Scope 3, as currently defined, is a societal cop-out

We could use less virtue signaling, more pragmatism in dealing with CO2 emissions

This is the fourth note in my series on how the traditional oil & gas sector should think about energy transition resilience. But it takes a different tone from the previous two. I’ll start with the punch-line. Scope 3, as currently defined, is a societal cop-out on dealing with carbon emissions. The notion that we need to make “Big (and Small) Oil clean up their mess”, I predict, will fail as an approach, if the goal is to eliminate both energy poverty and net carbon emissions. This note is not about ideology or signaling virtue or defending fossil fuel interests or whether any of us love or hate Big (or Small) Oil. I am only interested in figuring out how we can eliminate energy poverty with as small of a carbon and environmental footprint as possible.

The great progress that has been made on the energy poverty reduction side of the equation is at risk from a messy energy transition era being driven by public policy and certain ESG initiatives trying to solve solely for the carbon emissions side of things. It is my motivation in creating Super-Spiked. As I have said many times now, you will never solve climate without first, or simultaneously, ending energy poverty and ensuring everyone on Earth has access to abundant, affordable, reliable, secure energy supply.

Energy supply is not a typical consumer/business product

The idea that energy supply (all of it, not just fossil fuels), which is essential to modern human life and has contributed to massive improvements in life expectancy, quality of life, poverty reduction, and environmental improvements, should be treated like any other consumer or business product in terms of end use liabilities is absurd at face value. If you create an autonomous driving technology that directly leads to accidents, that is a problem in need of regulation or other fixes. If you create a drug or food product that sickens people, that is a problem in need of regulation or other fixes. If you promise people that your new exercise program will extend a user’s life by 25 years without proof, that is not an acceptable thing to do and should be prohibited.

These examples, in my humble opinion, is not how we should think about energy supply, be it from fossil fuels, nuclear, renewables, or biomass. Energy is life. We all need abundant, affordable, secure energy supply to live longer, to have cleaner air and water, and to live the best lives that we can. Unfortunately, the average African consumes less electricity per year than a typical American family’s refrigerator (source), and perhaps as many as 1 billion people currently do without any form of modern (i.e., non-biomass) energy. “100% renewables” has precisely zero chance of adequately addressing the energy needs of those people. The outcomes for that population will be significantly enhanced with greater access to modern energy of any form (fossil or nuclear or renewable). And to be clear, I am in favor of meaningful renewables growth; all forms of energy supply are welcome and needed.

At the same time, we have a negative externality—too much carbon—that comes from combusting fossil fuels like coal, crude oil, and natural gas. Asking/demanding/ requiring/regulating oil companies to fix the negative externality by eliminating their Scope 3 emissions (i.e., the end use of their product) is the same thing as saying “we don’t really understand the nature of energy, how and why we use it, the pros and cons of different technologies, or the timing and complexity of a massive and needed evolution in how we energize the world; we simply want to score political or ideological victories against an easy target.”

The idea that you are going to shift the circa 85% of primary fuels from fossil to non-fossil within 30 years, or any longer or shorter time frame, while, mind you, we are not ramping and perhaps even shutting down nuclear power, is as big of a mis-information campaign as anything produced by a 1980s era major oil company. I know, there are some super smart Ivory Tower elites that have modeled that it is theoretically possible. Tell that to the impoverished in the developing world. Tell it to the struggling middle and working classes in the western world set to experience a sustained energy price shock. Global elites can not and will not solve this problem. They are the problem (and not just in energy of course).

But Arjun, take away the extreme rhetoric: Isn’t Big Oil hindering progress on even incremental solutions in order to protect their interests and shouldn’t they “do their part” to help regardless of exactly how we allocate blame for too much carbon? I would encourage everyone that cares about energy and climate to spend 12 months as an energy equity research analyst. The oil industry hasn’t generated meaningful profits since before 2010. There are no profits to protect! They are a business and the last time I checked, every business on Earth seeks to defend its interests. That is not unique to the oil industry. The oil industry is barely 3% of the S&P 500 down from 12%-15% a decade ago, and similarly eroded in corresponding global benchmarks like the FTSE and MSCI. Big Oil is no longer especially relevant to investors! Heck, they are barely relevant to the oil industry. Why would anyone think an irrelevant, barely profitable commodity sector is the key to solving an intractable negative externality like carbon emissions? That is a bad joke even the Babylon Bee wouldn’t dare write (disclosure: I am big fan of the Bee).

