From Not-For-Profit to a New ROCE Super-Cycle

ROCE Deep Dive Post #1: Capital allocation more important than oil price over long run

I believe 2021 will mark the start of a new ROCE super-cycle era for traditional energy, reversing a 15-year downturn.

Traditional energy was a not-for-profit sector generating a 0%—zero!—ROCE over 2016-2020; extending to 2011-2020 was not much better at a paltry 4%, not dissimilar from a muni bond portfolio. The end of the Super-Spike era and onset of the shale oil revolution has been a disaster for traditional energy.

In contrast, ROCE was a healthier 11% during the pre-Super-Spike era of 1991-1999 and averaged 14% if you extend to 2010 and include the boom period. The 1990s prove that acceptable profitability levels are not dependent on booming oil prices.

Energy’s weighting in the S&P 500 was 12% in 1991, 12% at the end of 2010, but crashed to a low of 2% in October 2020 and is now just slightly higher at 2.8%. While oil prices and energy transition concerns get disproportionate attention from all types of energy observers, in my view, the sharp deterioration in sector ROCE explains a large portion of the diminished relevance.

I believe that capital allocation is the most important determinant of sector profitability. If a sector (or company) doesn’t ultimately earn a competitive return on capital, it does not deserve to perpetuate.

Though often an important variable over shorter time horizons, long-term energy ROCE cycles are ultimately not driven solely by commodity prices as is often perceived. While I believe oil prices are likely to be in a “high and volatile” band in coming years, I do not personally use the “super cycle” moniker to describe my 2020s oil price outlook. This is not a post about oil prices; it is about the far more important topic of ROCE—oil prices are just one, albeit high profile, variable in evaluating energy sector profitability.

Structural energy ROCE cycles are measured in 10-15 year increments and should be differentiated from shorter-term trading noise driven by ongoing oil & gas price volatility or company-specific considerations. In my view, 2020 marked the end of a 15 year ROCE downturn (2006-2020), with 2021 the bullish inflection.

Capital allocation within the sector appears to be improving. Most notably, reinvestment rates are on-track to be meaningfully lower in coming years, a key driver of higher ROCE. It is logical—if you wasted investor capital for the last decade, spending less capital is Bad Capital Allocators Anonymous Step #2 (Step #1 is always admitting you have a problem; that occurred in 2020). I am encouraged by what I have seen in the first three quarters of 2021; 17 more like these would yield an excellent five-year track record.

This is post #1 in what will be a multi-part, deep-dive look at sector and company-specific profitability drivers. I am not looking to write a book in one go here and this introductory post is already too long; hence, the decision to split it up into a multi-part series that will serve as an enduring theme of Super-Spiked. My goal is to educate, dispel common myths about the sector—some of which hold true over shorter-term periods (<3 years)—and to differentiate what drives long-term sector leaders from laggards.

Moreover, I am not trying to come across as lecturing oil & gas management teams; I am merely trying to highlight what I think will be the key to re-gaining investor interest. If there is a goal to ultimately having a non-messy energy transition, a profitable and healthy oil & gas sector is critically important, in my view. As a reminder, this is not an investment newsletter and no financial advice is being provided, implicitly or explicitly.

Two major ROCE cycles over the last 30 years: 1991-2006 UP, 2006-2020 DOWN

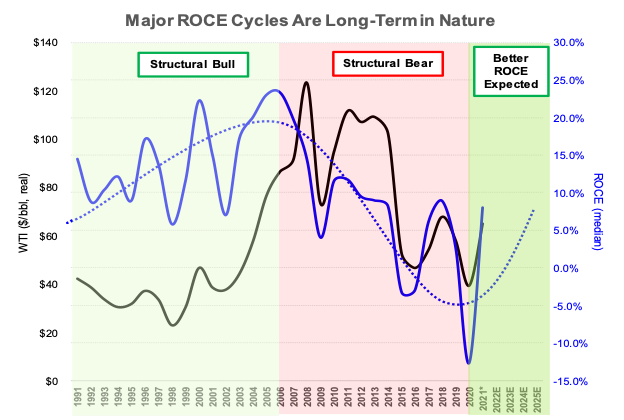

The past 30 years have witnessed two structural ROCE cycles: the up years of 1991-2006 followed by the down years of 2006-2020 (see Exhibit 1). Perhaps the most important takeaway is that the oil price cycle does not fully align with the UP and DOWN ROCE eras. In fact, long-term ROCE trends appear to have a better relationship over time with energy’s weighting in the S&P 500 (see Exhibit 2).

The 1990s were a generally favorable period for ROCE generation for the top two quartiles of energy companies, a period when WTI was uninspiring and trading between $14-$22/bbl (nominal).

ROCE actually peaked in 2006 at around $70/bbl WTI, two years prior to the 2008 nominal peak of $147/bbl.

