FAQ: Peak demand? Peak Permian? What About Africa?

Q&A and Clarifications

This week we return to a Q&A-styled note to address questions we have received, grouped by Super-Spiked theme.

NAVIGATING THE ENERGY CRISIS ERA

Question: Isn't the peaking of oil demand inevitable?

It is now well documented that the energy sector is still trying to shake off memories of last decade's poor profitability and the resulting diminution of investor interest and appetite for new CAPEX. We recognize that the period of structurally improved ROCE has not yet been long enough to give investors confidence the 2020s will not be a repeat of the 2010s. The other big overhang on the sector has been broad-based calls from leading Western institutions that have forecast a near-term peak/plateau/decline in oil demand.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) infamous May 2021 Net Zero By 2050 report showed a scenario where global oil demand peaked in 2019, pre-COVID. Other macro forecasters have expected oil demand to peak somewhere in the mid-2020s. It is noteworthy that despite a generally choppy global GDP environment—particularly in the largest oil consuming regions of China, Europe, and the United States—global oil demand is on-track to obliterate the doom-sayers.

In a recent report that looks at medium-term (next 5 years) trends, the IEA now expects oil demand to grow at least until 2028 (the last year shown in the report), a far cry from the 2019 peak shown just two years ago. Yes, different groups produce the various reports. And yes, "Net Zero by 2050" was a scenario not a forecast. But perhaps no report has been more weaponized by "climate only" politicians, academics, and activists than the Net Zero by 2050 report declaring no new oil and gas fields would be needed in order to meet the IEA’s net zero by 2050 scenario.

It's too strong to call this blatant misinformation. Forecasting and scenario analysis is tough business. We can speak from personal experience having made many wrong calls of our own. It is the weaponization of that report, hardly a shocking development, we are calling out. We were never on-track for that scenario of a 2019 peak in oil demand or circa 75 mn b/d of oil demand in 2030. In fact, the IEA's more recent "Oil 2023" report now calls for 105 mn b/d of oil demand in 2028, a remarkable 40% higher than its "Net Zero by 2050" advocacy (Exhibits 1 and 2).

The notion that oil and gas is a sunset industry has weighed on investor sentiment. In the same way it's not clear how many years of competitive profitability are needed to regain investor trust, it's not clear how many years of rising oil and gas (and coal) demand will be needed before investors recognize traditional energy will have a dominant role to play if we are to ever move to a healthier energy evolution.

So, no, we do not believe the peaking of oil demand is inevitable, either this decade or next. Is it possible next decade? Perhaps. But no one should think it is a foregone conclusion.

Exhibit 1: IEA’s “Net Zero by 2050” global oil and natural gas demand scenario

Source: IEA

Exhibit 2: IEA’s latest “Oil 2023” outlook

Source: IEA

Q: Won't technology extend the duration of rising Permian supply well beyond the next few years?

The Permian Basin has proven to be the gift that keeps giving looking back over a century. Shale is only the most recent of advancements in the Permian. As remarkable as shale growth has been over the past decade, recovery rates of original oil in place are still very low, suggesting meaningful long-term upside exists as technology unlocks overlooked resource.

That said, it is our experience that technology gains come in waves, with extended periods where near-term supply growth matures and can be flat or decline for many years. Often it takes a combination of a major oil price and CAPEX cycle to motivate the unlocking of next generation technology. Right now, we have a volatile oil price environment and only modest CAPEX increases. As such, when thinking about the next decade of oil supply potential, our base case expectation is for Permian Basin supply growth to slow appreciably over the next few years and reach plateau within a 2026-2028-ish time frame. Unlike some, we do not expect Permian supply to enter long-term decline this decade (cyclical decline due to oil price driven rig count reductions is always possible).

Q: Are you sure we need a major new CAPEX cycle?

