This week we take a look at worsening Middle East turmoil and what it could mean for the energy macro and energy equities. Prior to the recent round of hostilities between Israel and Iran, oil market observers had been bearishly biased due to the growing prospect for 2025 growth in non-OPEC supply to exceed growth in global oil demand. While handicapping the appropriate geopolitical risk premium is always a fraught exercise, it undoubtedly removes some amount of the ex-turmoil 12-month downside risk that market participants have otherwise been worried about.

Geopolitical risk premia has long been a feature of oil markets, and frankly is the core driver for our support of policies that maximize domestic oil production while also seeking to minimize domestic oil consumption relative to overall economic activity. Instead we have a non-trivial number of politicians and policy makers that seek to minimize domestic oil supply without taking substantive and effective steps to address the demand side of the equation (relative to economic activity), which is the precise opposite of what is needed to meet our hierarchy of energy needs: abundance, affordability, reliability, and geopolitical security.

For large population centers in the developing world that do not enjoy abundant domestic crude oil resources, geopolitical turmoil is an additional motivation to support demand diversification alternatives. That said, the sheer magnitude of unmet global energy needs points to growth in all forms of new and traditional energy for the foreseeable future as has long been our view.

Does the prospect for a broadening Middle East war change your commodity macro outlook?

Answer: No, not really.

We are in year three of emphasizing a “Super Vol,” rather than “super cycle,” commodity macro outlook (for oil, natural gas, and refined products), with geopolitical turmoil one of the core underpinnings of our view. We have long viewed geopolitical uncertainty from an “on/off” perspective. Over the past few weeks, oil markets moved from “off” back to “on” as the risks of direct confrontation between Israel and Iran grew. That said, oil prices are presently somewhere in the middle of what looks like a reasonable range—we are clearly not at a trough, but are also well below a realistic peak.

Right, but wouldn’t a regional conflict that potentially included major Middle East oil producers raise the odds of an oil “super-cycle”?

A: We don’t think so, at least not in the way we are thinking about it.

In our view, a 2004-2014-styled super-cycle is defined by surging oil demand, disappointing non-OPEC growth, limited OPEC spare capacity, and therefore the need to either price out demand (i.e., demand destruction pricing) and/or motivate the search for major new oilfields. We believe most of those variables do not exist at this moment, though we generally view OPEC spare capacity as more limited than what consensus believes.

OIL DEMAND: China oil demand headwinds and a generally lackluster global GDP backdrop suggests oil demand growth appears likely to be closer to 1 million b/d per year for 2024 and 2025, below the 1.5+ million b/d that would be consistent with a stronger super-cycle.

NON-OPEC & EXPLORATION: We believe that in a $65-$85/bbl WTI oil environment, non-OPEC supply can keep pace (and in 2025 likely exceed) circa 1 million b/d of global oil demand growth for the next several years. In our view, a new exploration cycle will likely be needed by the end of this decade. But for at least the next several years, a combination of rising oil production from US shale oil, Guyana, Brazil, and Canada can meet subdued oil demand growth.

OPEC SPARE CAPACITY:This is perhaps the one point where we are closer to oil bulls rather than oil bears. It has been our view for at least the last 25 years that OPEC spare capacity is routinely over-stated. We currently peg core OPEC spare capacity—which focuses on Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Kuwait, and Iran—as on the order of 4 million b/d (Exhibit 1). This is about 2 million b/d less than the 6 million b/d or so we think consensus assumes. Our methodology holds countries accountable for demonstrated production capability, as opposed to rhetorical self-reported capacity. We also ignore the vagaries of countries with routinely volatile production including the likes of Libya, Nigeria, and Venezuela.

Exhibit 1: We peg core OPEC spare capacity as on the order of 4 million b/d

Source: Energy Institute, IEA, Veriten.

OK, but there must be some level of disruption that would lead to an oil price “super-cycle”?

A: A big disruption would raise the odds of a very large, albeit temporary (lasting less than 12 months), price spike.

