Last week I discussed my view that normalized ROCE for the top two quartiles of traditional energy companies would average 20%+ during the 2020s. The recovery is here and we are in the early days of what I think will be a decade long energy bull market (with lots of ups and downs along the way, as always). This week I turn to the more complex topic of "cost of capital" and the impulse, or lack thereof, for growth CAPEX to return.

In a nutshell, I would argue that although ROCE is up sharply, the oil & gas industry's cost of capital has stayed "high", or at least higher than expected given the corresponding improvement in profitability. A simple graph illustrates the point: energy's weighting in the S&P 500 remains well below its earnings weight or what is implied by the improvement in ROCE (see Exhibit 1).

From a markets perspective, bulls would argue traditional energy equites are "cheap" (assuming it is early days of a structural bull market) and to stay overweight the sector; bears would argue oil prices (and ROCE) are unsustainably high and likely to fall and therefore energy equities should be avoided at this time. That long-standing debate is NOT the point of this note.

Rather, it is my observation that despite a marked improvement in profitability and a clear demonstration from managements/boards that greater quantities of cash flow will be returned to shareholders than seen in past cycles, there is still a deep caution to embracing the sector. Said another way, "cost of capital" remains higher than I might have expected and its contributing to a reluctance for any semblance of a new CAPEX cycle that is clearly needed.

So I ask:

Why hasn't CAPEX rebounded more meaningfully?

When will it?

Should it?

Can it?

From a markets perspective, the bearish call on energy equities is usually justified after capital intensity rises sharply; not before it has even started. So far, this cycle is not playing out like prior super-cycles.

In my view, a variety of hurdles have sprung up since the last major CAPEX cycle over 2002-2014 that is likely to keep the CAPEX response slower than it has historically been. This means a slower energy supply response and more dependence on "demand destruction" to keep supply/demand in balance. One can reasonably debate the degree to which any particular hurdle is weighing on CAPEX; in reality it is a confluence of factors, none of which are totally independent from each other. The bottom line is the industry's cost of capital, in particular its cost of equity, is staying stubbornly high as investors demand a higher hurdle to be cleared than it has historically required before (possibly) being accepting of a new CAPEX cycle.