The post Great Financial Crisis (GFC) period from 2009-2014 was generally a “$100/bbl” oil price era. Notably, trend sector ROCE only went in one direction—down— as capital intensity rose sharply and managements/boards/analysts assumed a high oil price regime was “permanent”. Mistakes were made.

It bears repeating as its own bullet: ROCE peaked in 2006 at $70/bbl and never came close to those levels despite a $30/bbl higher oil price in 2009-2014. How did that happen? In a nutshell, poor capital allocation was the culprit.

I believe 2020 marked the end of a 15 year structural downturn in ROCE that took the Energy sector from a peak of around 15% of the S&P 500 to a low of 2%. As we see in Exhibit 2, sector ROCE broadly correlates with its S&P 500 weighting.

Most importantly, my more favorable outlook for 2020s ROCE is not predicated on a new oil price “super-cycle”, though I do expect a high and volatile trading range to be the reality as we enter what looks like a very messy energy transition era. While shorter-term ROCE movements do indeed wiggle with the oil price, the long-term trends do not.

Exhibit 1 shows median energy sector ROCE from 1991-2021 versus real ($2020) WTI oil prices. The asterisk for 2021 denotes it is for the first three reported quarters of the year.

Exhibit 2 shows the relationship between median sector ROCE and the sector’s S&P 500 weighting over time. As with Exhibit 1, the 2021 ROCE data point is for the first three quarters of the year.

Back to the Future: 1990s were a workman-like era where top quartile companies generated competitive ROCE

For the introductory post to the Super-Spiked ROCE deep dive series, I thought it made sense to start with the workman-like, pre-Super Spike 1990s era. In this period, the commodity price environment was lackluster, and only companies that embraced a grind-it-out, focus-on-returns mindset thrived. It is the best example of how good management teams can really make a difference and where the differentiation between good and evil are most visible. No tailwind (i.e., rising oil prices) to falsely take credit for, but also no headwind (i.e., falling oil price) to mask otherwise good decisions.

Several things stand out. First and foremost, the 1990s did not feel like an especially good period for Energy and I suppose it wasn’t. During the 1990s, WTI crude oil traded in a modest $14-$22/bbl (nominal) range (full-year basis) that everyone absolutely knew, without a shadow of doubt, would be the permanent and forever oil price range. We wound never, ever have an “artificially” high oil price era again. The 1970s were an Arab Oil Embargo-driven aberration per the prevailing views. Only the dinosaur analysts that were clinging on to life (I assure you they bear no relationship to any former Goldman analyst that recently started a Substack) thought there might some day be a return to a sustainably stronger oil market. I remember it like it was yesterday having intense debates with global oil team colleagues as to whether the long-term WTI oil price would be $18/bbl, $17/bbl, or $16.50/bbl. Yes, we argued over $0.50-$1.00/bbl increments in those days!

Perhaps most remarkably, during the 1990s the median ROCE for the sector averaged a solid 11%. In the battle between good and evil, the median top half (i.e., 1st and 2nd quartiles) ROCE averaged 17% ROCE versus a 5% average for the bottom half of the sector (3rd and 4th quartiles). Most impressively, the median ROCE for the good guys (i.e., the top two ROCE quartiles) was 10% in 1998, a trough-of-cycle year when WTI averaged $14/bbl during the Asian Financial Crisis. I would surmise that just about any cyclical company would be thrilled to earn a 10% “cost-of-capital”-like ROCE at the trough of their respective cycle. That is the gold standard.

Exhibit 3 shows median energy sector ROCE from 1991-1999 as well as median top half (1st and 2nd ROCE quartiles) and bottom half (3rd and 4th quartiles) ROCE versus nominal WTI oil prices.

Lesson #1: High and rising commodity prices are not a prerequisite to generating competitive ROCE in the oil & gas business.Lesson #2: Nothing is forever or pre-ordained, least of all commodity-sector ROCE cycles.Reinvestment rates a key driver of good versus evil

The question for investors and managements alike is for a given oil price backdrop, how do you explain such stark differences in performance? By using top half versus bottom half median ROCE, the sample size is sufficiently large so as to not have the outlier excuse.