With above-ground inventories at generally low levels, we agree that a disruption that eliminated our estimate of core OPEC spare capacity would at a minimum boost the expected trading range of Brent oil from the $70-$90/bbl it has been stuck in, with short-term spikes (i.e., lasting less than 12 months) to levels significantly higher. However, we would still hold that a true multi-year, super-cycle would be driven by a combination of stronger oil demand growth and weaker non-OPEC supply.

When looking back at historic oil supply disruptions, the broader oil market context mattered. Disruptions were not automatically bullish, cyclically or secularly.

IRAN. As show in Exhibit 2, Iran has faced no less than 3 periods of disruption. The first was the most meaningful as it came with the Iranian Revolution followed closely by the 8-year war between Iraq and Iran. Between Iraq and Iran, a whopping 5+ million b/d of combined oil production was removed from oil markets. Notably, the 1980s marked a structural bear market for oil, punctuated by the 1986 crash. A multi-year period of negative global oil demand growth coupled with rising non-OPEC supply overwhelmed the Iranian and Iraqi production losses. Key conclusion: geopolitical disruptions are not automatically bullish events; the broader context oil markets are operating is critical to understand. The more recent disruptions in the 2010s were of course tied to US sanctions policy.

Exhibit 2: Iran oil production

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

IRAQ. For Iraq, we would observe that Gulf War 1 in the early 1990s led to a short-term bump to oil prices that ultimately gave way to a return to the lackluster oil price range that otherwise dominated the 1986-2000 period. Gulf War 2 was a very different story. Iraqi production did recover following the initial, most intense phase of hostilities, the end of which was marked by President Bush’s ill-advised “Mission Accomplished” photo op. At the time, oil bears predicted that by 2010-2012, Iraqi oil supply would reach as much as 8-12 million b/d. In reality, Iraqi oil supply did not even reach pre-war levels. Some 20 years later, we are still nowhere near 8-12 million b/d (Exhibit 3). The disappointment in Iraqi supply was one factor that did contribute to the Super-Spike era, which was a time of surging global GDP (China/BRICs expansion) and disappointing non-OPEC supply.

