologies? What evidence is there in any sector of yesterday’s giants being tomorrow’s disruptors? And to the extent we may be in the early stages of an unfolding energy crisis, is it really that crazy to suggest Big Oil’s best purpose in life may simply be to help produce whatever oil and natural gas the world is still demanding?

Netflix versus Blockbuster Video

This one is obvious in hindsight, less so if you lived through the 1980s/1990s VCR era of movie watching. Its hard to remember but Netflix started as a DVD-by-mail company, added streaming, and then...well, I think we all know how it turned out. The core point: there is no part of Netflix’s success that required a legacy brick-and-mortar video rental business. They did not need those cash flows. They actually made some tough (at the time) decisions on toggling between DVD-by-mail and streaming, the prices they were charging, bundling/unbundling services, and so on. And execution was not perfect. But the ultimate results speak for themselves. And, somehow, streaming is now ubiquitous despite the failure of Blockbuster Video.

Amazon versus Barnes & Noble, Sears Roebuck and every traditional retailer

Since this is also a well known story, I’ll get to the point:

Amazon did not require a brick-and-mortal retail chain to sell books, or any subsequent product, online.

Amazon did not need legacy cash flows to fund its phenomenal growth.

Like Netflix, Amazon was nimble, was wiling to take risks, was willing to have failures along the way, and ultimately had the mindset of a disruptive growth start-up, not a bureaucratic, set-in-its-ways, risk averse establishment player.

Notably, online commerce has grown exponentially and has not in anyway depended on the CAPEX or success of old-line analog commerce players. Does anyone even know if Sears or Barnes & Noble are still around?

Tesla versus all other automakers

Perhaps the example best suited to the energy transition argument is Tesla versus every other Auto OEM. EV growth has long been the promised future, going back to at least the early 1990s and the various mandates pursued in California over many decades. The problem has been that Big Auto has thus far failed at making an EV anyone actually wanted to buy—see the Nissan Leaf, Chevy Volt, Chevy Bolt, etc. Tesla changed the narrative.

Like Netflix and Amazon, Tesla has not required legacy businesses to achieve exponential growth. And perhaps similar to other energy transition technologies, building electric vehicles requires a lot of capital, engineering and technology expertise, and production execution capabilities. On all these points, Tesla’s success has never been a foregone conclusion. “Production Hell” wasn’t that long ago. But the company worked through it despite having lacked any prior expertise (as a company) at mass production. And there were many capital raises at significantly lower stock prices than what we see on our screen today. Like other energy transition businesses, EV R&D and manufacturing is very capital intensive. It’s a good thing we didn’t have to wait for traditional Big Auto to prove an EV business model was viable.

This post is going to avoid jumping into the toxic debate about the appropriateness of Tesla’s current $1 trillion valuation. Whether justified or not, it is a fact (I imply nothing about my views as to the reasonableness of Tesla’s valuation via this or any other statement in this post). Tesla now has an S&P 500 weighting that approximates the entire S&P energy sector and it long ago passed all of Big Auto in market capitalization. In all of these revolutionary examples, I believe there is little question that all three companies were able to succeed because they were not tied to an old line of business or way of thinking.

While some will argue Tesla is simply a function of a giant stock market bubble, the fact is they are the dominant EV company in the world today and it’s not even a close call versus legacy “peers”. The stock may or may not be over-valued, but there is no disputing its cars are spectacular and dominating the market. (Disclosure: I have owned either a Model S or Model 3 since 2015 and will never again have an ICE vehicle as my primary ride.)

Has any old line leader transitioned successfully in any business in any era? Perhaps Microsoft or possibly Apple are examples of companies that led in one area and have adapted well to a new reality. I am sure there are others, but they too are the exceptions and not the rule.

Big Oil is not that big any more, Medium Oil is more like it

There appears to be a mis-understanding on the part of non-traditional investors, policy markers, and climate enthusiasts about the importance of Big Oil. The combination of BP, Shell, Total, Chevron, and ExxonMobil accounted for a combined 7.7 million b/d of oil production in 3Q2021, or just under 8% of a circa 100 million b/d oil market. At $1.16 trillion, Tesla’s market capitalization is larger than the $860 billion combined market cap of the Big Oil-5.

