FAQ: Resilient Coal, Cost of Capital, and ESG 2.0

Q&A and Clarifications

Four written posts, two videopods, and several webinar and podcast appearances to start 2023 have apparently created more questions than I have succeeded in answering. Lets get right to it with a Q&A on nine burning questions within the themes of resilient coal, cost of capital, and ESG 2.0.

Resilient Coal

(1) Given China’s current CO2 emissions are more than the US and Europe combined and it continues to grow coal output, why should the US waste effort on energy transition?

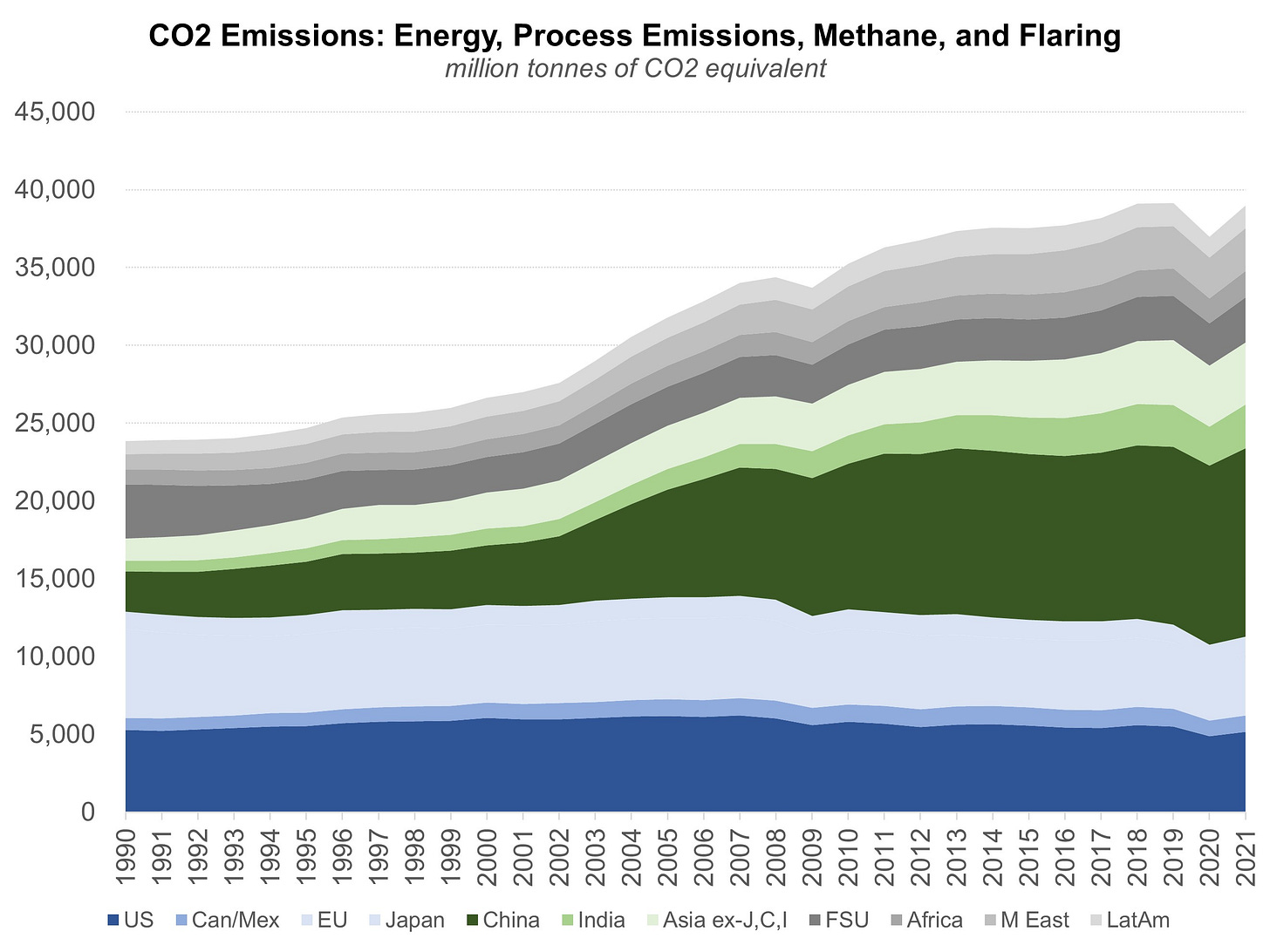

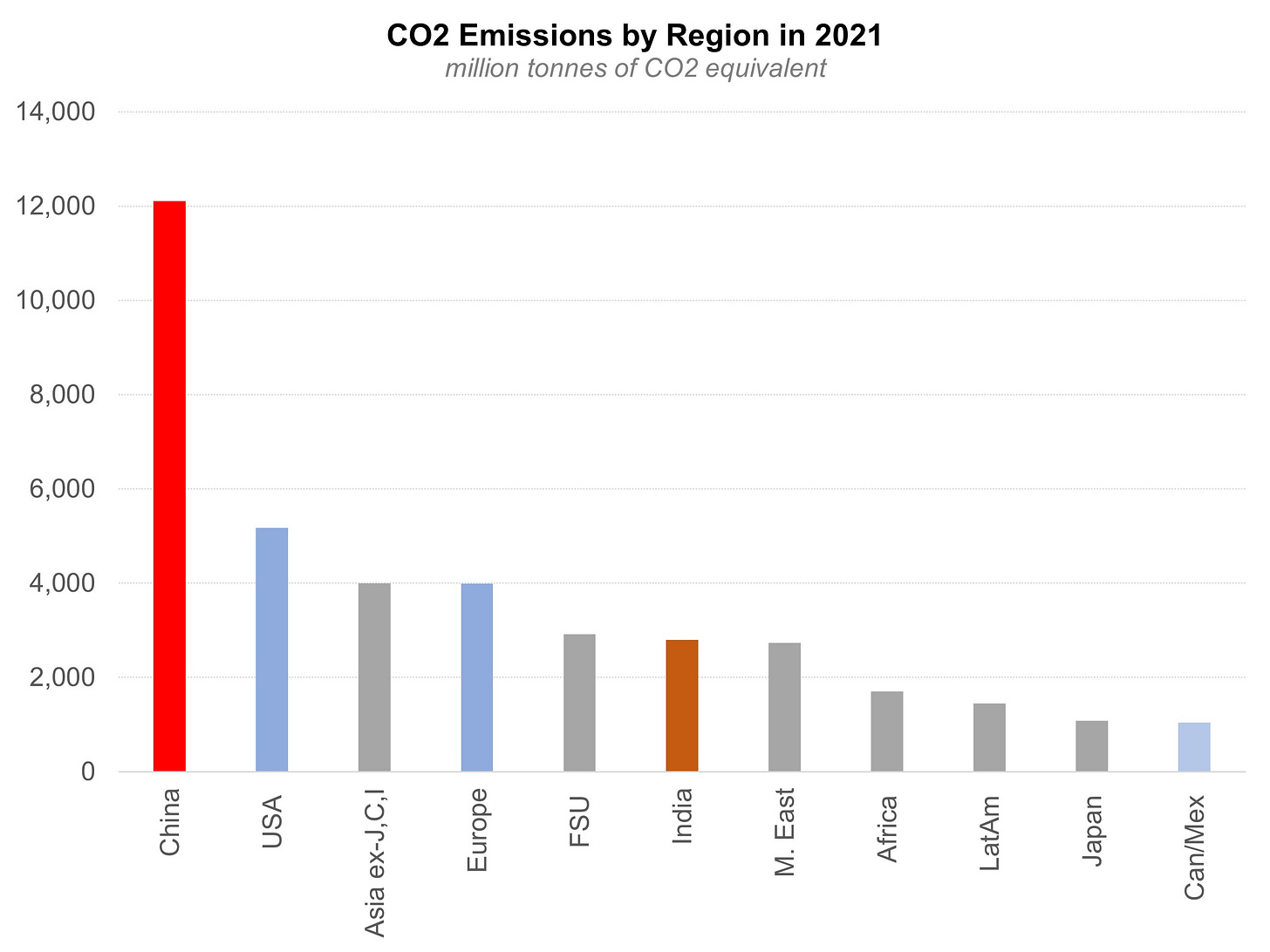

This question captures some of the mainstream opposition to more meaningfully making carbon reduction a part of US energy and economic policy: Does it even matter when you look at current and expected CO2 flows from China, India, and other developing economies vis-a-vis current US emissions, which are already in decline (Exhibits 1-3)?