It is true that profitability is improving and I believe we are at the start of a potentially decade-long return on capital super cycle for traditional energy. It is incumbent on the oil & gas sector going forward to proactively engage on climate and energy in order to remain relevant to investors and ensure a sustainable business beyond this coming decade. It is my view, however, that Scope 3 mandates, be it via public policy or, more likely, ESG extremists, is precisely the wrong way to solve society’s dual challenge of eliminating energy poverty with as small of a carbon and environmental footprint as possible.

What are we potentially on-track for? We all end up like Europe—a great place to vacation and study history but a bad place to emulate from an energy policy perspective. I will be eternally grateful that in 1961 my parents emigrated from India to the United State and not Europe as they might have. Everyone needs abundant, available and secure energy and all but the most affluent need it to be affordable. If you do not solve for that first or understand that, you will never solve our carbon emissions problem.

Killing oil demand requires hard public policy choices no one wants to make

What is the objective here? It is to de-link economic growth from fossil fuel growth. We have not done so to date. Fossil fuels do grow at about half the rate of global GDP, but is still very much positively correlated. Before you even talk about decreasing fossil fuel demand within the context of positive global GDP growth, the first step is to de-link the two. Plateau comes first, then decline. Right now we continue to have upward sloping, positively correlated growth.

Here are two straightforward short-term steps I propose that unfortunately have near zero chance of happening but in my view would actually start the process of de-linking oil demand growth from global GDP growth:

Ban SUVs (i.e., reform Corporate Average Fuel Economy, CAFE, standards). Governments can exempt farmers and retain the option for large families to drive mini-vans. After all, I am pro family formation and pro-capitalism; I am anti-Malthusian, de-growth pessimism and anti-socialism.

Lower the maximum speed limit to 55 mph (long-time Super-Spiked subscribers over the age of 45 know what's coming at the end of this note!)

The fact that there is no chance of the clearly needed steps being taken is why I believe oil demand will grow at least through 2030. That is not a wish or a desire. I am neither an advocate nor an activist. I am an equity research analyst (and senior advisor and board member) trying to figure out the macro trends that are actually going to happen. In this instance, I am providing suggestions on how to change the trend (ban SUVs, drive 55) as well as what won't change the trend (demonizing Big Oil).

Excluding recession, the only way crude oil demand actually plateaus let alone falls THIS decade is if we achieve the step-change in efficiency gains that are predicated in current net zero pathways articulated by the IEA, BP, Shell, other Ivory Tower global elites, and many others. At this moment, there is zero evidence that a step-change improvement in efficiency is on-track to happen—none, nada, zero, zip. The overwhelming reasons for the miss are:

the SUV-ification of the world's ICE vehicle fleet;

the fact that used cars don't die, they simply get handed down to increasingly lower income consumers;

real world driving is a far cry from laboratory "sticker" mpg driving;

cars experience decreasing fuel economy as they age.

The world has missed circa 80%-90% of its fuel economy improvement objectives over the past 20 years. It's not a close call. I don't understand the lazy analytics that simply dial in government promises on a go forward basis.

It's got nothing to do with Republicans or Democrats or Trump or Biden or Bush or Obama or Autocrats or Xi or Putin or Socialists (ex-Europe, which has had success on this metric) or Big Oil lobbying or even Big Auto lobbying for that matter. It's fully and totally about consumer preference and an unwillingness or inability for global public policy to address it. If you don't like the choices being made, public policy will have to forcibly stop it or you should resign yourself to continued oil demand growth. That is the choice. There is no other choice.

EVs are indeed coming, but basic math will tell you that in the best case EVs will drive a moderation in post 2030 oil demand growth; even on that, we shall see. If it isn’t already clear, that view reflects a pessimism on fuel economy gains, not EVs. And for those of you that are new Super-Spiked readers, I have driven a Tesla for the past six years and will never ever again own an ICE vehicle as my primary ride; I am bullish EVs, in theory. I am also a retired partner of Goldman Sachs and not a person in the middle/working class or someone dependent on burning biomass in the developing world. I am super lucky.

Fuel economy gains in the USA have badly lagged the 2%-3% improvement that would be required to de-link demand growth from GDP growth.

Globally, there is no evidence of a step-change improvement in efficiency gains that would similarly lead one to believe global oil demand was about to roll over.