A slow CAPEX response...commodity cycles don't end before there is a CAPEX cycle

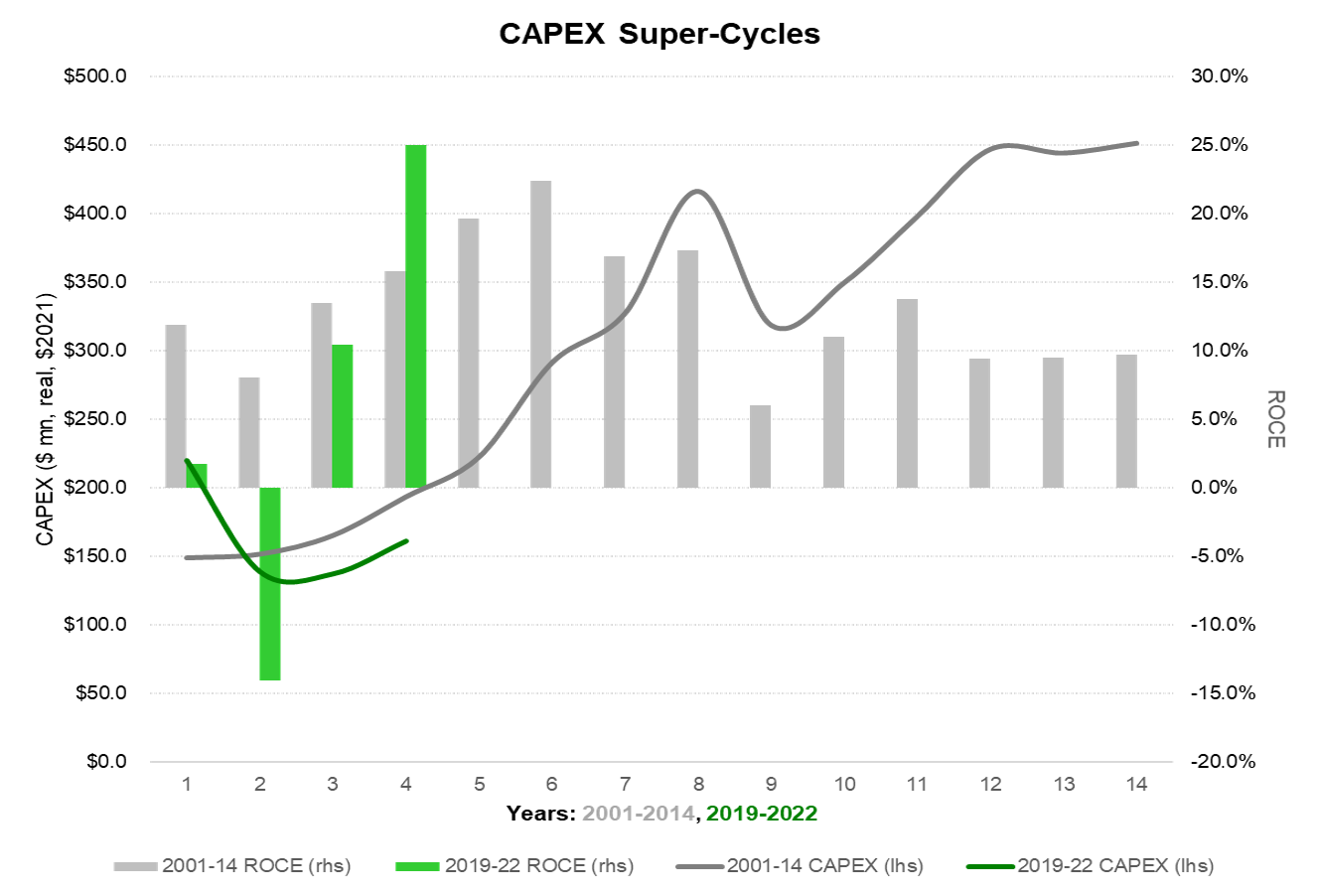

Exhibit 2 shows real CAPEX ($2021) for publicly-traded traditional energy comparing the 2001-2014 Super-Spike era to the New Energy Crisis Era. For the latter I am using 2019 as the base-line, which I think is consistent with starting the prior era in 2001 (feel free to pick your own start/stop dates). Notably, ROCE has accelerated much more quickly than last time; yet there are few signs that we are on the verge of a major CAPEX pick-up. In fact, for the first time in my 30 year career, returning cash to shareholders has displaced production growth as the key metric.

Possible reasons the CAPEX response has been muted thus far (ranked in my estimation of order of importance):

Memories of strong promised returns (i.e., well IRRs) resulting in essentially 0% corporate level ROCE last decade remains fresh in the minds of investors and oil company managements/boards. Similarly, profitability from the mega projects pursued during the first part of the 2010s did not live up to original expectations (though that may be changing in the new $100+/bbl environment).

Concern that the current spike in oil prices over $100/bbl is mostly due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and could reverse suddenly if hostilities subsided. In other words, investors are unwilling to capitalize what they perceive to be transient cash flows; the related presumption would be that "normalized" oil prices are well below current levels and do not justify a major CAPEX cycle.

Concern that a US or global recession may be near which could weaken oil prices.

Concern that long-term (2030+) oil demand could plateau and possibly decline due to climate policy initiatives (e.g., fuel economy, electric vehicles, etc.).

Concern that needed export infrastructure will face regulatory delays and obstructionism by environmentalists (in particular applies to Canada's oil sands and Appalachia natural gas).

Concern by some investors that an investment in the oil & gas industry would violate ESG or "net zero" principles. (And by definition there is a corresponding lack of concern of the damage an energy crisis will have on just about everybody, in particular those least advantaged. It is beyond the scope of this post to analyze why do-gooder principles don't consider the least fortunate most negatively impacted by their policies.)

Overt hostility from the current US and Canadian federal administrations is completely unhelpful, but at the end of day is more noise than substance, in my view. The one exception is the unwillingness to support inter-state pipeline infrastructure is real and a big problem, and an area where a more constructive stance from the Feds is badly needed.

Cost of capital: CAPM versus market implied

It’s become a somewhat lazy saying among finance professionals to discuss the need for returns on capital to exceed cost of capital. But what is cost of capital? While there are plenty of debates about the pros and cons of various profitability metrics, such metrics are at least definitively calculable. What is less clear cut is what analysts and investor really mean by "cost of capital".

