This week's post is aimed at everyone that shares concern about (1) Russia's role in the next world order, (2) the need for available, affordable, reliable, and secure energy, and (3) working toward a net zero ambition and addressing other environmental and biodiversity challenges. For the first time in 30 years of covering the oil & gas sector, I am officially in support of a "keep it in the ground" policy: let's further ramp-up efforts to keep Russian oil in the ground. In my view, we can best address our energy and climate challenges by pursuing policies that ensure crude oil from the United States and Canada are the "last barrels produced" in the energy transition era, no matter how long that may be.

I believe it is increasingly broadly recognized that the Permian Basin and US shale more broadly will remain a critical energy resource for decades to come. There has been less attention placed on the friendliest country on Earth: Canada. This needs to change. Canada's oil sands region is the only crude oil or natural gas basin anywhere in the world that I am aware of where the key players representing about 95% of production have formed an alliance to decarbonize (Scopes 1 and 2) production by 2050. Canadian oil is also highly competitive on profitability metrics. Good job by Canadian oil sands producers.

As an American who loves the great state of Texas, I will say shame on the Permian Basin for being beaten to the punch. But it is not at all too late for the Permian, or any other oil or natural gas basin for that matter that wants to retain a societal right to operate, to put in place basin-wide and industry-wide plans to reach net zero Scopes 1 and 2 by 2050. Greenhouse gas emissions at every level are a collective problem; while individual company promises are an important start, they alone are not enough to get the job done.

“Keep it in the ground” has been focused on the wrong regions…start with Russia, not Canada

Over the past month I have produced a series of posts, videopods, and participated in various podcasts emphasizing the need for more “good barrels” from the United States and Canada with the aim of displacing "bad barrels" from Russia and Iran. The risk/reward and pros/cons of the US shale piece I think is broadly understood in terms of the need for E&P profitability improvement (on-track) and methane emissions elimination (industry-wide progress is not where it needs to get to).

While much is made of the rhetorical hostility from the Biden-Harris Administration toward companies in its OWN country, the reality, in my view, is that it is mostly just that—rhetoric. The pace and magnitude of shale growth in coming years is overwhelmingly in the hands of E&P companies (and upstream divisions of major oils). I believe US shale can sustain world-leading growth of around 0.5-0.7 mn b/d on average per annum through the rest of this decade, while generating double-digit ROCE and moving toward a “zero” methane emissions aspiration.

The situation in Canada is more complicated and I think less well understood. US and Canadian federal government hostility toward Canadian oil has negatively impacted pipeline export capacity, relegating a portion of exported oil volumes to find alternative, higher cost and less environmentally friendly solutions like rail and truck. The idea that you can keep Canada oil in the ground by obstructing new pipeline construction runs deep among the die-hard climate crowd. It is a mis-guided ideology that deserves much more pushback and scrutiny from regular Americans and Canadians than it currently receives.

As the tragic invasion of Ukraine ordered by Russian president Putin clearly shows, when you take steps to limit oil supply from friendly countries, you simply increase reliance on bad actors. “Keep it in the ground” and its primary tool of pipeline/infrastructure obstructionism is negatively impacting energy availability, affordability, reliability, and security. And I would also argue it has come at the cost of worse climate and environmental outcomes to the extent that oil supply from countries like Russia do not employ the same degree of environmental and climate protections found in Canada (or the United States). How can any climate-oriented activist support domestic pipeline/infrastructure obstructionism without seeking to stop Russia first?

We see calls for oil company executives to be held to task for supporting 1980s-era climate mis-information campaigns and slow-footing contemporary progress toward various climate and environmental initiatives. I suspect Russia-Ukraine will be the catalyst for non-energy specialists to wake up to corresponding mis-information campaigns from various politicians, policy makers, and the die-hard climate crowd about the damage domestic (US and Canada) “keep it in the ground” initiatives does to all aspects of energy and climate policy. A healthy energy transition era solves for all aspects of energy and climate policy—availability, affordability, reliability, and security, along with improving climate and broader environmental goals. “Keep it in the ground” via US/Canada pipeline/infrastructure obstructionism solves exactly zero of these objectives.