Exhibit 3: Iraq oil production

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

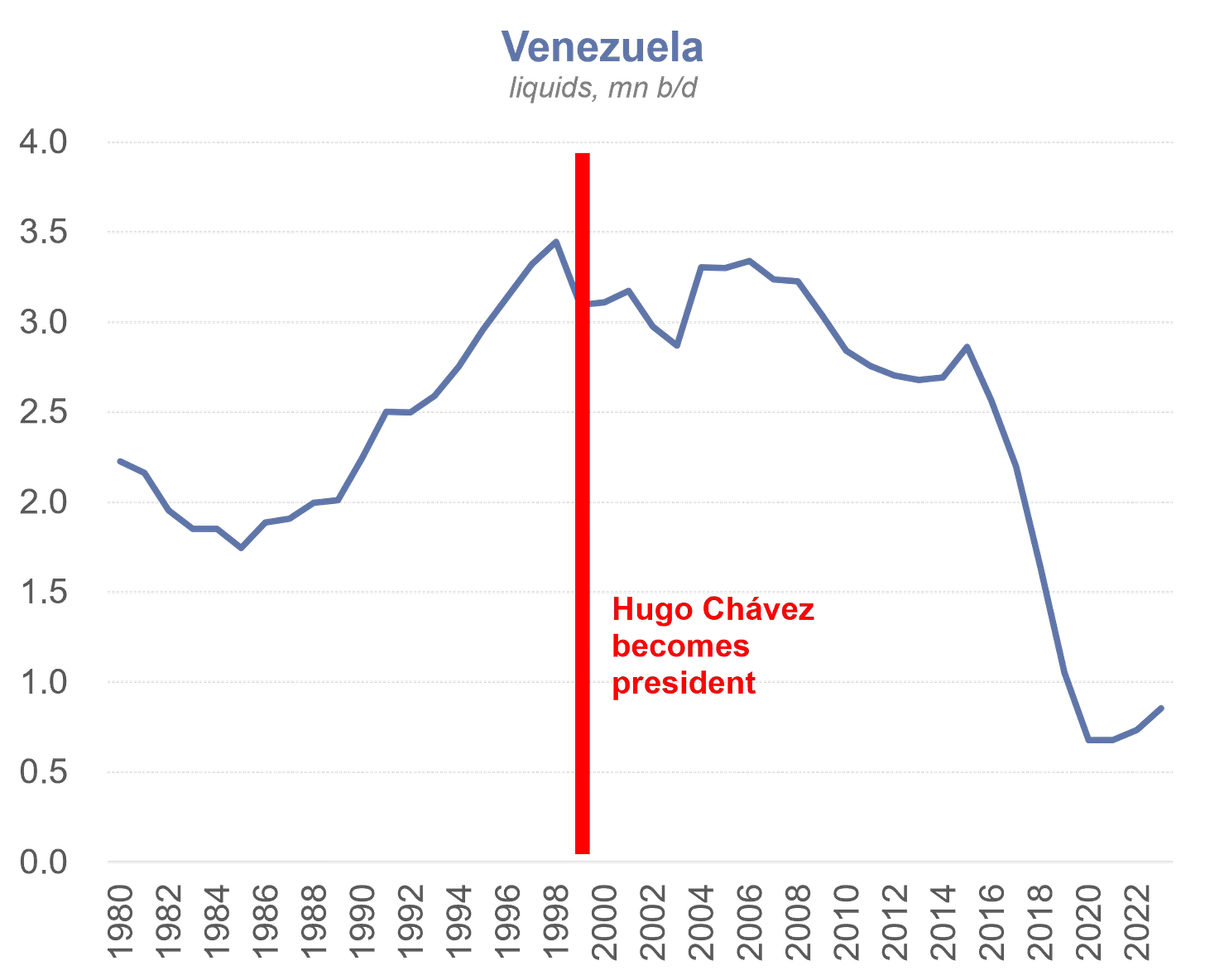

VENEZUELA. The long-term decline in Venezuela oil production following the ascension of President Hugo Chavez, which followed Venezuela’s oil growth miracle in the 1990s, coincided with the start of the Super Spike era (2004-2014) (Exhibit 4). We are not saying Venezuela’s problems were a major super-cycle driver. Rather, it was but one of a much larger number of variables that contributed to the quintupling of oil prices seen over this period.

Exhibit 4: Venezuela oil production

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

LIBYA. The ouster of Libyan leader in Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 led to a meaningful hit to Libyan oil production (Exhibit 5). Libyan shortfalls as well as turmoil in other producers helped mask emerging US shale oil growth, at least until that fateful Thanksgiving 2014 OPEC meeting that unceremoniously marked the end of the Super-Spike era. In this sense, Libya (and other countries) helped delay a more meaningful downturn in oil prices that came to pass over 2015-2020.

Exhibit 5: Libya oil production

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

What is upside geopolitical risk optionality worth?

A: It’s worth something.

There is at least some non-zero chance of a major disruption that eliminated core OPEC spare capacity occurring, such that some measure of a geopolitical risk premium that benefits oil prices and oil equities we think is warranted. To the extent investors have been more concerned about downside risks to oil prices due to pre-conflict bearish views on 2025 balances (i.e., non-OPEC growth expected to exceed growth in global oil demand in 2025), the sense that not all risk is skewed to the should boost, or at least prove supportive to, traditional energy equity valuations.

Will Middle East turmoil serve as a reminder of the importance of US, Canadian, and Norwegian oil production?

A: Yes, for politicians and policy makers that live in reality.

