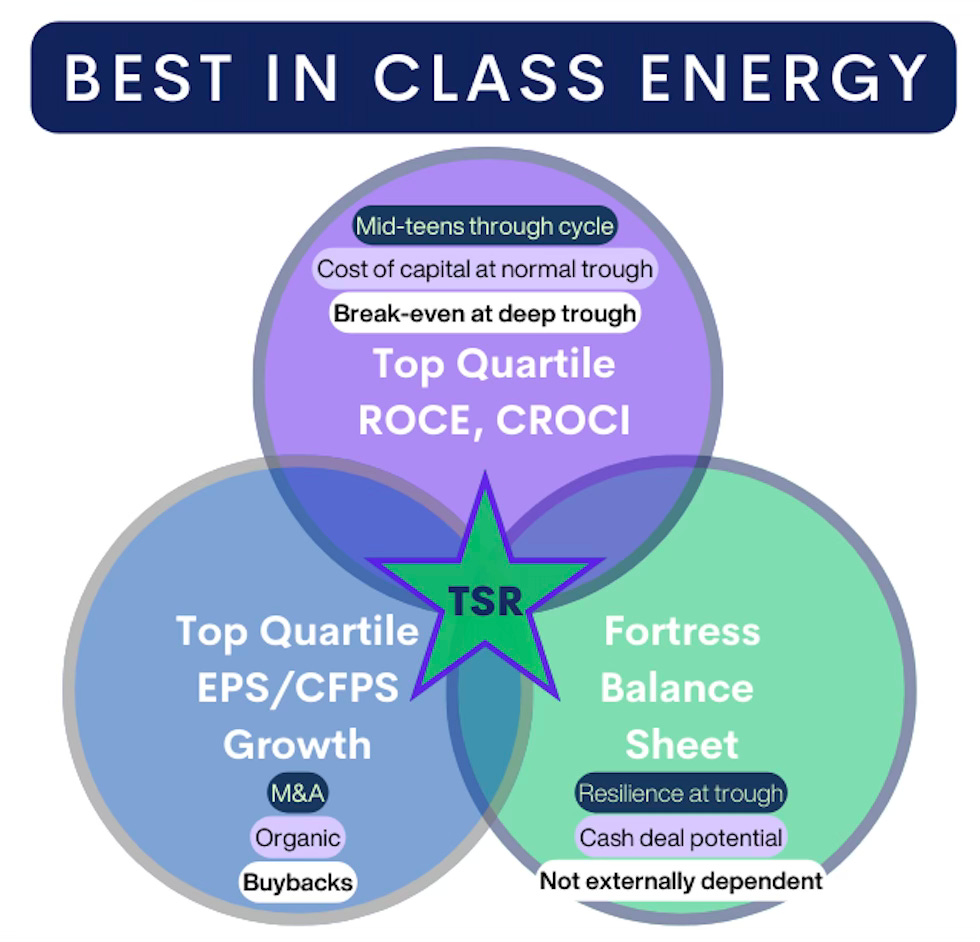

Stocks move with earnings is an age-old Wall Street adage. As goes EPS revisions, so goes underlying equities. For commodity equities, as goes commodity prices so goes commodity equities is similarly tried-and-true. The latter certainly works in the short-term. But over the longer-run, we see meaningful differences for companies that hit the trifecta of leading profitability, leading EPS/CFPS growth, and a healthy balance sheet that provides resilience and opportunity during commodity price downturns (Exhibit 1). The challenge for management teams is to do better than the underlying commodity price/margin over a full cycle; commodity prices by definition will move up and down over time but yield a cost-of-capital return for the sector overall for the capital invested to generate supply that matches demand.

Exhibit 1: Characteristics of Long-Term Energy Equity Outperformance

Source: Veriten.