Instead, I would propose both the die-hard climate crowd along with the rest of humanity that already recognizes we will be using meaningful quantities of crude oil for many more decades to band together and focus on a common enemy: Russian oil. In order to ensure we have available, affordable, reliable, and secure energy as we are displacing Russia, in addition to US shale the world would absolutely benefit from more Canadian energy.

Canadian Big-4 Oils profitability has been better than US shale E&Ps

One of the common arguments against Canadian oil from an investor perspective is that it is supposedly a “high cost” barrel. The argument is usually based on a future project cost of supply analysis. Having contributed to such analyses over the course of my career, I have a uniquely deep understanding of the perspective. However, as has been demonstrated unfavorably with US shale, there can be divergences between the project-cost analysis and corporate level returns. In the case of the Big 4 Canadian oils, the variance is favorable, with US shale it was unfavorable (i.e., corporate returns were much lower than implied project level profitability for US shale).

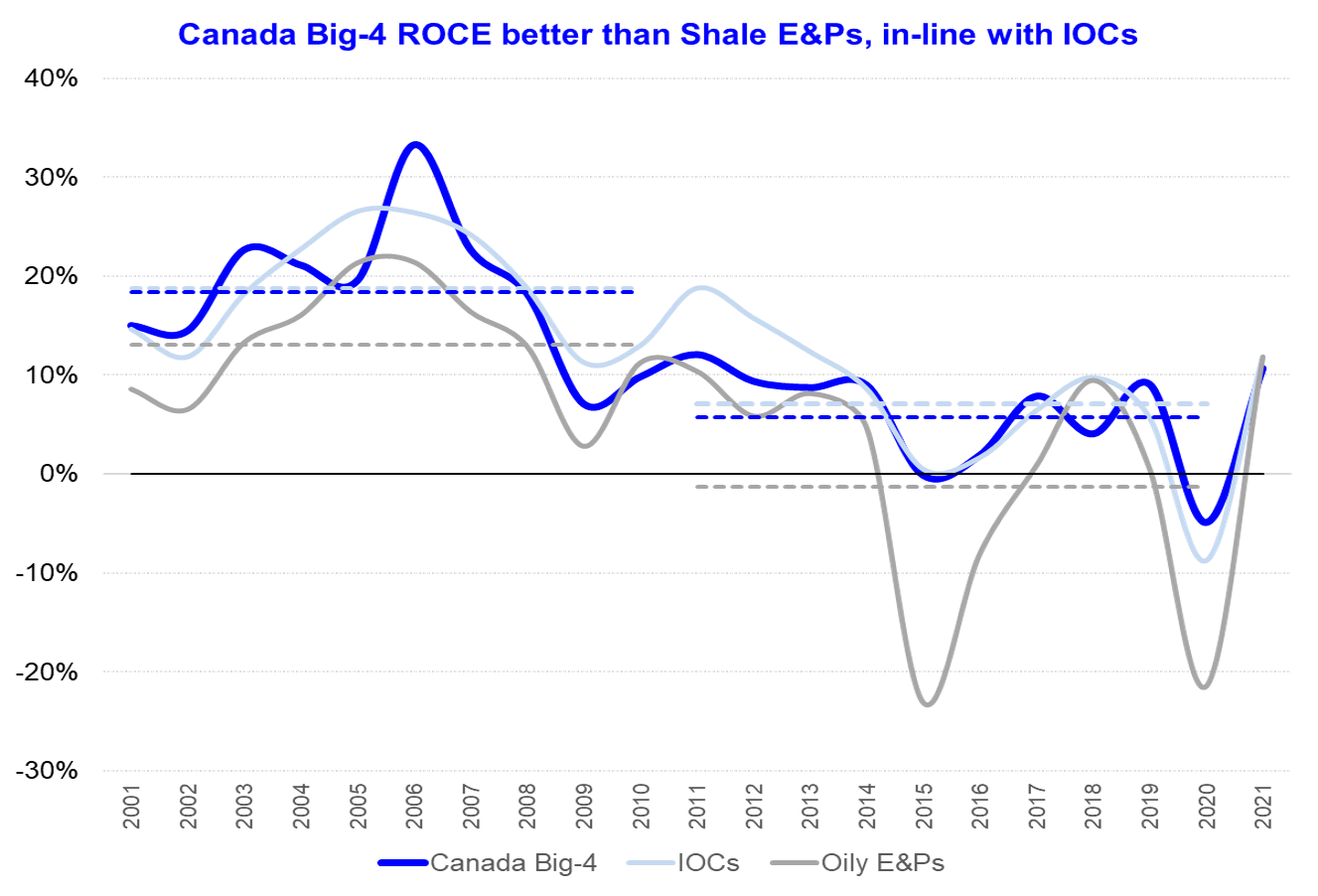

As shown in Exhibit 1, the Big-4 Canadian oils have consistently outperformed US shale oil E&Ps on return on capital employed (ROCE) and have actually performed broadly in-line with the international oil majors. Over 2001-2010, Canada’s Big-4 generated an 18.4% average ROCE versus 18.7% for the international oil majors and 13.0% for the US shale oil E&Ps. Over 2011-2020, Canada’s Big-4 average ROCE was 5.7%, just below the 7.0% from the international oil majors and well ahead of the -1.3% for US shale oil E&Ps (yes, ROCE last decade was poor for all of traditional energy). The Big-4 Canadian oils include Canadian Natural Resources, Cenovus Energy, Imperial Oil, and Suncor Energy.

Exhibit 2 highlights the superior free cash generation of Canada's Big 4 versus US shale oil E&Ps by looking at a reinvestment rate analysis. Reinvestment rate is defined as CAPEX divided by cash flow from operations—a number over 100% implies negative free cash flow and below 100% positive free cash flow.

Long-lived oil sands production a good balance with shorter-lived shale oil

A major positive of Canada’s oil sands region is that production is long-lived, with individual projects generally targeting around 25 years of constant production with minimal maintenance CAPEX after significant upfront capital spending. In contrast, US shale oil supply requires less upfront spending before first production but exhibits much faster initial decline rates (years 1-3), though tail production can last for 25+ years as well.

