Identifying Early ROCE Signals Ahead of Major Cycle Turns

ROCE Deep Dive Post #3: Bull steepening or bear flattening leads major inflections

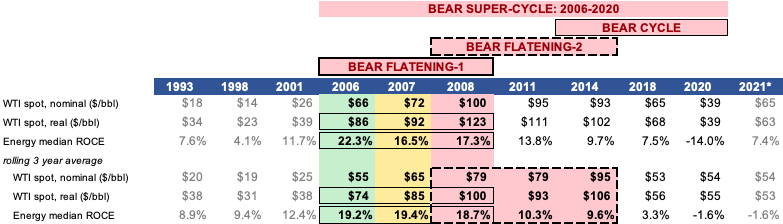

ROCE Deep Dive Post #3 highlights what I view as the most important early warning indicator that a major change in cycle is happening for the energy sector (or individual companies). In looking at the two structural ROCE eras of the last 30 years—1991-2006 UP and 2006-2020 DOWN (Exhibit 1)—there was a respective ROCE bull steepening and bear flattening that forewarned of the structural trend change. Most importantly, the early ROCE signal came ahead of the bigger oil macro call. I define bull steepening” (or “bear flattening”) to describe an improvement (or worsening) in ROCE for a given level of oil prices. For example, if ROCE rises to 10% from 7% at a flat $50/bbl oil price, that is a bull steepening. If ROCE fells to 7% from 10% at a flat $100 oil price, that is a bear flattening. I picked the terms “steepening” and “flattening” as it corresponds with how the dynamic reveals in a classic X-Y graph of oil prices (x-axis) versus ROCE (y-axis) (see Exhibits 2 and 3).

Specifically:

1993-2001 (BULL STEEPENING) saw ROCE improvement during a time of largely flat WTI oil prices, ahead of the major bull cycle of 2001-2006.

2006-2008 and 2010-2014 (BEAR FLATTENING) saw ROCE decline sharply despite a multi-year “$100 oil” environment, not a good sign. We have all since lived through the not-for-profit 2015-2020 era that followed.

In both eras, capital allocation was the most important consideration in driving the change in trend, followed by a sharp move up or down in oil prices.

In both periods, consensus was late in recognizing the change in trend—prematurely expecting a normalization back to the prior environment. This was especially true at the start of the Super-Spike era where bearishness persisted for much of the rally. During the past decade, the major shale equity issuance boom of 2015 suggested many investors (though not all) did not anticipate the failure of the Well IRR Drill-Baby-Drill model of Shale 1.0, which I discussed in ROCE Deep Dive Post #2 (here), and prematurely thought the worst was behind the sector. Perhaps most importantly, underlying ROCE led the oil macro.

Fast forward to today and the market is essentially in a “why bother” mode as poor returns and uncertainty about long-term oil demand trends given climate change concerns have relegated traditional energy to investor irrelevance. Even after taking into account significant 2021 outperformance, traditional energy is barely over 2.5% of the S&P 500 (Exhibit 4).

Looking back at history, I have used this framework to good effect in the 1990s and being early in calling the start of the Super-Spike era of 2004-2014. Unfortunately, I mis-interpreted the clear message being delivered in 2007 and 2008 and especially over 2010-2014 (the 2009 snapback I put in the “good call” bucket).

1991-2006 ROCE Bull Super-Cycle

As I highlighted in ROCE Deep Dive Post #1 (here), the 1990s were an interesting time for the energy sector. In nominal terms, WTI averaged between $14-$22/bbl on a full-year basis. Median ROCE for the Energy sector averaged a solid 9.0%. With the market broadly expecting a flat-to-bearish oil macro environment, companies were focused on cost cutting, asset/portfolio high-grading, and only investing in their highest return projects.

Bull steepening 1993 to 2001:

Bull steepening means ROCE was improving versus underlying oil prices.

In 2001, at $39/bbl real WTI ($26/bbl nominal), sector ROCE was 11.7%, a meaningful 4% higher than the 7.6% ROCE in 1993 seen at $34/bbl real WTI ($18/bbl nominal) price. Meaningfully better ROCE at only a slightly higher real oil price—a good sign.

Looking at 3-year rolling averages, $31/bbl average real oil prices over 1996-1998 yielded a 9.4% 3-year average ROCE, slightly higher than the 8.9% 3-year average ROCE over 1991-1993 at $38/bbl real WTI. Similar ROCE at lower real oil prices—a good sign.

By 2001, the 3-year average ROCE at $38/bbl real WTI was 12.4%, 3.5% higher than 1991-1993 at the same real WTI oil price. Meaningfully higher ROCE at the same real oil price—a good sign.