Exhibit 1: The future trajectory of global CO2 emissions is overwhelmingly driven by the outlook for China and other developing areas

Exhibit 2: China’s current CO2 emissions about equal the USA and Europe combined

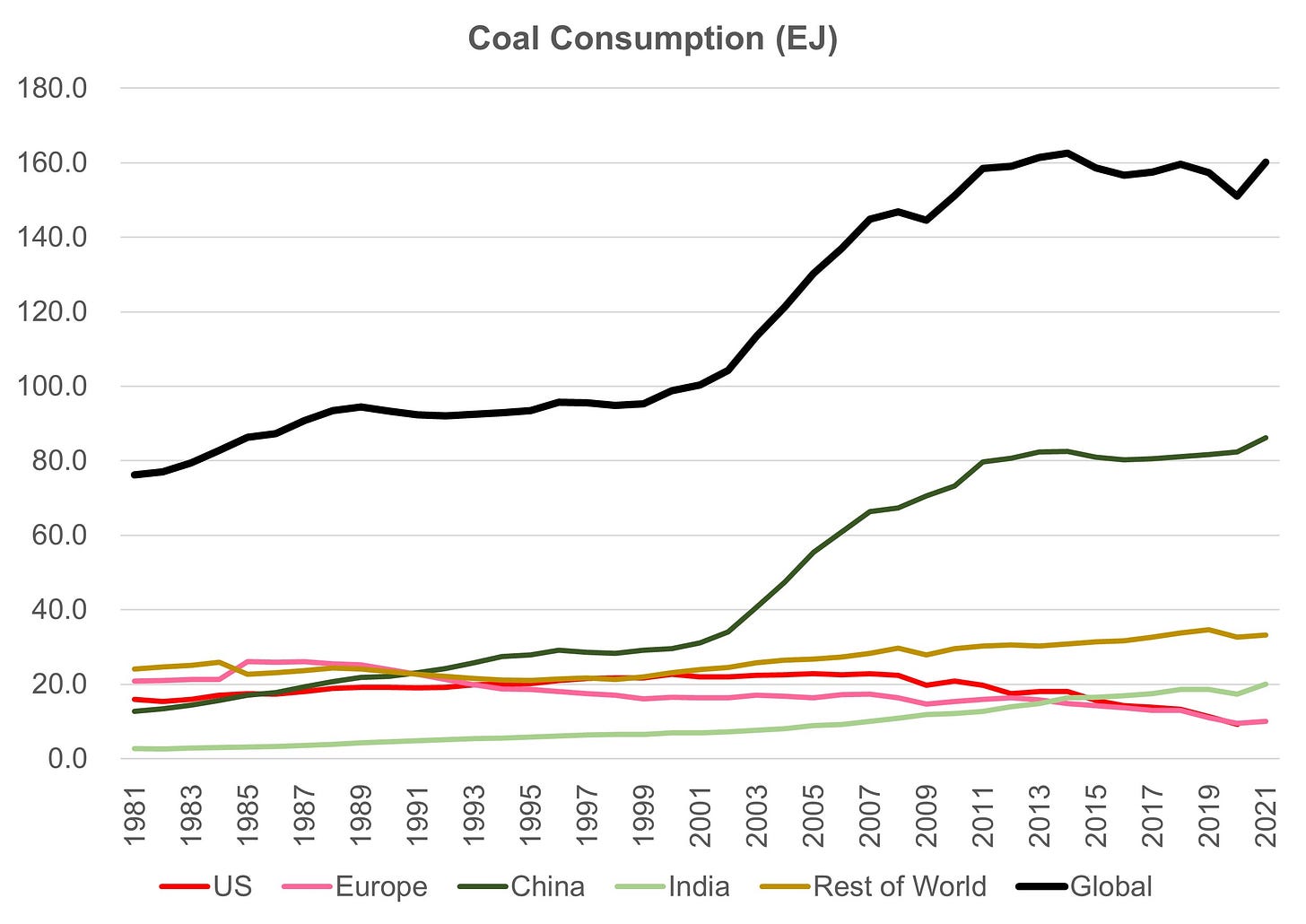

Exhibit 3: Global coal consumption is at all-time highs driven by growth in China, which shows no signs of rolling over

Why should the USA strive for climate solutions when China is still going in the direction of higher emissions and other developing areas will having growing emissions as well?