There is a common, long-standing bear call on oil where an attempt is made to add up known sources of supply growth and conclude it exceeds likely oil demand growth. This in fact was the original mistake we made in 2002 and 2003 in concluding non-OPEC supply would grow 3%-5% per annum in coming years, well in excess of forecasted demand growth of 1%-2% per annum at the time. With hindsight, both parts of the forecast missed: demand exceeded projections, in particular after oil prices rose sharply, and supply lagged expectations badly, even as it grew in absolute terms to meet ultimate demand growth. Most notably, higher prices coincided with positive demand surprises and negative supply growth relative to expectations during the Super-Spike era of 2002-2014.

The fact that oil demand is likely to at least modestly grow in coming years rather than plateau and decline as some have predicted is noteworthy. The fact that US shale oil supply accounted for around 70% of global oil supply growth last decade (pre-COVID) and is now on-track to slow meaningfully is also noteworthy. We haven't even started the process of trying to figure out what comes next after shale. Last time it took a decade and a quintupling of oil prices to realize US shale was the answer.

Everyone is assuming the oil industry is entering its sunset phase. Risk/reward suggests meaningful opportunity exists in the event that is either not accurate or, at worse, way premature.

CORPORATE STRATEGY

Q: If shale is maturing, who will be best at adapting to whatever the future holds?

It is not easy for companies to change skillsets or areas of focus. It is, however, a common feature of all companies that have withstood the test of time. The best examples of companies that have consistently evolved and succeeded are the Super Majors, on both sides of the Atlantic. My usual example is to highlight ExxonMobil and Shell's dominance from 1910-2010. That example extends to Chevron, BP, and Total as well. Over one hundred years of history, through world wars, regional conflict, nationalizations, openings, and numerous plays coming in and out of favor, the Super Majors and their predecessor companies have remained dominant players within energy, generally at the high end of industry profitability, and typically major weightings in important investor benchmarks (e.g., S&P 500, FTSE).

Among E&Ps, one company that jumps out to me within my career is EOG Resources. At the Goldman Sachs Energy Conference in Miami in the early 2010s, CEO Mark Papa declared that shale gas was over, shale oil was the future, and that EOG would be making a whole-sale change to its strategy and portfolio accordingly. While I don't remember the exact year (2010-2012), it was a remarkable declaration that proved correct. EOG is hardly alone among E&Ps, but the example was long enough ago and Mr. Papa is retired that I think I can stay out of trouble by including just that one. (Note: between all of my various affiliations including Veriten and others, I have had a policy to not talk about specific current companies. I am viewing this as a historical example not a current view on EOG.)

Among refiners, we have seen many evolutions over my 30-year career. From the advent of CARB (California) gasoline to strategies that emphasized heavy oil coking operations as Venezuela supply ramped to most recently the shift to Mid-Continent US, light-sweet crude oil discounts as shale ramped. For a high fixed-cost business, independent US refiners have been remarkably adaptable as a sector.

Q: Won't all SMID-CAP E&Ps ultimately need to merge with or sell to larger entities?

In a world where two of the most recent transactions involved Super Majors purchasing SMID-CAP E&Ps for essentially no meaningful share price premium, the inevitability of E&P M&A has taken on new meaning. Size and scale and the often better valuations that come along with being bigger point to additional transaction activity. But the absence of meaningful takeout premiums suggests investors will need to figure out which combinations will actually make for better companies over the long run rather than just hoping for a short-term share price pop.

We can't recall a time in our career where SMID-cap E&Ps sold to Super Majors without requiring a large premium. Times have changed. The ultimate goal is still the same: for the merged entity to improve the duration by which it can generate advantaged returns, through-cycle free cash flow, and grow long-term shareholder distributions.

Q: At what pace should traditional energy grow low-carbon businesses?

Over 2020-2022, we were highly skeptical of the aggressive steps many European Super Majors were taking to transition to "new energies" and away from traditional energy. We preferred the go-slow approach seen by the US sector. Over the past year or so, we have seen the Euro Majors adjust back in the direction of continuing traditional energy investment. At the same time, US Majors have continued to selectively ease into low-carbon opportunities via acquisition (e.g., CVX-REGI, XOM-DEN).