The Long-Term vs Short-Term EPS/CPFS Revisions Cycle

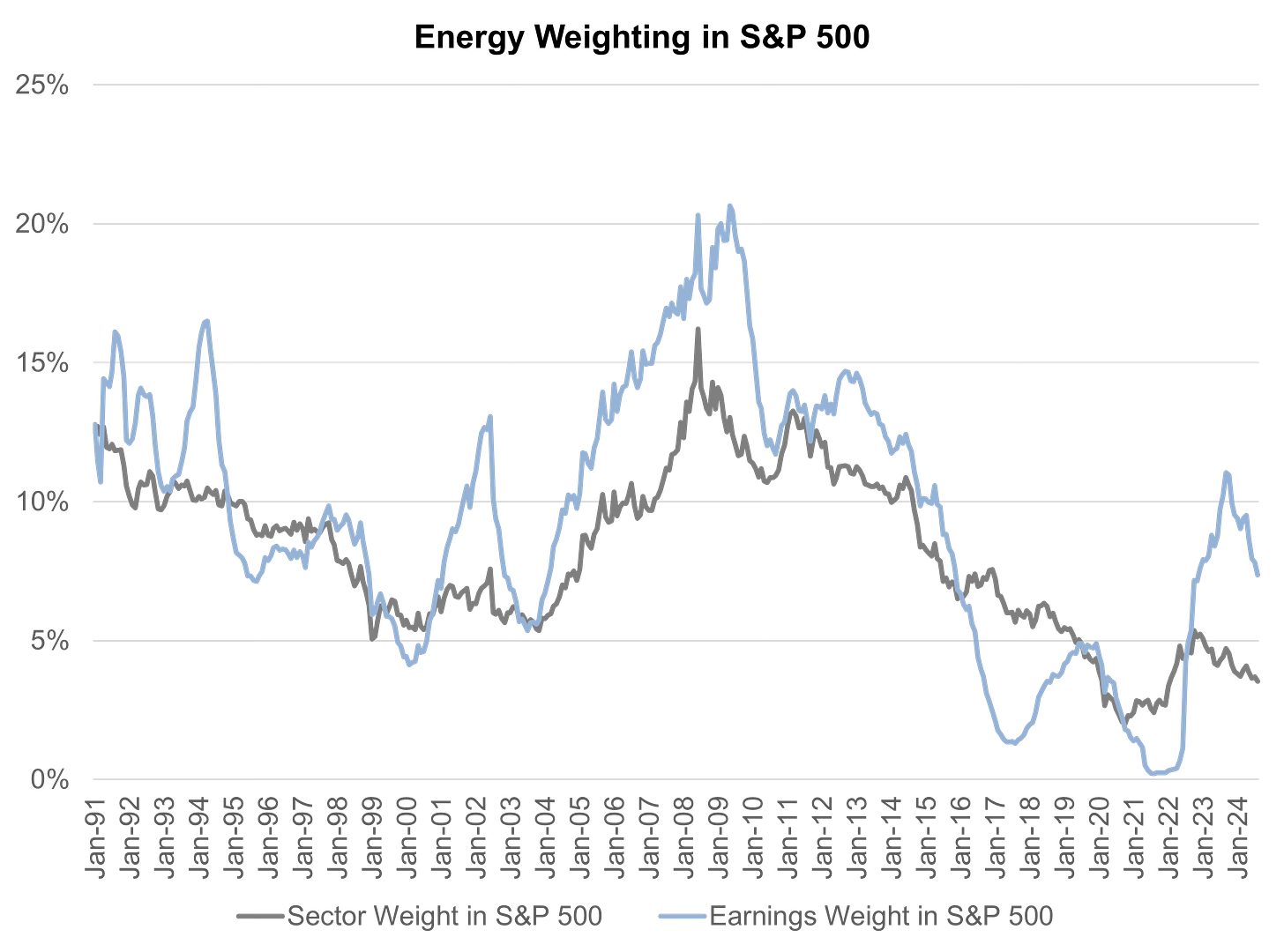

We have regularly shown Exhibit 2 to indicate energy was under-punching its earnings weight in the S&P 500, meaning the sector appeared inexpensive given that its market capitalization weighting was below what would be implied by its earnings contribution. This remains the case.

Exhibit 2: Energy’s S&P weighting moves with its earnings performance relative to the S&P 500; Energy looks inexpensive but is in a negative EPS revisions cycle

Source: FactSet, Veriten.

But we have also noted that since the 2022 Russia-Ukraine peak in crude oil, natural gas (US and global), and refining prices/margins, the sector has been in an extended negative earnings revision cycle—an annoyingly slow drip of downward adjustments. Moreover, with crude oil prices below peak but above likely trough levels, investor sentiment has been caught in the no-mans-land of not being at an extreme while facing EPS revision headwinds and concerns over soft global economic conditions, especially in China—a potent recipe for investor avoidance.

For the purposes of this post, we are going to treat EPS (earnings per share) and CFPS (cash flow per share) as interchangeable (we also use the term “earnings” as interchangeable with EPS and CFPS). EPS revisions would be the metric a generalist investor is likely to most focus on. We highlight CFPS to focus on underlying cash generation and to eliminate the noise of write-offs and related accounting adjustments, but the trends are identical.