In my view, the US (and Canada) will be economic and environmentally stronger with a combination of higher oil and gas production AND lower oil product demand relative to GDP. While the oil intensity of our economy has been in structural decline for decades, there is still the opportunity to further de-link oil product demand from economic growth.

Improving the multiplier of GDP to energy usage improves affordability, reliability, and security, while also helping with environmental and climate objectives.

Diversifying the nature of our energy demand (e.g., EVs, heat pumps, renewables) can free up crude oil, natural gas, and coal for export to the rest of world, which enhances our geopolitical security and relative economic advantage. It also helps make the rest of the world richer by providing reliable and much needed supply from a region with strict environmental regulations and labor standards.

If a so-called “just transition” is a goal, there may not be anything more just than freeing up American and Canadian oil and gas resources for developing economies that are allied with the United States and Canada.

If over the past 20 years we had actually achieved 90% of our CAFE standards, rather than missing the targets by circa 75% due to the SUV-ification of our auto fleet, gasoline demand would be 1.4 mn b/d, or 16%, lower today by my estimate. If we were to not make excuses for heavier vehicles, an issue being replicated with EV subsidies, a further meaningful dent in gasoline demand would be possible. Growing electrification could then be done at a modest pace consistent with a reasonable expansion of the battery and materials supply chain and without forcing "100%" adoption which is both unjust and likely uneconomic.

The combination of healthy economic growth, fully de-linking oil product demand from GDP growth, and increasing oil and gas supply exports, in my view, should be our national objective. In the case of China, we should not be OK with importing goods and products made from supply chains with higher-carbon intensity and worse environmental and labor standards. How does that make any sense?

(2) Since Americans won't (and some say shouldn't) sacrifice a comfortable lifestyle, shouldn’t we give up on any the hope of moderating our demand for fossil fuels?

Let me try to answer this with an example. Let’s say you live in an American suburb and your streets are over run with parents hauling small children in Lincoln Navigators or Chevy Suburbans. Is this the great lifestyle we are trying to defend? Traffic is terrible. Parking is a nightmare. Being run down by tank-like vehicles while walking your golden doodle is a real risk many American bravely face every day (Exhibit 4). Air pollution is worse than it could be. What is “comfortable” about any of that?

Is there no scope to incorporate sustainability into our cities and suburbs? There is plenty we can do that does not involve sacrificing our lifestyle but would improve air quality, quality of living, and potentially lower the carbon intensity of our economy.

Exhibit 4: Suburban dog stages sit-in protest against poor mpg, unnecessarily large family SUV…a tense situation was peacefully defused with treats and promised walk around the block

(3) If solar & wind are so cheap, why did China add so much coal generation especially since China is a major solar panel manufacturer? And why is it still adding coal generation?

Coal generation expanded substantially over the past 20 years fully coinciding with China’s economic miracle. The relationship is 1:1. If you want to be a rich country and not remain a poor country, the pathway has been via the use of coal and crude oil. While the cost of solar generation has decreased substantially over the years, it is not a dispatchable fuel and when you include the cost of storage, it has clearly not been competitive with coal in China (or anywhere). Coal checks ALL the boxes: abundant, affordable, reliable, and secure. Counting CO2 is a luxury good that has yet to be prioritized over other drivers outside of elite circles or wealthy nations. You can agree or disagree with that last statement; I offer it as a factual observation.

I think some of you will appreciate the irony that solar panels are actually manufactured in China. Yet, China basically used a massive increase in coal to fuel its move out of poverty to being a global economic power. None of that should be a surprise. This point of this post is in part that we need to stop pretending it’s not on track to continue in China and to recognize its quite likely to be repeated in India and other developing nations.

Cost of Capital

(4) Isn’t the circa 25% ROCE achieved in 2025 "peak of cycle" and as good as it will get? Does it ever make sense to invest in cyclical sectors when “over earning”?

I was asked a version of this question on the recent Evercore ISI fireside webinar I did with James West and Steve Richardson last week. It's a great question. I agree that there is risk that 2023 ROCE could be lower if the macro backdrop turns out to be less favorable than 2022. However, in my view, there is no chance that a track record of zero ROCE over 2011-2020, 10% in 2021, and a singular great year of circa 25% ROCE in 2022 marks the top or end of the cycle.