In our view, the overwhelming objective of traditional energy companies should be to profitability produce the oil and gas the world continues to demand. Full stop. A healthy western oil and gas industry (USA + Canada + Europe) is a critical counterbalance to national oil companies that dominate other parts of the world.

In order to meet the energy needs of the other 7 billion people on Earth that use a fraction of the energy on a per capita basis versus the lucky 1 billion of us that live in the United States, Western Europe, Canada, Japan, and Australia/New Zealand, we will need all forms of energy. Off a low base, many low-carbon energy technologies will experience substantial growth in the coming decades. It is logical for the Majors and other traditional energy companies to evaluate expansion opportunities that are consistent with skillsets and capabilities they hold. But it is not and should not be mandatory to go into new, low-carbon areas.

GEOPOLITICS

Q: What future country opening would be most exciting but could impact the oil macro view?

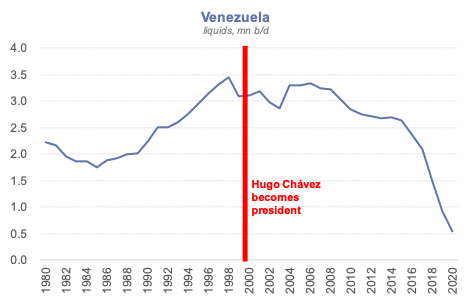

Venezuela! We know what you are thinking. Venezuela has been a disaster since the late President Hugo Chavez gained power in the early 2000s. The 1990s were different. A (then) re-opening to western majors drove meaningful production growth and profitability via development of Venezuela's Orinoco Belt (Exhibit 3). US majors were well positioned to help with upstream development and the corresponding upgrader needed to process the heavy oil. Orinoco Belt production was then shipped to US Gulf Coast refiners, a win-win for the USA and Venezuela. Original fiscal terms on these projects were favorable and quite profitable for western majors. The country benefited from a major investment cycle.

We are obviously a long way away from this golden energy era in Venezuela. But it has now been over 20 years of a straight line down for the country. My recollection is Venezuela's heavy oil cold flows (i.e., the reservoir does not need to be heated) several thousand b/d per well. It is the greatest heavy oil in the world. As shale slows, we will need new sources of global supply and there is no reason Venezuela should not be a part of it. They just need a government that moves in a pro-capitalism direction. Venezuela is but one example for why our Twitter tagline includes the "pro capitalism, anti socialism" motto.

There are of course many other countries with interesting oil and gas resource potential that could or should open to foreign investment. Nigeria used to be a focus country of the Super Majors. Brazil has of course garnered interest. North Africa and other countries in West Africa have seen interest. The list of potential areas is long. But all require host governments to want to welcome back foreign investment via reasonable fiscal and contract terms.

Exhibit 3: Venezuela oil production once boomed but is now in an extended bust phase

Source: IEA

ESG 2.0

Q: Isn't your bullish view of Canada's oil sands at odds with Sustainability investing?

We cannot think of a traditional energy region more compatible with Sustainable investing than Canada's oil sands region, the opposition to which we find completely baffling. Key Sustainability attributes of Canadian steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) oil sands projects include:

Competitive long-term profitability.

Long-lived, free cash generation after initial CAPEX.

Minimal ongoing spending or activity to maintain production.

Limited above-ground disturbance relative to volumes produced.

Credible plan to eliminate Scope 1 emissions, which is the one environmental attribute where Canada’s oil sands have historically compared less favorably to other crude oil sources.

Located in a country that allows immigration of refugees and others from less developed nations.

Located in a country that actively promote the values Sustainability investors tout, including areas like gender diversity and LGBTQ rights. The same cannot be said for many other energy producing regions.

ENERGY TRANSITION NEEDS TO TRANSITION

Q: Shouldn't Africans have the opportunity to demand a 2nd barrel of oil? How about a third barrel?

Unsustainable numbers that don't make sense:

1.3 billion Africans use about 4 million b/d of crude oil or just over 1 barrel per person per year. By way of comparison, around 375 million US and Canadian citizens consume 23 million b/d, or over 20 barrels per capita.