It would seem obvious that citizens of the United States, Canada, Europe, and their allies are relatively more secure when the oil industries in the US, Canada, and the North Sea are thriving. Still, there is a non-trivial contingent of politicians and policy makers in those regions that think otherwise. The view that curtailing domestic production somehow raises the odds of so-called climate ambitions being met is demonstrably false. The (potential) absence of domestic oil supply would simply mean increased reliance on producers in the Middle East and Russia and greater risk of economic disruption from geopolitical turmoil tied to those countries. We are a long way from the lived experience of the 1970s. Let’s keep it that way!

For those focused on “the path to net zero,” it is our view that such an objective will never be met—certainly not in the next 25 years let alone 75 years—via “keep-it-in-the-ground” domestic oil and gas supply and infrastructure policies. As we have begun to articulate, new frameworks and perspectives on how to meet economic and environmental goals are needed. The starting point begins and ends with first solving for how everyone on Earth becomes energy rich; the process of meeting that objective invariably will lead to non-oil technologies in particular being discovered and commercialized—a key point under-appreciated by those most focused on addressing climate concerns.

How does Middle East turmoil impact future oil demand?

A: We see it as long-term bearish.

It has been our view that as the major billion-person regions move up the economic and hence energy demand “s-curves,” they will be highly motivated to find ways to limit exposure to imported energy, most notably crude oil. Geopolitical turmoil will only serve to reinforce that impetus.

Using India as an example, we see a total addressable market (TAM) for oil of 45 million b/d versus just over 5.5 million b/d of current consumption, which equates to 10 barrels per person per year. However, with only 0.5 million b/d of domestic oil supply, we see little chance India would want to come anywhere near 44.5 million b/d of implied oil imports. EVs (electric vehicles) and LNG (liquefied natural gas) trucks are part of the answer to lowering its oil TAM while still achieving rich country status. However, with India currently using just 1.4 barrels of oil per person per year, it is likely to be firmly in the “all of the above” category for the foreseeable future, meaning oil, gasoline, EVs, petroleum diesel, LNG trucks, pet chem, and jet fuel will all see substantial growth.

There is not a country on Earth that wishes to be anything other than rich and self-sufficient in energy; it is the lifeblood for all economic activity and human flourishing. A major positive of many of the newer forms of energy is that once up and running, they are de facto domestic energy sources. Solar is a great example of this. Solar panels might be imported from problematic areas engaged in human rights violations, but once installed the ongoing flow of energy is domestically sourced (i.e., from the sun).

Turmoil in the Middle East and with Russia simply adds to the urgency of billion person countries to diversify away from imported energy. That said, for the climate conscious, domestic coal is likely to be a major energy source for India and other developing countries as it has been (and still is) for China.

What other energy areas benefit from Middle East turmoil?

A: Power!

Power generation, which is already thought to be a winner due to aging grids, data center growth, and a general electrification trend (e.g., EV growth), can add another positive driver to its list. Electricity is inherently a domestic endeavor, even if in smaller countries there can be cross border flows analogous to interstate transmission in the United States. Key sources of power generation include nuclear, solar, wind, natural gas, and coal, with longer-term potential in geothermal. All are likely to grow significantly in coming years and decades as electrification is a key theme to making everyone on Earth energy rich and being able to do so without an over-dependence on imported energy.

⚡️On A Personal Note: My First Trip to the Gulf and Work-Life Non-Balance

My fist ever trip to the Middle East was in May 2006. I had been invited by the Chief Economist of the National Bank of Kuwait (NBK) to discuss our “Super-Spike” call. Our focus was then, as it is now, on the long-term outlook for oil and energy markets. The three other external speakers on the panel were knee deep in the short-term supply/demand dynamics that most everyone else obsesses over. I never had much interest in day trading and remember thinking they are all missing the bigger picture.

At the time, my wife was 8 months pregnant with our baby (child #3). Memories of 9/11 were still fresh for those of us living in the greater New York City area, and she was unquestionably not excited about my making this trip. I remember delaying my trip out by 1 day due to a false alarm that the baby was coming. 2006 turned out to be my partner year (announcements are made in October in even-numbered years). Staying home with a very pregnant wife plus 2 others under the age of 5 at the time versus doing whatever it would take to be a leading oil equity analyst and a future Goldman partner? In those days, Goldman won. I have no regrets and I believe my wife would agree.