Current US + Canada oil (i.e., liquids) supply and demand are around 23 mn b/d out of a global market of around 100 mn b/d. I am unaware of any reasonable pathway to global oil demand being below 30 mn b/d in 2050. My order-of-magnitude expectation for 2050 is 75-120 mn b/d of oil demand.

It is time to push back on the mis-information campaign that points to the long-lived nature of Canadian oil as a reason to NOT invest in it and that cedes “last barrel” status to Middle East producers. We hear this not only from climate activists, but, more concerningly, from policy makers and politicians as well. It is in the interests of the United States, Canada, and their allies to benefit from more Canadian energy.

Oil Sands Pathway To Net Zero

Unlike every other oil and natural gas basin in the world (from what I can see), the six leading Canadian oil sands producers that account for 95% of oil sands production have joined forces to achieve a net zero ambition by 2050. According to their information document (here), the Pathways goals are:

Working collectively with the Federal and Alberta governments to achieve net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from oil sands operations by 2050 and help Canada meet its climate goals, including its Paris Agreement commitments and 2050 net zero ambitions.

To reduce current total oil sands GHG emissions of 68 Mt of CO2e/yr in three phases by 2050.

The pathways foundation project is a major carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) system and transportation line connecting oil sands facilities in the Fort McMurray, Christina Lake, and Cold Lake regions of Alberta to a carbon storage hub near Cold Lake. To be sure, there are many uncertainties on the cost and feasibility of the magnitude of CCUS contemplated here.

In my view, it is in industry’s interest to hold itself accountable to demonstrating progress and being transparent on how the CCUS Hub is progressing. But it is also in the interests of politicians, policy makers, and climate/environmental groups to acknowledge that if net zero is the goal, Canadian oil sands producers have perhaps the strongest and most credible plan in the world (relatively speaking).

What are other oil and gas basins doing to achieve net zero Scopes 1 and 2?

Kudos to Canada's oil sands producers for being first to formulate a basin-wide net zero by 2050 plan. The question for other major oil and gas basins is: What are you waiting for? We are at the start of a major new upcycle. Returns on capital, free cash flow, and cash returned to shareholders are all improving. Most of you as individual companies have stated net zero by 2050 ambitions. Why is it taking so long to come together to solve an increasingly solvable methane issue? How about implementing an industry-wide, basin-by-basin phased approach to eliminating Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2050 (or some year)?