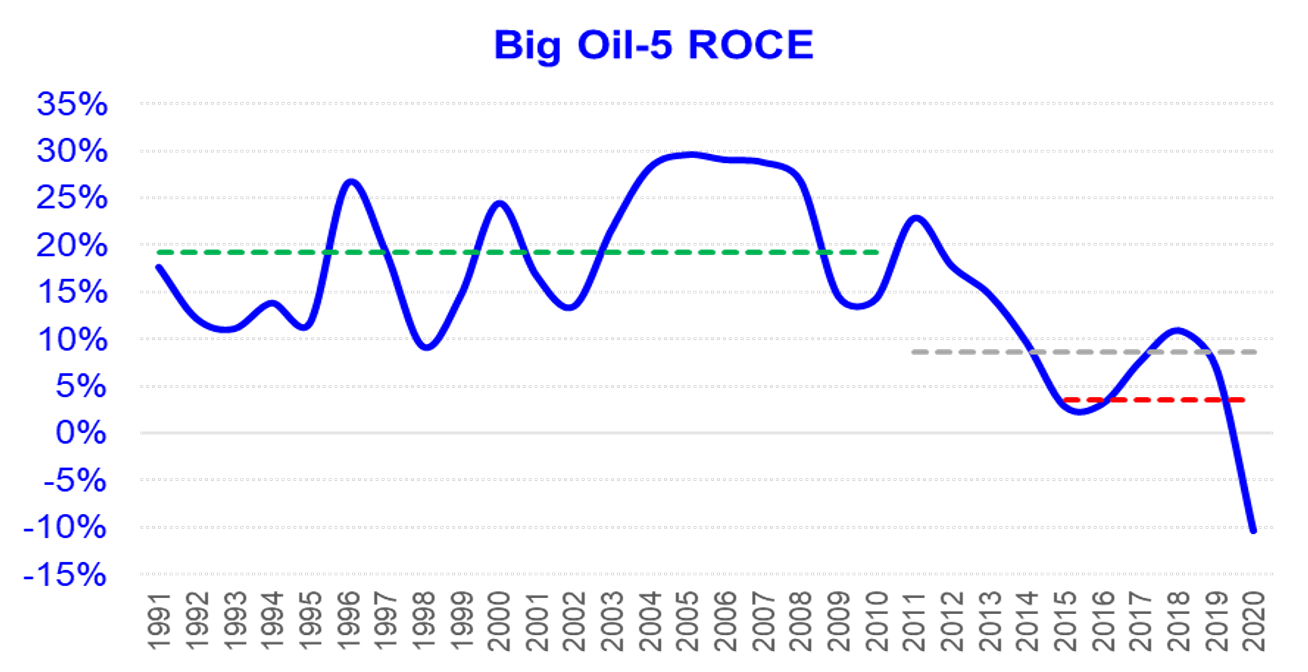

Big Oil ROCE has been poor in legacy areas, reducing confidence about spending in new areas

Over the last decade (2011-2020), returns on capital employed (ROCE) for the Big Oil-5 averaged 8.5% ($68 average nominal WTI oil price average over the period). More troubling, over 2015-2020, ROCE averaged a paltry 3.5% ($51/bbl WTI). There is an urgent need to improve profitability in the area it knows best. Prior to 2011, Big Oils actually generated quite competitive profitability, free cash flow, and shareholder returns. Over 1991-2010, ROCE for Big Oil-5 averaged 19% (pre-merger periods include only the surviving heritage company), which helped traditional energy remain a meaningful weighting in the S&P 500 until the post-2014 bust period began.

So what should Big Oil do?

The overwhelming first order of business for Big Oil is:

Produce as much low cost oil & gas as the world still demands at a full-cycle ROCE greater than 12% (preferably mid-teens or higher).

Grow oil & gas supply at a pace that approximates demand trends (some exceptions to this rule, such as Hess).

Return excess cash back to shareholders.

As the unfolding energy crisis portends, it is regular people the world over (i.e., non-global elites) that bear the brunt of ill-advised energy policy and market developments. Available and affordable energy is a fundamental right we all have, and crude oil and natural gas are likely to remain dominant primary fuels for many, many decades into the future.

Attracting and retaining investors allows for a healthy industry that enables oil and gas companies to grow supply at rates that approximate demand. I love capitalism. I hate socialism. If any company doesn’t have its own house in order, it is really hard to have confidence as an investor that they will somehow excel in a new business line where they likely do not have expertise or skills and often require a new mindset and business models. What evidence is there that Big Oil is well suited to transition?

How can Big Oil contribute to fighting climate change risks?

The areas where I think Big Oil can make the most meaningful contributions to address climate change risks are the following:

No methane flaring, venting, or leaks starting soon.

Figure out an industry solution to orphan wells and other blights caused by firms that no longer exist.

Work towards net zero on Scope 1+2 emissions by 2050 (or sooner). I will leave Scope 3 for a future post. Needless to say, the current accounting and methodology of Scope 3 attribution leaves a lot to be desired. In my view, oil and gas companies can do very little to impact consumer and business demand for their product. But this topic will be left for another post.

Methane is the area where I think not just Big Oil but the entire industry has been on its back foot and needs to figure out an industry-wide strategy to proactively address the issue. Many leading companies have made good-faith pledges to adhere to various global methane reduction initiatives. Frankly, it isn’t enough when raised to the industry level. It is an unforced error on the part of the oil & gas industry that there are any questions at all as to natural gas being the best transition fuel to get the world off of coal. This is especially true in 2021 where a combination of technology development and cost understanding has made methane a (mostly) fixable issue. Unlike so-called Scope 3 emissions which in my view are clearly driven by consumer/business choice, methane is unquestionably an industry issue.