In my view, the textbook capital asset pricing model (CAPM) definition of cost of capital leaves a lot to be desired in addressing the appropriate hurdle rate companies face in the real world. The Investopedia definition (here) considers the CAPM-defined cost of capital to be the risk-free rate (traditionally long-term US Treasuries) plus the market's risk premium to the risk-free rate adjusted for a particular company's beta to the broader market. You can go to the link for a perfectly acceptable discussion and video on the pros/cons of this approach.

The textbook CAPM model does yield an "answer". I just don't think the answer is particularly useful or practical. There is no chance that a company's cost of capital when trading at a 25X P/E using peak EPS is the same as after its stock falls by 50% due to an industry or company-specific downturn. The quantity of equity that would need to be issued for a potential acquisition as an example is obviously significantly greater at the lower stock price and could well be limited in size due to a lack of sufficient investor interest after a downturn.

My preference has been to use market-based cost of capital metrics. To some degree, this is simply a fancy way of discussing valuations like price-to-earnings (P/E), enterprise value to cash flow (EV/EBITDA), or price to book value (P/B), with adjustments being made to either "normalize" commodity prices (i.e., an expected long-term average) or solve for an implied discount rate (i.e., "cost of capital") based on a set of assumptions.

I like and generally use the idea of back-solving for an implied discount rate based on future cash flows. The challenge of course is that it is subject to a host of assumptions that can dramatically change the result. In my view, this gets closest to a better understanding of a pragmatic cost of capital so long as one is clear about the future scenarios being assumed.

Cost of capital example: Exxon v. Hess - Then and Now

It might be easier to use an example to illustrate these points. I am going to use price/book value to illustrate my example, as recreating the cash flow expectations for Exxon and Hess in the 1990s would unnecessarily delay this post and doesn't change the conclusion (Exhibit 3). I would note for the purposes of this exhibit and analysis, it is really the relative direction that matters most and what it says about a company’s right to spend. You can see the outperformance of Exxon in the 1990s, especially in the “Nifty 50” peak in the late 1990s and then Exxon’s structural de-rating post 2009 when ROCE fell. In the case of Hess, sentiment has improved markedly since Guyana was discovered and its previous extreme cost-of-capital disadvantage to Exxon has gone away.

In the 1990s, under CEO Lee Raymond, Exxon had cracked the code on securing investor interest: best ROCE in industry, fortress balance sheet, profitable at the industry trough (1998), consistent capital returns to investors, absolute growth was an after thought. Sound familiar? Mr. Raymond used to show one of my favorite all-time graphs that on a rolling 10-year (or 20-year) basis, Exxon had a higher total return than the S&P 500 but with lower annual share price volatility. Incredible! Exxon, one company, and an oil company at that, had a better Sharpe ratio (Investopedia definition link) than the entire S&P 500. As the reality and mystique of Exxon grew, so did its valuation. In the semantics of this note, the market continuously lowered Exxon's cost of capital. The belief was that the Exxon machine could spit out sustainably superior ROCE irrespective of the ups and downs and general carnage around it.

In contrast, Amerada Hess, as it was then known, in the 1990s was a bit of mess. It was an accumulation of assets, both upstream and downstream, that struggled to generate profitability, free cash flow, or growth. It was the quintessential deep value stock, but one that turned out to be a value trap during the 1990s. It's valuation was low; its cost of capital was high. Amerada Hess did not have a license to spend money; the Street did not trust management with capital allocation in those days.

The 2000s super cycle benefited both Hess (Amerada was excised from the name) and what turned into ExxonMobil (Exxon's final great move under Mr. Raymond). To everyone's surprise that lived through the 1990s, when the dust settled post the Super-Spike era, it has been Hess that has come out on top. A series of mistakes and an inability to appropriately evolve post Mr. Raymond undid ExxonMobil. Hess streamlined itself and participated in the discovery of Guyana (somewhat ironically operated by ExxonMobil). The cost of capital flip has been dramatic—i.e., the willingness to accept growth from Hess but mandate discipline from ExxonMobil.

In the case of Guyana, investors appreciate it is a massive, low-cost resource and are generally supportive of the decision to spend capital. Hess had earned the right to spend money via good decisions it made to streamline during and after the Super-Spike era. Guyana is a gift from heaven.

In the case of Exxon, it thought it had earned the right to spend. But the reality was that the 2009 acquisition of XTO Energy was the clearest evidence that the good ole days of the Lee Raymond-run ExxonMobil were a thing of the past. Post Mr. Raymond, Exxon thought it could pursue a high CAPEX growth model. It was mistaken. Exxon's previously untouchable ROCE advantage completely collapsed in the 15 years following Mr. Raymond's retirement; investors lost trust in management's ability to prudently allocate capital and its cost of capital increased.