Major upcycle 2001-2006

As WTI oil prices rallied over 2003-2006, ROCE rose sharply, ultimately peaking at 22.3% in 2006 at $66/bbl nominal or $86/bbl real WTI. ROCE rose each year from 2003 through 2006.

The best part of this period is that industry executives and investors broadly did not anticipate an oil price super-cycle and therefore remained conservative in capital allocation.

From a big picture standpoint, it was a 15 year super-cycle from 1991 through 2006. Yes, there were many zigs and zags along the way for those with a shorter investment horizon. But the underlying trend supported ongoing relevance for the sector.

Spend some time on Exhibits 5 and 6, which show annual figures for WTI nominal, WTI real, and median Energy sector ROCE and then the corresponding rolling 3-year averages. In order to get the picture to fit legibaly, I have shown what I considered to be the most noteworthy individual years.

2006-2020 ROCE Bear Super-Cycle

While the past decade of poor performance is well known, I think very few remember 2006 as the ROCE cycle peak—with most incorrectly believing it must have been 2008 (or 2010-2014).

Bear flattening #1: 2006-2008

The numbers are really quite frightening. At $66/bbl nominal WTI, ROCE peaked at 22.3% in 2006 and then FELL to 17.3% in 2008 at $100/bbl nominal WTI. Using real WTI of $86/bbl and $123/bbl, respectively should not make anyone feel any better. Let that sink in: at much HIGHER oil prices in 2008, sector ROCE was LOWER than 2006.

One could argue (as I did at the time) that 17.3% was still a very good ROCE, which was true. And if ROCE had remained in the mid-teens, I suppose the sector might still be 10%+ of the S&P 500. But that is not what happened.

Bear flattening #2: 2011-2014

ROCE over 2011-2014 was 10.6% on average, slightly better than an 8%-10% industry “cost of capital”. However, especially relative to an average $95/bbl nominal or $107/bbl real WTI, these are not good figures.

Notably, the shale revolution had begun and led to a burst of non-OPEC supply that ultimately overwhelmed steady oil demand growth.

An early sign that Shale 1.0 was not going to prove to be very profitable is revealed in the decidedly mediocre industry ROCE in what was generally a “$100 oil” environment.

We all know how ROCE fell off a cliff with the late 2014/2015 WTI crash, setting off five years of absolute misery for the sector.

Looking ahead: Some good signs especially on the capital allocation front

Admittedly with 30 years of ROCE history and performance data, one can point out the longer-term trends with absolute confidence. I am currently on record in declaring that 2020 was the end of a 15-year down-cycle and that a new era of ROCE improvement has begun.

If we look at the first nine months of 2021, nominal WTI averaged $65/bbl, the same as in 2018. In both periods, ROCE was essentially 7.5%. Using real WTI paints a somewhat more encouraging picture with flat ROCE despite $5/bbl lower real WTI. While demonstrated ROCE suggests the bleeding has indeed stopped, my greater optimism about the future comes from the dramatic declines in reinvestment rates and much-improved capital allocation framework most of the sector is employing. Time will tell if this holds and translates to better ROCE as I expect.

ROCE vs oil prices: ROCE is king in equity analysis

Its easy to over-analyze oil prices as the key sector driver. I have never believed this, even when at times I have been especially well-known for a high profile oil macro call. As an equity analyst first and foremost, it is always about returns on capital—oil prices are just one, albeit important, variable. As the last 30 years reveal, oil prices are often relevant for year-to-year (i.e., shorter term) trading realities. But I would argue that solely focusing on oil prices was not as helpful over most longer periods of time.

Start-up companies might get a pass on adequate ROCE in the early years as they are building a business. In the oil business, as an example, early play entrants can reap differential gains by recognizing “sweet spots” ahead of competitors. Given the lag from acreage acquisition and exploration drilling to full field development can be many years, a lack of adequate ROCE is not unreasonable in the early years. Ultimately, however, profits have to follow.

For larger companies, there is usually not very many good reasons for weak ROCE. Full stop. One might forgive an extreme cyclical downturn caused by say a once in a hundred years pandemic. However, the decade of pre-pandemic poor ROCE is harder to forgive. An excellent goal for larger companies is to generate “cost of capital” ROCE (8%-10%) at cycle troughs. Best-in-class “buy and hold” companies have demonstrated this capability.