Investors are ready to embrace the oil and gas sector again. Waiting out the remaining term of the Biden-Harris Administration is not going to win over generalist investors, even if it feels like the safe and easy approach to some of you. There is significant multiple expansion potential that could be attached to the improved profitability with a credible decarbonization effort (Scopes 1 and 2) that gives generalist investors confidence that American (along with Canadian) crude oil will be the last barrels produced in the energy transition era, which, I agree, is still many, many, many decades away.

The goal: +10 mn b/d of net exports from USA+Canada by 2030

I have outlined the key goal in recent posts (here) and (here). I see a pathway for US + Canada liquids supply/demand to move from its broadly balanced state in 2022 to 10 mn b/d of net exports by 2030. My base-case pathway reflects +5 mn b/d from US shale, +3 mn b/d from Canada, and +2 mn b/d from lower US oil demand (versus baseline demand); risk to the mix is skewed to higher US oil supply offsetting a non-decline in US oil demand. The Canada piece is the most uncertain as it reflects a meaningful reduction in the hostility shown by the current US and Canadian federal governments toward new pipeline/export infrastructure. There is no guarantee common sense and pragmatism will ever prevail.

⚡️On a personal note… CORRECTION

I am in need of my first Super-Spiked CORRECTION. Somewhat crazily, it actually comes from the “On a personal note…” section. I made a very basic analytical error in calculating my family’s battery electric vehicle (BEV) car park share that I regularly castigate many “peak oil demand” forecasters for making. No one alerted me to the error; rather, I recognized I had made it when discussing EV sales projections in an unrelated meeting. Ugh.

As a recap, I noted that in 2020 my family purchased a Model 3, a BMW X5, and a Subaru Forrester, resulting in a 33% BEV share of our new sales (67% share for internal combustion engine, or ICE, vehicles). I also stated that our car park was 33% BEV. The latter was wrong based on lazy analysis. Since we did not junk our previous vehicles and instead traded them in to the respective dealer, they should still be counted in the family car park calculation.

For those not familiar with the need to differentiate between annual sales and the total vehicle stock, car park is the measure of the total fleet of vehicles in existence and not simply how many were sold in a given year. For example if you simplistically assume (1) the total fleet of vehicles on the road in year 0 is 1 billion vehicles; (2) vehicles have a 10 year life and are then junked; (3) annual sales are 100 million vehicles per year; and (4) sales move from 0% BEV and 100% ICE in year 0 to 100% BEV and 0% ICE in year 1, the car park at the end of year 1 would be 10% BEV and 90% ICE.

Below is my recollection of the vehicles we have purchased since family formation. I would note that we were a one vehicle family in 2001-2002, a two vehicle family from 2003-2019, with a 3rd vehicle added in 2020.

Toyota Camry (2001) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Audi mid-sized SUV (2003-ish) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Toyota Hybrid (non-plug-in) Highlander (2006) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Toyota Camry (2008) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Infiniti M37X (2013) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Infiniti QX80 (2014) ⛽️ (Traded in)

Tesla Model S (2015) 🔋 (Traded in) (⭐️ - favorite car owned)

Tesla Model 3 (2020) 🔋

BMW X5 (2020) ⛽️

Subaru Forrester (2020) ⛽️

That is a total of 10 vehicles purchased for two primary drivers over 20 years of which 20% (2 out of 10) were BEVs. If I limit cars to a 20 year life, our existing car park BEV share rises to 22% (2 out of 9). If I shorten that again to 15 years, we would be at the 29% BEV car park share (2 out of 7). I obviously do not know how many of the cars we traded in are still on the road today. Shame on me for this basic error that I routinely highlight in analyses made by others.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. A subsidiary of a company I am affiliated with is a founding partner in the Oil Sands Pathway to Net Zero. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Terrific…I own almost exclusively Canadian small/mid like MEG BTE whose torque and free cash flow yields are ludicrous

You make too much sense!