African countries collectively produce about 7 million b/d, resulting in net exports of around 3 million b/d to the Rest of the World.

The USA plus Canada have combined oil (liquids) supply and demand of 23 million b/d. Our exports to the Rest of the World net to zero.

A continent that uses around 1 barrel per person per year is actually providing oil for the Rest of the World, which currently consume far more oil than does the average African.

The richest region in the world, the United States plus Canada, exports net zero oil to the Rest of the World and is facing intense pressure to actually produce less from left-of-center politicians and activists.

USA consumers shift toward circa 70% SUVs/30% light cars from the opposite 30 years ago. This wipes out the majority of government-mandated fuel economy gains.

Primarily European institutions and climate activists aggressively seek to stop a singular oil pipeline from Uganda to Tanzania located within a continent using 1 barrel of oil per capita.

Seriously, what the heck? The energy transition as currently being attempted is devoid of economic and social justice for the least fortunate in Africa.

There is significant scope for African nations to improve economic outcomes and living standards for their citizens. Improving to a measly 3 barrels of oil usage per capita would net 8 million b/d of oil demand growth in Africa. The pace at which that happens versus possible OECD declines is effectively the energy transition. In our view, Africa will ultimately be at the heart of whether the world is successful in meeting all of its objectives, which I will simplistically narrow to gross zero energy poverty coupled with improved environmental standards.

⚡️On a Personal Note: Best hire ever

On a recent Goldman Sachs webinar, I declared Neil Mehta "my best hire ever." This is a true statement, but bears further explanation. As some of you that are investor or corporate clients of Neil (or Goldman Sachs) can attest, he is a rock star energy analyst. If I keep the perspective focused on the Energy sector and not my broader Director of Research role, Neil rose from a junior analyst to head of Goldman's Americas Energy Equity Research team. He stayed at Goldman as he rose through the ranks, now has a prominent role, and is outperforming doing it.

As a covering analyst, I was blessed to have had many great junior analysts, both directly on my team and within the Americas Energy business unit. It has always been a team effort. I held my juniors to high standards and they delivered. Work-life balance in those days meant you dedicated your life to working at Goldman and could enjoy life after you retired or left the firm for an easier, less demanding job. I was not devoid of disaster hires, but the firm has a good process to quickly weed out those for whom Goldman is not a good fit.

Our Americas Energy team spanned the world, including New York, Houston, Salt Lake City, Sao Paolo (Brazil), and Bangalore (India). Super-Spiked would not be a thing without their efforts, contributions, blood, sweat, and tears. And I am not referring to one of my disaster hires who left a performance review literally crying...that's for another story. I am grateful and proud to have worked with so many great formerly junior analysts, most of whom have moved on to significant career success elsewhere. Neil Mehta is one who stayed at Goldman and succeeded; he is my best hire ever.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

I am pleased to see you now use the phrase “move to a healthier energy evolution” rather than referring to an “energy transition” since there is no known available energy source to transition to. I do have a further question: What if there is no “healthier” energy evolution? What if those calling for reduction in CO2 emissions based on the supposition that CO2 is bad for the environment as though it is a given that it is some form of pollution, what if they are wrong? Just suppose CO2 emissions - not particulates or other foreign matter, but CO2 itself; the gas plants breathe - are not bad at all - what then? What if it turns out that CO2 is actually good for the planet? It may be viewed as heresy, but has anyone asked that question and what it would imply? It doesn’t necessarily mean other forms of energy cannot be examined and pursued if they make sense for economic and other reasons, but it would meaningfully change the direction and priorities if it were no longer taken as a given that CO2 emissions were viewed as “pollutants” to be minimized at all costs.

Arjun, you've written before about how countries with domestic coal supplies will use that resource to ensure their energy security. In his substack note yesterday, David Hay was commenting that China's EV push together with usage of coal to power electrical generation is a way to reduce dependence on oil. I've heard others like Michael Kao make a similar point. Won't such energy security based strategies, particularly for large oil users like China and India, eventually impact the global demand for oil?