As a managing director and then a partner, I was often asked by my superiors to make “work-life balance” speeches when addressing my business unit and eventually the broader research department. My view at the time was and still is (1) the opportunity to work at Goldman was an incredible privilege; (2) if you wanted to work “part-time” you could go to any of our “peers” or worse, a foreign bank trying to break into US markets; (3) unless you were in the hospital, you should be working; and (4) once you retired or otherwise left Goldman Sachs, you could focus on the “life” part of work-life balance. I don’t know if this philosophy still exists at Goldman. I do hope that my kids will find careers or life paths that they are similarly passionate about. Unfortunately, they were raised in a more affluent setting than my wife or I were. Sorry about that kids. We hope it won’t hinder your future career success.

A 2012 note from the baby my wife was pregnant with in 2006: Credit to her at age 6 for already understanding that “work-life” balance meant finishing work before Father’s Day pancakes!

Source: Super-Spiked

My travel companion on that first Middle East trip was Goldman’s one and only Chukri Moubarak. My wife, like everyone who has ever met him, was a Chukri fan. His presence gave her comfort that I would be fine traveling to the region. Ironically, it was Chukri, who grew up in Kuwait City, that was regularly hassled by the customs guards. My American passport and Indian heritage were not a problem and I sailed through customs both in and out of Kuwait City and Doha, Qatar. Chukri being a Lebanese Christian by background apparently was an issue with those reviewing his papers and passport. The Middle East has a lot going on that most Americans, including me, have little real awareness.

After Kuwait City, we went on to Doha. We hired a driver to take us to Ras Laffan Industrial City, the heart of Qatar’s LNG business. Chukri charmed his way through the gate to meet a contact he barely knew but who generously and graciously gave us a tour of the area. Ras Laffan remains my favorite industrial city anywhere in the world. It is a truly remarkable place that to me is unrivaled anywhere else. I do remember wondering what kind of life the bus load after bus load after bus load of immigrant workers had…probably longer hours and more challenging working conditions than being an equity research analyst or junior banker at Goldman. At least no one was making them sit through “work-life balance” hypocrisy.

The trip back to Doha was the first and thus far only sandstorm I’ve ever been in. The driver had to have been going 100 miles per hour on what I remember being a 2-lane bi-directional road. Visibility was zero. There is no way we would have survived a head on collision. Chukri and I basically sat in the backseat and prayed for a good outcome…which we got. We celebrated life by getting a McArabia burger, fries and a vanilla shake at the McDonalds that you come upon when returning to Doha. Best Mickie D’s ever!

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

The bottom line is the Oil Industry has become a victim of their own success and that will continue to improve and grow as they utilize A I , although I don’t know how you can improve on drilling a 3 mile lateral and hitting a shoebox . One of the major domestic constraints for oil and gas is the cost to comply with the massive amount of new regulations ( costs Increase )and the difficulty to build infrastructure in a timely manner if ever . The A I boys now have those issues you run everyone’s electric bill up see how the public reacts to that and putting a mini nuke next door or even a turbine not in my back yard !

Always interesting to hear the stories about travel and the personalities and characters in the energy business. Sometimes meeting someone in person on their home turf can change your thinking in a way that no amount of spreadsheets ever can. Definitely we Westerners usually lack a good understanding of the Middle East, a good source I listen to is Dr. Anas Al Hajji, I've learned a lot about the Saudi perspective on energy markets from him (including the shift to other uses of petroleum in response to the strong messaging from the Western world about peak demand, whether that prediction peak demand pans out or not, it has not gone unnoticed by the Gulf producers). 'Out of the Desert' by Ali Al-Naimi is also a classic, well worth reading and re-reading every few years.

https://www.amazon.ca/Out-Desert-Journey-Nomadic-Bedouin/dp/0241279259