There is no substitute for profitability. It is the only reason a corporation exists—and with those profits shareholders, employees, and citizens ultimately benefit. If those groups don’t benefit from profitable companies, regulation/laws exist to counter negative externalities or corporate excess. As I have said before, a belief in limited government is not support for anarchy. Thank goodness for the Clean Air Act, CARB gasoline, and anti-trust laws, among many other useful constraints on unfettered capitalism. What we don’t need is socialism; as you know, I am pro capitalism, anti socialism.

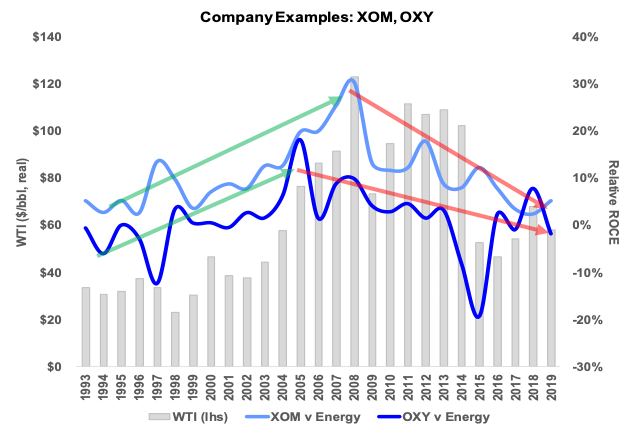

This framework can be used at the company level

I will elaborate more on the company-specific application of the bull steepening versus bear flattening framework in a future “Dumb Calls I Made as a Street Analyst” post. But two companies I have previously written about fit the bill: Occidental Petroleum (OXY) which I got wrong and ExxonMobil (XOM) where my call was better.

In the case of OXY, I wrote in Dumb Calls Post #1 (here) how I was incorrectly bearish on OXY ahead of major ROCE improvement. Unfortunately, I turned bullish on it at a time that ROCE was turning down, both on an absolute basis and relative to the sector.

For XOM, I was not a fan of the 2009 acquisition of XTO Energy, which proved proficient in anticipating a major erosion in its famed ROCE advantage. As bearish as I was on XTO, the next decade was actually much worse for XOM than even I expected. For both OXY and XOM, the key line to focus on is the company’s ROCE relative to the sector in Exhibit 7.

On a personal note…

On Christmas Day, I had the opportunity to test the “auto pilot” (I prefer Tesla’s marketing terms) in our family’s 2020 BMW X5; I normally drive a 2020 Tesla Model 3. While the X5 is indeed a beautiful medium-sized SUV, the driver assist functionality leaves a lot to be desired versus the Model 3. I don’t think it is a close call. Fortunately I am a fairly cautious user of driver assist features, doing my best to stay focused on the road ahead and ready to re-engage if need be. With the BMW, the need arose regularly. I didn’t think it was anywhere near as good as where Tesla is on the technology.

Tesla also gave me a nice holiday software update with a refreshed UI on its “iPad” interface. I love the ability to pick and choose my primary apps. I am in Year 7 as a super happy Tesla driver; I especially enjoy how my Model 3 (and previous Model S) get these software updates that make the car feel new and improved. As I have said many times, while I believe global oil demand will grow at least through 2030 and possibly 2035, I will personally never go back to having an ICE vehicle as my primary ride. For the Christmas travel, I was chauffeuring a larger number of passengers than could comfortably fit in the Model 3. Next time we might need to have our golden doodle enjoy a play date with our local sitter so we can take the Model 3.

Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Appendix A: Previous Posts in “ROCE Deep Dive” and “Dumb Calls I Made as a Street Analyst” series

ROCE Deep Dive Post #1 (December 7, 2021)

ROCE Deep Dive Post #2 (December 12, 2021)

Dumb Calls I Made as a Street Analyst Post #1 (December 18, 2021)

Appendix B: Definitions and Clarifications

All data is from Bloomberg and S&P Capital IQ. I have done my best to ensure the underlying quality of the data, but readers should not rely on it for precise accuracy and should verify by doing their own work. At Goldman, JPMIM, and Petrie, I used my own proprietary company and industry models for analysis like what is presented in this post. My models in those days were sourced primarily from SEC and other company/industry filings. While I still maintain a handful of company models, I no longer do this at the industry level, relying instead on third part data providers. I also no longer have a team of colleagues to help ensure data quality.

Real WTI oil prices are in 2020 US$.

As always, ROCE is on an “as reported” basis and not adjusted for the infinite items analysts focused on shorter time horizons might choose to ignore.

Fantastic posts - all three ROCE deep dives!

is the difference between real and nominal wti price adjusting for inflation? if so, how do u calculate real wti? which year is the baseline u compare against?