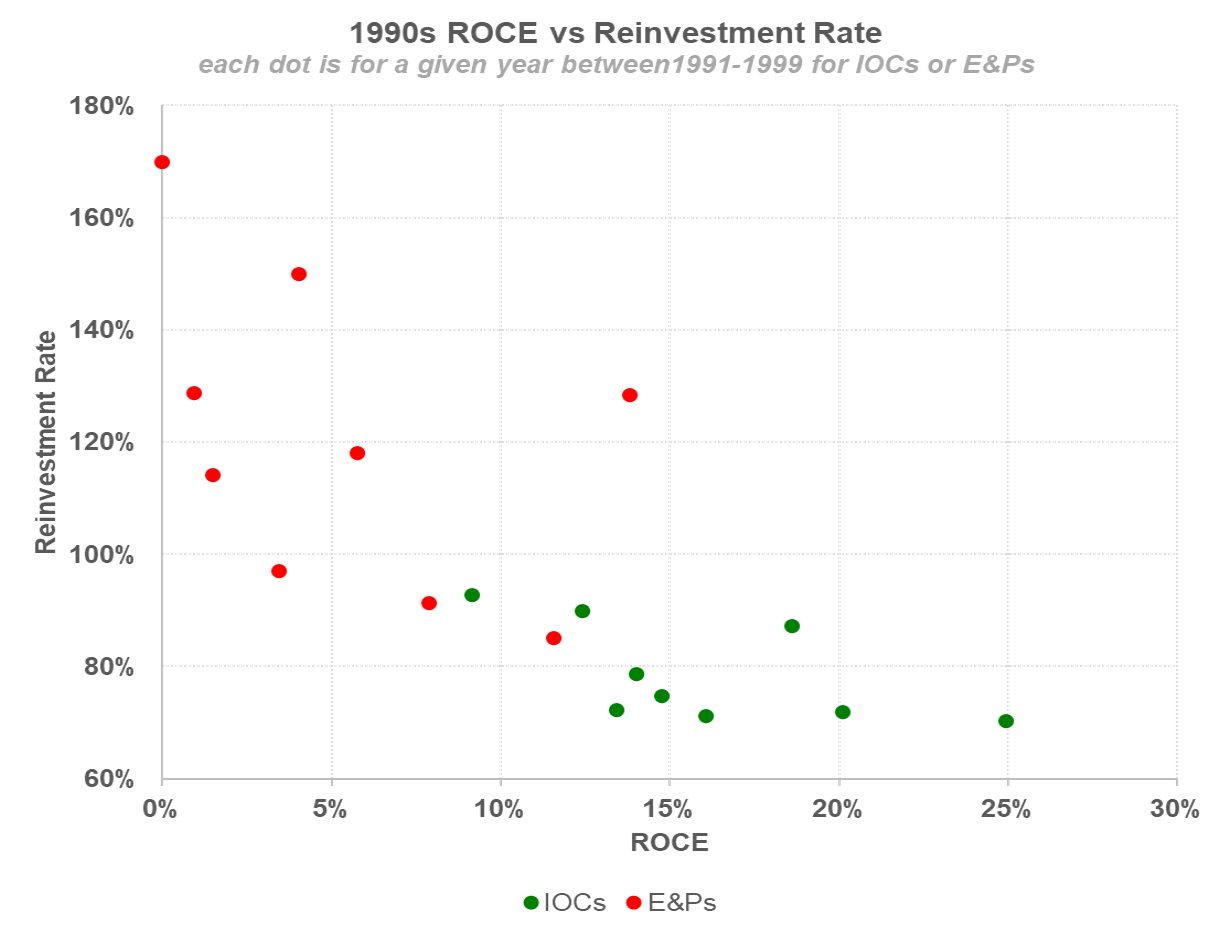

Exhibit 4 provides one potential explanation: reinvestment rates. For this analysis, I am switching to comparing IOCs versus E&Ps rather than the top half vs bottom half ROCE division used thus far. Three reasons for the switch: (1) this is a long-accepted sub-sector split and yields results that long-time energy observers will find intuitive; (2) in those days, IOCs in generally earned higher ROCE than E&Ps, consistent with the point I am trying to make; and (3) I don’t trust myself with Microsoft Excel’s INDEX/MATCH function to easily sort ranked ROCE with the corresponding company reinvestment rate. (Disclosure: I am very much missing the outstanding junior analysts I had at Goldman who could confidently and quickly create the appropriate INDEX/MATCH function for this kind of analysis; “JC”, “WS”, are you out there? If I hand sorted the data, this won’t get published for another week.)

As you can see in Exhibit 4, in Energy, reinvestment rates are inversely correlated with ROCE. Said another way, the more you spend, in general, the worse the profitability. This is the reason energy investors are instinctively skeptical when managements talk up the virtues of growth via higher capital spending budgets. I will expand on the growth versus returns trade off in a future note; it is usually the biggest mistake made by most E&P management teams.

Generating higher ROCE is not necessarily as simple as reinvesting less, but it usually is the place to start. Where this goes wrong is in the trade-off with volume growth as a field/asset matures. Unlike other businesses, oilfields are not forever. Once an oilfield enters long-term decline, managements will typically need to spend in new areas in order to at least sustain production volumes. Whether this is positive, negative, or neutral for ROCE will be driven by how well they execute on finding and developing new fields. That discussion is for another day. The simple point of this note is to highlight that reinvestment rates plays a big role in determining “good” versus “evil” ROCE generation.