I have been describing the commodity backdrop as Super Vol. When I add up the periods of high/medium/low ROCE over the coming decade, I get to an expected favorable result versus what investors appear to be assuming today in energy equity valuations. For those that did not enter the sector in 2020 or 2021, the question is when to enter (or re-enter or add). Since Super-Spiked is not an investment newsletter, I’ll leave short-term trading calls to others.

Rather my point is that any investor I would think should run different cash flow scenarios for 2023-2030 and then various terminal cash flow scenarios (modest growth, plateau, slight decline, fast decline as examples). Add it up. Invest when your discount rate is exceeded by the IRR of probability-weighted free cash generation.

(5) Since rising capital intensity is usually frowned upon, should companies not bother raising CAPEX?

I fully acknowledge investors in general do not like CAPEX increases and for good reason. But oil and gas reserves naturally deplete and the only way to extend the runway is to spend capital. In the same way many investors aspire to be contrarian, counter-cyclical investing in the oil and gas business means spending when overall CAPEX is still low and not spending when it is high or after we have had many, many years of favorable profitability (which is not the case today…we have had a singular great year).

I will guess the biggest uncertainty is related to so-called mega projects with multi-year upfront CAPEX requirements before cash flow is generated. But unlike short-cycle projects, the ensuing free cash flow can last for decadal-type time frames, supporting free cash flow and dividends for much longer periods of time than short-cycle spending. Investors are gong to have to assess whether they have confidence in a management teams’s ability to execute on mega projects.

(6) The 1H2023 looks like it could be a tougher period for traditional energy given the residual effect of a warm winter and a potential Fed pivot, which might favor “growth” sectors that lagged in 2022, no?

We shall see. Who knows. Short-term macro guessing I do not find super interesting, and mercifully, no one is paying me anymore to do it.

Underpinning my Super Vol framework is the idea that with limited spare capacity, generally low inventory levels, and CAPEX that is still closer to trough than peak, whenever economic growth does attempt to move back toward trend, energy commodity tightness will re-emerge. The global economy simply can NOT sustainably grow without adequate energy supply.

ESG 2.0

(7) What do you worry most about when it comes to the broad topic of ESG?

There may be no greater singular threat to the health of global economic growth than The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Hyperbole by me? We better hope so. This is worthy of a stand-alone post, which I am working on...i.e., the role of capital markets and insurance companies as it relates to energy transition. But when I have been asked in recent meetings and webinars whether I was worried about the impact of ESG on traditional energy, GFANZ is what I am worried about.

ESG pressure on investors will recede, or perhaps more accurately morph to be inclusive of traditional energy, as or if traditional energy continues to generate superior profitability and rises as a percentage of major market indices like the S&P 500. The far bigger threat to healthy economic growth would be if major capital markets providers or insurance companies exited the traditional energy sector, something we are seeing via recent announcements by Munich Re, HSBC, and a few others. Unlike the investor base, there are only a handful of major capital markets firms and insurance companies, the loss of which could be meaningful to financing traditional energy.

The idea that financial institutions should set “emissions-financed” goals I find to be mis-guided and absurd.

How could it possibly make sense for financial institutions to set objectives based on “emissions financed” with so much uncertainty on technology pathways, feasibility, policy, and economics for just about all future energy technologies?

How does anyone associated with GFANZ or any financial institution have in-depth knowledge about risks around execution, human capital, raw materials, and supply chain needs for future energy supply as well as demand substitutions for products that use fossil fuels in order to set targets based on “emissions financed”?

Policy pathways are highly uncertain, not only in the United States and Europe, but more importantly in China, India, and the developing world?

What is the relevance of de facto pressuring primarily US and European (and some Asian) financial institutions for non-sensical targets when those institutions generally are not dominant players in countries like China, India, the Middle East or Russia?

What is the experience level and in depth energy knowledge base of so-called “Sustainability” groups within major banks and insurance companies that are advising their C-suite and board of directors?

Why have leaders of major financial institutions signed on to targets that I strongly suspect they don’t really understand?

There is nothing “just” about what GFANZ is trying to force on major financial institutions or by extension humanity more broadly. It deserves far more scrutiny than the use of ESG among portfolio managers.

(8) Which end of the ESG spectrum do you prefer, "anti-woke-ESG" Strive or "climate activist" EngineNo1?

A bit of a trick question in that I have great appreciation and respect for how both firms are approaching what would make for a "good" energy sector investment. I don't personally believe the simplistic labels apply to either firm. While each likely has a different view on long-term oil and natural gas macro conditions and what policy and investment prescriptions are most interesting or relevant, there is a common focus on investing in profitable businesses that can thrive over the long run.