Scope 3, as currently defined, is simply performative virtue signaling rubbish

The idea that Big Oil, or any sized oil for that matter, can have any impact on how many Amazon delivery trucks are endlessly circling our neighborhoods, how many Chevy Suburbans are driven by stay-at-home parents to their pilates classes or local bar, and the failure to properly calibrate CAFE standards with actual results is simply preposterous. Anyone with any modicum of common sense living outside of an Ivory Tower understands this. You can love or hate Big Oil; it doesn't matter. It's completely irrelevant if what you care about is decreasing carbon emissions.

Scope 3 as currently defined is a bad joke perpetrated on the masses in order to shift responsibility from host governments and consumers onto an easy target: Evil Big Oil. I am not arguing that Big Oil is good or evil. It's simply not a relevant point on the core mission and really an insidious mis-direct. What evidence is there that the "Big Oil Is The New Big Tobacco" playbook being pursued by climate enthusiasts has decreased carbon emissions by a single metric tonne?

Similarly, there is no chance a single vote be Senators Manchin or Sinema will make any meaningful difference on our ultimate carbon trajectory when we know that the underlying analysis is rotten to the core (to be clear, I am referring to broad-based analyses, not necessarily the analysis for this particular bill though that could well be true also). Yes, there are some good clean energy incentives in Build Back Better. But there are also some pretty bad ideas. And whatever that mix of good or bad actually turns out to be, if we are not doing the easy stuff like reforming CAFE, why do we think will be better at the harder stuff?

What about the handful of oil companies with Scope 3 reduction targets? Either they will be ultimately exiting the oil and gas business (which has zero impact on oil and gas demand and therefore emissions) or the math leaves as much to be desired as the world’s fuel economy gain calculations.

How could Scope 3 be reformed?

Since we know suburban western world parents will not be driving mini-vans en masse, and we know the ability to drive 55 (or less) hasn't improved since Sammy's 1984 rallying cry, and we know that tough public policy choices aren't being made anywhere in the world that I can see (leaving Europe aside again), it seems that there will remain pressure to have industries deal with societal emissions. Indirect taxation is so much better than the direct version if you are a politician.

Right now, Scope 3 is about 10X Scopes 1 and 2 for most oil companies (round numbers here). That is why climate enthusiasts view it as the whole ball game in terms of carbon emission reduction. In this respect, the climate crowd is correct in their math, but wrong in attribution. Scope 3 is the world we live in today. All of it.