The idea that China, India, and other developing countries can somehow switch all of their coal-fired power to renewables without utilizing natural gas is wholly not credible. I would give it a zero percent chance of happening within the next 30 years. Even if nuclear power plays a far more important role in the future, “methane free” natural gas is much needed. Frankly, natural gas will likely be used even if methane isn’t addressed. However, if companies/countries are going to claim to be “Paris aligned” and positive contributors to helping the world reduce its carbon/methane emissions, this is the place where the entire oil & gas industry can have the most meaningful positive impact.

The fact that methane leaks also occur in the agriculture and landfill industries is true but not relevant to what the oil & gas industry should do. It is a deflection, in my view, to not deal with this proactively irrespective of whatever is being done or not done in other industries.

Is there any role for Big Oil in new energy?

Yes, absolutely there is! As an important investor recently articulated to me (paraphrasing): “We are pragmatic about the ongoing need for oil and gas and would like companies to ‘future proof’ themselves in order to be prepared for a long-term transition.” There is nothing in this post that argues that Big Oil should not study, examine, and invest in energy transition strategies that make sense for a particular company. Rather, my point is that (1) forcing, demanding, or thinking there is some critical need for Big Oil to transition its CAPEX in order to accelerate energy transition is non-sensical ; (2) there is very little evidence in any sector of yesterday’s leaders being the key to tomorrow’s business; and (3) most Big Oils still need to improve legacy operations before being trusted with major investments in new areas.

Examples of companies taking some interesting energy transition steps include:

Valero Energy seems well positioned to excel in renewable diesel, which is a good fit for many traditional refiners and especially Valero, which has been involved in alternate fuels for over 12 years dating back to its 2009 acquisition of ethanol biofuels producer VeraSun.

Chevron, in my view, laid out a sensible approach to how it will be evaluating energy transition options over the next decade at its recent analyst meeting.

Occidental Petroleum’s CCUS strategy seems consistent with its legacy enhanced oil recovery business.

Equinor may be a good offshore wind company, building on its strengths as an offshore Norway oil and gas operator.

Hydrogen might be interesting within 30 years and it is not unreasonable for Big Oil to dedicate some R&D to this area.

The above list is not meant to be exhaustive. The point of this note is not to declare there is nothing for these companies to do. It is merely to suggest that the obsession by non-traditional investors and policy makers with what Big Oil is or is not doing is off-base.

We need sufficient oil and gas supply to match what people are demanding

The idea that you solve climate change by creating a shortage of traditional oil & gas supply, I predict, will be a big fail for the world economy, the climate, and especially for the least advantaged among us. It’s f---ing insane. Energy transitions are long-term in nature, measured in multiple decades that are more likely to round to a century than zero. DVD-to-streaming and landline-to-mobile happened fast. Energy will be massively slower. So Big Oil may not quite be ready to go the way of Blockbuster Video, Barnes & Noble, or Sears Roebuck.

If EVs and other low/zero carbon technologies ultimately diminish consumer demand for oil & gas sooner than I expect, Big/Medium Oil may well suffer if they are unprepared for that day. Why does anyone beside their shareholders, family, and friends care about their survival? Business failure and rebirth is a feature of capitalism—save polar bears, not Big Oil.

The Value Perspective podcast

This post was inspired by a discussion I had with Schroders value team portfolio managers on their podcast series The Value Perspective by Schroders. Please give it a listen (also available on iTunes, Spotify, or your favorite podcast player).

Personal note

Americans will celebrate the Thanksgiving holiday on Thursday. I will keep my thanks in this post business focused. I would like to thank all of you who are in my initial subscriber group, and in particular Subscriber #1: “Rob X”. I enjoy Twitter but wasn’t sure if I wanted to start (and therefore commit) to a long-form publication. With Twitter, I have felt no obligation to having any regular cadence and have at times gone long stretches without any tweet threads. As I was playing around with the Substack website, I linked it to my Twitter account, which to my surprise caused more people than I would have expected to sign-up. That initial burst of pre-publication subscribers motivated me to launch Super-Spiked last week. The act of writing has always helped me work through my own views; if others sign up and enjoy Super-Spiked, great; if not, I’m fine with an audience of one.

I am thankful for other Substack writers, in particular actual journalists (I am a former Wall Street analyst) who struck out on their own, leaving their mainstream media heritage. At a time of extreme polarization, mainstream media mis-information and chosen narratives, I am thankful for the modern age we live in that gives us choice on the voices we have access to and their freedom to publish. I would note that some of my favorite Substack writers have different opinions on a range of topics or are of a different political persuasion than myself. I love hearing their thoughtful, well-researched, well-argued views.

I am thankful for Substack.

Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Re “big oil” being successful in alt energy. Learned a long time ago, the way to make money is “do stuff you know how to do”. Anyone else remember Exxon’s foray into office equipment around 1980? How well did that work out? SLB buying Fairchild semiconductor? List goes on and on.

great piece Arjun! I look forward to reading future ones.