Current reinvestment rates have dropped sharply

My favorable ROCE outlook for the coming era is sparked by the sharp drop in reinvestment rates seen by industry broadly and the E&P sector (see Exhibits 5 and 6, respectively). To be sure, CAPEX is likely to increase in coming years—it is critical that it does or we will in fact have an oil price super cycle due to insufficient non-OPEC supply growth. But the commitment to sustained lower reinvestment rates and higher cash returned to shareholders I believe is here to stay, at least for the foreseeable future.

ExxonMobil: Greatest Company in the History of the World (1885-2008)

No company better exemplified the idea that you could consistently generate strong ROCE irrespective of commodity prices than ExxonMobil (and legacy Exxon). My standard Exxon tag line going back to my Goldman coverage was: “Greatest Company in the History of the World.” What other company dominated its industry at its founding in the late 1800s, at the turn of two centuries (1900 and 2000), through World War I, World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam War, for the full duration of the Cold War, 9/11, and at the start of the Great Financial Crisis.

I can still hear Lee Raymond’s sage words (paraphrasing): “We are not trying to guess where oil prices will go. Instead, we are only going to invest in projects that will be at the low end of the future cost curve. Over time, we believe only those projects will deliver acceptable returns on capital. Production is an outcome of our investment process. The only goal is for CAPEX to be redeployed at the lower end of the future cost curve. Any project that doesn’t meet that criteria will not be funded. If we generate excess cash flow in a given period, it will be returned to shareholders or used to strengthen our balance sheet. Over long periods of time, we have demonstrated we can deliver higher total shareholder returns than the S&P 500 with lower levels of share price volatility.”

Despite whatever crosses Mr. Raymond may bear for ExxonMobil’s long-standing and unfortunate “delay and deny” stance toward climate change (they began to change their tune under Mr. Raymond’s successor, Rex Tillerson; this is not a note about Exxon’s stance toward climate change), there is little doubt in my mind that Lee Raymond will be remembered as one of the all-time greatest allocators of capital in the history of business. As a capital allocator, Lee Raymond should be revered.

Those of you with only a more recent history with ExxonMobil can’t imagine what I am talking about as the company veered off course post Mr. Raymond’s retirement. As you can see in Exhibit 7, Exxon’s ROCE peaked in 2008 and has since disappointingly declined to sector averages by 2020. Within this 30 year history, not only had Exxon never lost money on a full year basis prior to 2020, but had generally earned “cost of capital” like ROCE or better at industry troughs. A deep dive analysis of what knocked ExxonMobil off course is for another day. I did discuss ExxonMobil on a Business Breakdowns podcast earlier this year, which you can find here or on your favorite podcast player.

Exhibit 7 shows ExxonMobi’s ROCE versus the energy sector median and the bottom half of the sector. In this exhibit, real WTI oil prices ($2020) are used.

On a personal note…

This ROCE Deep Dive series is dedicated to my former colleagues at J.P. Morgan Investment Management circa 1995-1999 who started me on the path to embracing long-term, normalized ROCE. I have been fortunate throughout my career to have had great mentors: Dr. Ron Rizzuto at the University of Denver, Paul Leibman at Petrie Parkman & Co., “Chris X” at JPMIM, and a number of partners/colleagues at Goldman and elsewhere on the Street.

Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Appendix: Definitions and Clarifications

ROCE - Return on capital employed = (Reported net income + after-tax interest expense) divided by average capital employed (Total debt + shareholder’s equity - cash). By using reported net income, write-offs are not “forgiven” in this long-run analysis as might make sense to do for a particular quarter or individual year.

Other return metrics. There are many ways to evaluate profitability. An alternative metric is cash return on gross cash invested (CROCI), which uses debt-adjusted cash flow from operations (excluding working capital changes) divided by gross cash invested (capital employed grossed up for accumulated DD&A primarily). What I don’t like about CROCI is it doesn’t notionally adjust for maintenance CAPEX. While DD&A has its own imperfections, ROCE at least attempts to incorporate a notion of maintenance CAPEX (i.e., spending to hold production volumes flat). “Free CROCI” is an alternative, but estimating maintenance CAPEX on a year-to-year basis leaves too much wiggle room. DD&A over time should correspond to a company’s capital intensity to maintain (or grow/shrink) the business.

All data used in this post is sourced from S&P Capital IQ and Bloomberg. When discussing the broad traditional energy sector, I am including US and European integrated oils, US and Canadian E&Ps, US refiners, and US oil services. An effort has been made to include historical data from companies that have since merged.

Great article - really educational. Learning a lot from your Substack.

Thanks for this Arjun, a really insightful piece. I was delighted to see that you launched Super-Spiked a few weeks back.

Look forward to following along going forward.