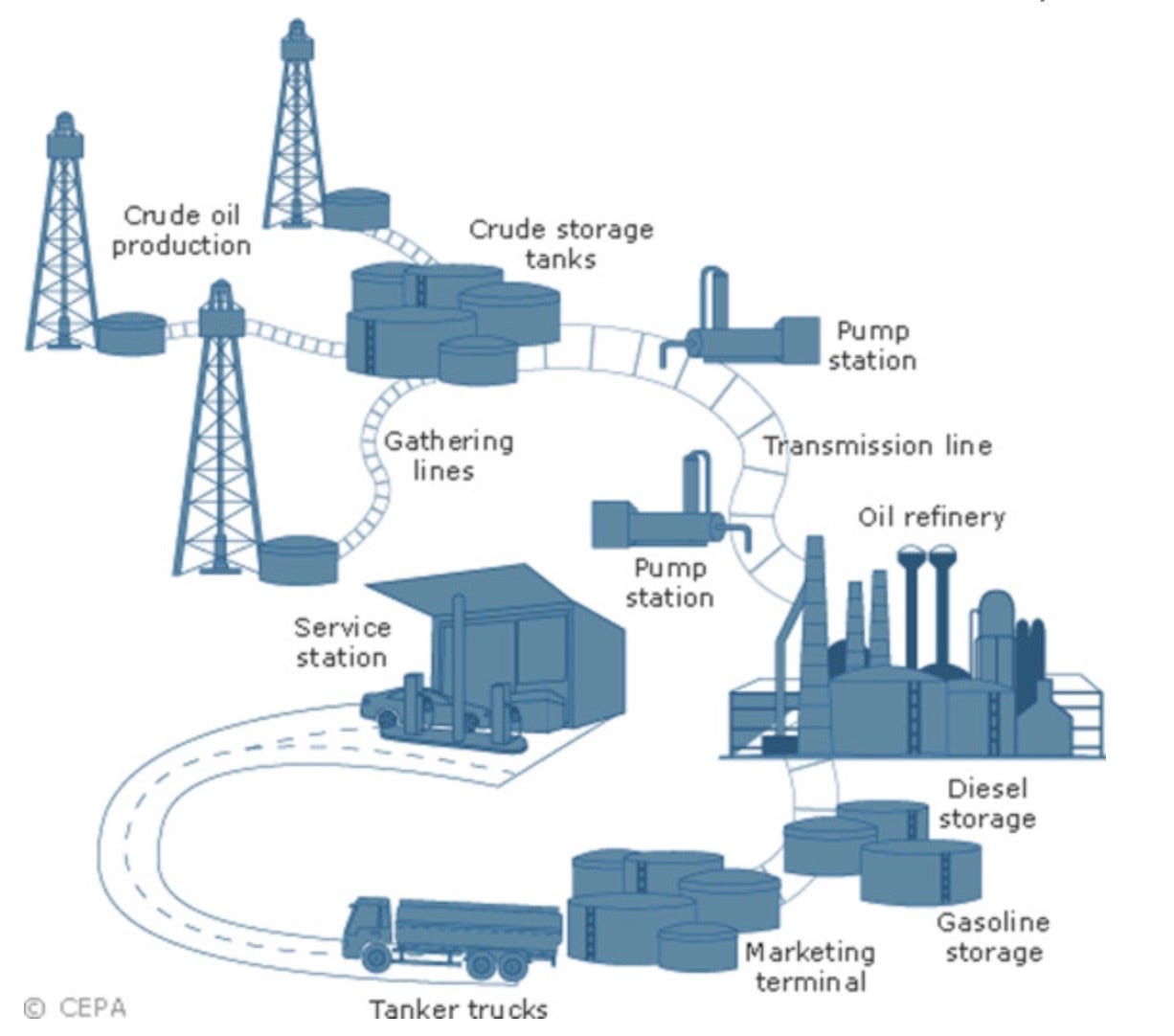

Scope 3 as currently defined is repeated over and over again within sub-sectors and companies. As a simple example, an E&P company will typically offload its crude oil to a gathering company which then offloads it to a pipeline company which then delivers it to a refinery which then delivers it to a refined product wholesaler which then delivers it to an end-use outlet like a gas station. Just in that simplified version of the value chain, we could have as much as a 7X-overcounting of Scope 3. If one excludes the portions of that chain where ownership of the barrel doesn’t change hands, this is probably down to a triple or quadruple over-count. The crude oil is then actually combusted as gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel by the Chevy Suburban, Amazon Prime delivery truck, or a United Airlines thrice-delayed flight. No one that passed basic Algebra can think such an accounting makes any sense.

The question that I am not in a position to answer at this moment is how best to allocate Scope 3 between the oil producer, the refiner, the gas station, Chevrolet, Amazon or United. It is really hard for me to not think that banning SUVs and same day delivery (if using an ICE vehicle) isn't simply easier if it is carbon emissions you are solving for. Frankly, United Airlines is the only one in this group making any effort to reduce society’s “Scope 3” use of fossil fuels by regularly cancelling flights (mild joke; I do like their app better than other US airlines). I would welcome suggestions on a proper methodology to allocate Scope 3 emissions among business sectors; I do not believe the correct split is 600% to the oil industry, 0% to consumers, and fuzzy math on all others.

Said another way, there could well be a role for the oil industry to play here. But as I articulated earlier, treating energy supply like any other consumer or business product is not grounded in a reality that will ensure sensible energy policy prevails. Mandating Big Oil “get on board with Scope 3” as currently defined, is bad math, societally irresponsible, and a fool’s errand.

Energy value chain: Scope 3 has the potential to be over-counted many, many times across the value chain

Mis-information comes from everyone and everywhere

I would like to spend a moment on the important topic of mis-information. I agree that there is and has been a lot of mis-information from all sides when it comes to energy supply and carbon emissions, another key motivation to creating Super-Spiked. There is little doubt that the oil industry has been slow to address methane mitigation as an example (discussed below). In previous decades, it is likely that certain oil companies (large and small) contributed to climate mis-information campaigns, which is troubling and unfortunate.

But there is a corresponding mis-information campaign from climate enthusiasts today. There is no chance the we can sustain and grow the modern world with “100% renewables” within any reasonable time frame. Certainly not within the next 30 years. It’s not a close call. No form of energy supply, let alone region, let alone project area in any absolute sense is ever the most or least expensive.

To use an oil industry example, no one can declare the Permian Basin or even Saudi Arabia is the low cost area. Some parts, the sweet spots still to be developed, are indeed very low cost. Other parts are medium cost and still others are high cost. This is going to be true with every form of energy supply, including renewables.