Lessons from Exxon v. Hess

Being an early entrant in a massive, new, low cost oil field is always a good thing that investors like and will support.

Making a high-cost, after-the-fact acquisition of a company that itself had rolled up assets at lower price points is usually a bad move.

Confidence in future ROCE ultimately matters more than past performance (Guyana with Hess).

Strategies need to evolve for the future cycle. In the first several years post Mr. Raymond's retirement, Exxon did not pivot to what the next cycle required until it was way too late; it then proceeded to compound its mistakes with poor capital allocation decisions (not just my opinion, judging this based on its subsequent ROCE collapse).

Cost of capital is not static; it is about future expectations.

Hess lowered its cost of capital at a time traditional energy has been very out of favor and there have been concerns about what energy transition would mean for the crude oil business; yet, investors still liked its participation in a massive, low-cost crude oil reservoir.

So what will it take to restart the CAPEX engine for the New Energy Crisis Era?

Investor trust that managements will allocate capital wisely.

Confidence that low-cost resource/projects are being developed.

Recognition that crude oil and natural demand is not going away any time soon.

A regulatory and environmental policy regime that supports growth in critical infrastructure with an appropriate balance for enviornmental and climate considerations.

Point #4 likely requires elections in the western world to usher in energy-knowledgable politicians and policy makers; be wary of “climate only” ideology.

⚡️ On a personal note…

Lee Raymond was Exxon's CEO when I began covering the company in 1995 at JPMIM. He was my CEO hero at the time and the gold standard on prudent capital allocation. I usually credit my colleagues at JPMIM for my normalized ROCE framework. It was Mr. Raymond's tenure at Exxon that cemented my favorable view of it.

The principles under which Mr. Raymond ran Exxon in the 1990s remain my core principles today: (1) guessing oil prices is neither possible nor the goal; rather it is to always invest in what will become the future low cost asset; (2) limit investment to projects that are or will be at the low end of the industry cost curve; any remaining cash flow should be returned to shareholders; (3) “AAA” balance sheet; (4) profitable at the trough of the cycle; (5) Being big is only an issue if you are not nimble; Big and nimble will crush small and nimble.

As a young analyst, I was scared to death of Mr. Raymond. He was an imposing, larger than life figure who did not suffer fools. I will say I always asked a question at analyst meetings and he always answered them without embarrassing me, which I took to be a sign my questions were not terrible.

We all knew Mr. Raymond was "God" and ran Exxon's famed "God Pod" with an iron fist. I recall an investor trip to China in the late 1990s where a bunch of us asked Exxon's China team why they weren't pursuing some highly sought after gas development project that all the other Majors were after. I can still recall the answer: "I am not going to be the person to go in front of Lee Raymond and explain why I invested in a low-return gas development in China that we will ultimately need to write down." The culture of profitability above all else had made it around the world in the pre-internet era.

With hindsight, I believe there are two critiques to the Lee Raymond legacy: (1) the insular, God Pod culture did not translate to continued success for ExxonMobil post Mr. Raymond's tenure; apparently not everyone can be God. (2) 1990s-era Exxon set the tone for how industry dealt with regulators, the general public, and environmentalists. That tone was dismissive, defensive, and insular. The relationship remains unhealthy to this day. That is not solely the fault of Mr. Raymond who has now been retired for nearly 20 years. But the seeds of the western world turning hostile to fossil fuels, I think, started in this time frame (i.e., the 1990s). It's unfair to lay the full weight of it on Mr. Raymond; but he was "God" and led the dominant company.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

📘Appendix: Definitions and Clarifications

The universe of traditional energy companies included in my CAPEX commentary include 66 past and present publicly-traded US, Canadian, and European major integrated oils, US and Canadian E&Ps, major US oil service companies, and US refiners.

Excellent post as always Arjun. So often professional analysts and investors, people who spend all their time analyzing energy companies, get caught up in the price fluctuations (it's an occupational hazard as the price is always in the headlines and always changing, whereas the core principles aren't in the headlines and don't change); we should always keep those core five principles in mind.

I find your posts thoroughly insightful.

One question: how useful do you think are portfolio optimization concepts like efficient frontier in the E&P world for companies to optimize their portfolio of assets in a given basin (or all of upstream) in order to avoid over capitalization?