Most importantly, I do not believe either firm relies on external ESG score providers. They do their own work and have smart, passionate founders and professionals with a clear vision of what would constitute a favorable energy sector investment in their view. We need more of this kind of ESG from more traditional fund managers. Please do your own work and come to what you believe are the correct ESG considerations for companies. This is the last area that should be outsourced.

(9) But isn't ESG a scam that tries to force progressive policies that lose at the ballot box down the throats of corporate America?

The quick answer is “no”, I don’t view it as a scam or failed politics in hiding. Like anything, there is a spectrum of good and bad ESG uses. The individual metrics of Environment, Social, and Governance I believe most investors implicitly or explicitly have always considered when making an investment. I don't think there is any disputing that point. I know I used to think about these things when my career began in the early 1990s. We didn’t use these explicit words, but the basic concepts have always been part of an investment decision.

Does corporate governance line-up with my interests as an investor?

Does the executive team represent a range of experiences and view points?

Do I have to worry one of their plants will blow-up (literally) or cause environmental problems?

Examples from early in my career include the following:

Governance: The European majors’ host governments used to have what was called a golden share, which basically meant that they could take actions that the government deemed to be in the interests of its citizens but may not be in the interests of shareholders. This contributed to investors like me applying a higher cost of capital to the shares of European integrated oils, a theme that has continued to this day even with golden shares no longer existing.

Social: When US-based E&Ps I covered were expanding into certain international locations, it wasn’t always clear to me they understood how to work with the local leaders and populations, leading to project execution risk.

Environmental: One of my most successful early career calls was being a shareholder of Tosco. Tom O’Malley remains an all-time favorite CEO of mine. Tosco’s strategy was to buy refineries for “pennies on the dollar” from major oils, cut costs, improve utilization, and generate a super return on capital via higher cash flow and lower capital invested versus what the Major had experienced with the asset. It was a home run strategy. But a nagging concern of mine was whether maintenance costs had been cut too much, something difficult to gauge from the outside. I ultimately gained sufficient confidence that Tosco was unlikely to experience more problems with their refineries than any other company.

What is new and I think is the point where problems start to arise is when ESG becomes a substitute for government policy or code words for a narrowed focus on only dealing with “the urgent climate crisis.” I support the strong pushback on this part of the ESG movement. But no, I do not consider ESG to be a scam in and of itself. It’s always been part of the investment process.

🎤 Streams of the Week

Smarter Markets: A Smarter Way Episode 4 - Rob Dannenberg, Former Chief of Central Eurasia Division, CIA: link

A discussion on geopolitics, Russia, China

COBT: “It Matters Where The Barrel Comes From” Featuring Kendall Dilling, Pathways Alliance: link

A discussion on plans by Canada’s major oil sands producers to fully eliminate Scope 1 emissions by 2050

⚡️On a Personal Note

I joined JP Morgan Investment Management as it was then called in April 1995 to cover SMID-cap energy. Shortly thereafter, one of the small-cap PMs came me to and asked me to look at this company she had never heard of but was now a shareholder following its purchase of Circle K. The company was Tosco.

Tosco was led by Tom O’Malley, a veteran crude oil trader from the legendary commodities trading firm Phibro (Exhibit 5). The biggest lesson I learned from Mr. O’Malley was that making big bets that go against conventional wisdom can be a massively successful strategy.

Everyone hated refining in the 1990s. Conventional wisdom declared it a permanently low return business that at best would have very short profitability bursts. The idea of acquiring and then exploiting upstream assets discarded by the majors was something Ray Plank’s Apache succeeded with in the 1980s and 1990s. Tom O’Malley brought this mindset to US refining. It was pioneering at the time and has now been emulated many times over.

There were hiccups along the way for sure, but overall Tosco was a home-run stock to the benefit of my career. Tom O’Malley is an easy first ballot inductee into my energy company CEO Hall of Fame.

Exhibit 5: First ballot Hall of Fame CEO Tom O’Malley

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Enjoyed your post as always and agreed with much of it. Thought I’d share this very worthwhile printed debate on the subject at hand…

https://www.wsj.com/articles/coal-developing-economies-growth-11675694625

Great article as usual. One issue: I just can’t get around the energy density issue with EVs. Hybrids sure...