You do not need to be an energy expert, in fact it probably helps to not be one, to recognize that it is absolute malfeasance to suggest we can or would want to be 100% of any form of supply. Certainly not intermittent renewables. If it is indeed an existential climate crisis (their words, not mine; I am much closer to Michael Shellenberger’s Apocalyspe Never view of the world) that needs to be urgently addressed, why wouldn’t the world undertake a massive nuclear build out until the combination of renewables and battery storage could lead to abundant, reliable, affordable, secure energy?

And let me be clear, I support growth in renewables. I view it as an interesting, major growth area for investors. Adding new energy supply that has zero variable cost (when working) is a great thing. But supporting efforts to make renewables the 100% solution for future electricity supply is simply non-sensical public policy that is particularly damaging to the world’s non-affluent. Prematurely retiring energy supply that delivers abundant, affordable, secure energy BEFORE the new stuff is fully ready for prime time is a crime against humanity.

What climate responsibility does the oil & gas industry bear? Methane is #1

The biggest potential climate victory that is within grasp—it is actually reasonably low hanging fruit today!—is eliminating routine flaring, venting and fixing the preponderance of meaningful methane leaks. I will guess that the global LNG industry will figure this out first for future projects. The US shale industry should be right behind it, right now, not five or three years from now.

As I understand it, methane regulations ordered executively by the Obama Administration were heavy handed and ill-advised in the sense that they would have had little impact on methane emissions but would have been costly to industry (I believe moderate environmentalists would agree with this point). The fortuitous outcome, however, was that it forced oil companies to study more deeply the issue of addressing methane. At the same time, technologies like drone surveillance and cloud computing have progressed to a point that identifying, measuring, and addressing methane is significantly progressed from what existed in the mid-2015s time frame.

I am simplifying a complex issue in order to keep the note readable, but I no longer see cost or technology as inhibiting industry from dealing with the preponderance of eliminating methane from spilling into the atmosphere. Leading companies have made what I consider to be sincere, good faith promises to address methane at their companies. It is a start but I strongly suspect won't sufficiently solve the problem. I believe a broader industry solution is needed to ensure smaller or otherwise less responsible producers and especially midstream companies are aligned and taking needed action. For example, if a large producer is non-operated in some areas or doesn't control midstream or pipeline infrastructure in another, it is hardly clear to me that we can be certain methane leaks and venting will be (overwhelmingly) eliminated. Industry-wide "regulation" is needed; preferably self-regulation from a trade group. If that doesn't happen, I would guess it would need to be externally regulated.

Ultimately, oil & gas methane is a global issue. I believe future LNG projects have a decent chance to be methane venting/leak free given the limited number of buyers and sellers and the unique combination of responsible Big Oils (that is not an oxymoron for those of you in the climate crowd reading this) and major country buy-side purchasers. I actually think Middle East producers like Qatar, UAE, and Saudi Arabia could become early leaders on addressing methane. Other regions like Russia, Iraq, Iran, and Kazakhstan will need to get on board, but no one expects to be early adopters. The competition for “cleanest barrel or MCF in the world” has started; oil & gas companies and countries that do not recognize the race is underway risk being roadkill in the energy transition. I will expand on this theme in a future posts.

Do other industries like agriculture also need to address methane? Sure. But I don't see what that has to do with the oil and gas industry. As an equity research analyst covering the energy space, I don't personally care (in my professional capacity) what agriculture is doing or not doing, and I don't think my former institutional equity investor client base cares either; Ag is not a determinant on whether traditional oil and gas is worthy of investment going forward.

I will also say that I agree with climate enthusiasts on one important additional point. If the oil and gas industry can not show how it is handling the methane issue, we can not be certain about the degree to which natural gas is better than coal in terms of its overall emissions profile. In my view, that was the point most missing in what was otherwise an excellent letter from EQT CEO Toby Rice to Senator Elizabeth Warren (here). I still believe that natural gas will be a critical future source of energy supply, especially for the developing world. But the oil & gas industry needs to better document that it is indeed distinctly better than coal, inclusive of methane, from an emissions standpoint.

Net Zero Scope 1 and 2 are now table stakes within my energy transition resilience framework

I support net zero Scope 1 and 2 emissions objectives for all industries by some year, presumably 2050. The fact that a certain Super Major that shall go nameless and no one will figure out didn't announce such an objective until January 18, 2022 is, frankly, shocking and a sign that the oil and gas industry has been poorly led in terms of constructive climate engagement strategies by its long-standing (1870-2010), formerly best-in-class global leader. It is what it is. The entire rest of industry needs to look forward and find new leadership.

For climate enthusiasts, I would humbly offer that I believe you are wasting your own energy and resources overly focusing on any one Super Major; they simply don’t matter as much to the sector or to the world as they once did. I suggest you move on. Most investors have. There is one notable new investment firm that is trying to constructively engage to make that company better; I broadly support what I perceive to be the intentions of their efforts and believe they have a fighter’s chance of succeeding.

I have discussed other elements of my energy transition resilience framework for oil & gas companies in previous notes (here, here, and here). I would note that investing in low carbon opportunities can make sense for oil & gas companies. I support the steps some companies have taken to evaluate opportunities in areas like CCUS, direct air capture, hydrogen, and renewable fuels, among others (not a complete list). What I am arguing against in this post is the idea that there needs to be a mandate that forces oil & gas companies to transition to new technologies where they do not have a competitive advantage. That makes no sense.

Energy Flux podcast appearance: “Why ESG & climate policies are good for oil companies”

If you would like to hear what is in essence an audio version of this note, I recently joined Seb Kennedy’s Energy Flux podcast to discuss “Why ESG & climate polices are good for oil companies” (listen here). I would also refer you to his excellent Substack (here).

On a personal note

My subscriber list has grown so I’ll repeat something early readers already know: I welcome constructive feedback, dialogue, and debate on any point I make. I have documented in prior posts at least some of the wrong calls I made during my analyst career (here). I know I will make wrong calls in the future, including, possibly, within this note. If you disagree, don’t like, or otherwise have differing views, please argue back on the fundamental points. I do miss the institutional investor client pushback/feedback I used to get on my calls when I was a publishing Goldman analyst, so please engage on the fundamental points.

And whatever you don’t like about my views, blame me, not any current or past affiliation. I don’t work full-time anymore and this post is for free (yes, I am super lucky; I do receive compensation from one advisory role and one board position, the latter of which is public). Anyone can easily look up my affiliations that some will argue create real or perceived conflicts of interest. I attest that these are my strongly held personal views at the time of this writing.

I have noticed a tendency from a very small minority of social media users, usually from those especially passionate about climate, that tend toward personal/character attacks rather than arguing the fundamental points. The only personal attacks that could have a notable effect on me would come from my immediate family; I value their opinion of my personal character. The biases I do have include that I am proudly American, pro-capitalism, and anti-socialism.

Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Appendix A: Definitions and Clarifications

The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard classifies a company’s GHG emissions into three “scopes”.

Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources.

Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy.

Scope 3 emissions are all indirect emissions (not included in scope 2) that occur in the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream emissions.

To be clear, I believe this protocol would benefit from some updating; I include it here for any readers unfamiliar with the various “scopes”.

US fuel economy exhibit. Measures annual precent change in miles per gallon in the USA. The two grey bars at 2%-3% show CAFE objectives as well as what would be required to de-link gasoline (and overall crude oil) demand growth with GDP growth.

Global oil demand efficiency gains exhibit. The intention of the graph is to measure the annual efficiency gain in global oil demand relative to global GDP growth. In my view, there is a “normal” year-in, year-out efficiency gain that happens. In order to de-link global oil demand from global GDP growth, this rate of efficiency essentially needs to at least double from current levels. So far, there is no evidence that is on-track to happen.

Appendix B: Super-Spiked energy transition playlist

Sammy Hagar's classic from a prior era's attempt at fuel economy gains is the fifth addition to the Super-Spiked energy transition playlist. I actually forgot last week about Wolf Hoffman's masterpiece that I include as my intro/outro on the YouTube Videopods. I don't think the Sammy video needs any further commentary. Enjoy. It is an all-time classic.

Super-Spiked energy transition playlist

1. Concert for 2 Cellos in G Minor, RV 531: I. Allegro Moderato. Given Germany is at the center of energy transition policy controversy, it seemed appropriate to use this song from Wolf Hoffman, lead guitarist of Accept, as the intro/outro for Super-Spiked Videopods.

2. Whiplash. Energy transition is driving a new era of commodity price volatility.

3. Amazonia. All of us here at Super-Spiked (i.e, me) are on board with saving the Amazon Rain Forest and being more respectful of Indigenous Peoples.

4. Creeping Death. Signifies the risk of decreasing capital market access for companies that ignore substantive ESG principles.

5. I Can't Drive 55. A step change in fuel economy is the key for oil demand moderation this decade, but doesn't seem on-track to happen. Apparently no one outside of Europe and perhaps Japan can drive 55.