Characteristics of companies with superior EPS/CFPS growth

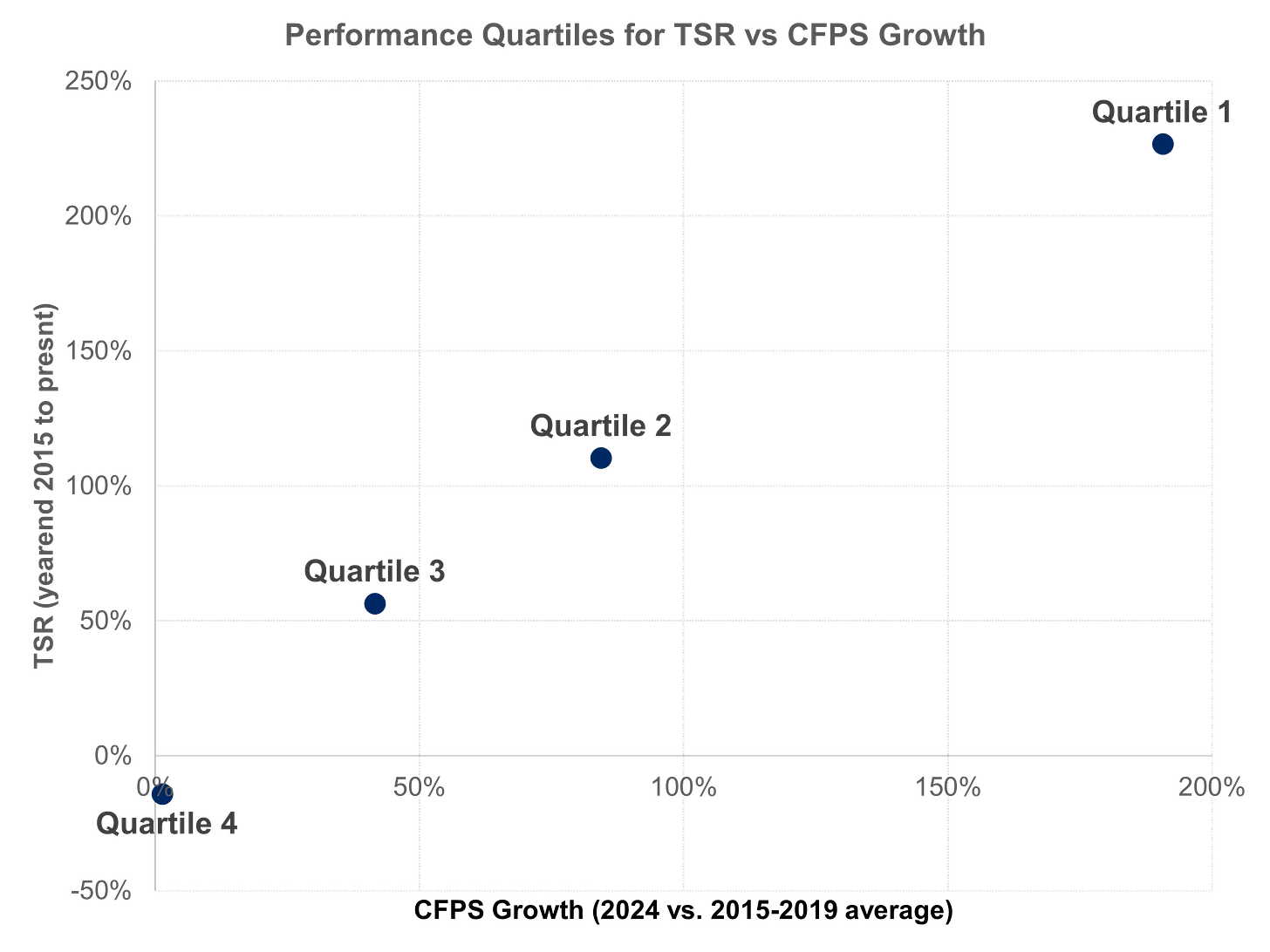

We have looked at a universe of 35 companies that span the Majors (US and European), E&Ps (US and Canadian), and downstream (US) sectors to evaluate the attributes of what drove outperformance over the last decade (Exhibit 3). We need to do more work scrubbing our midstream and oil services analysis before including those sectors as well.

Exhibit 3: Higher TSR correlates with higher CFPS growth

Source: FactSet, Veriten.

A description of our analysis:

We are comparing recent share prices with year-end 2015. Clearly there are an infinite number of starting and stopping points one could use. We wanted to look at the long-run and starting one year after the 2014 end of the Super-Spike era seemed like a reasonable starting point.

For growth in CFPS we are using current consensus CFPS for 2024 versus the 2015-2019 average reported CFPS. We wanted to smooth the base-line to remove some of the cyclicality and other one-off effects found in a single year. With likely industry profitability in 2024 near long-term averages, it seemed to be reasonably representative of a “mid-cycle” CFPS year.

We then grouped companies into quartiles based on total shareholder returns (current vs year-end 2015).

As shown in Exhibit 3, our analysis shows a strong correlation between TSR and CFPS growth. Companies in the first quartile of TSR grew CFPS faster than those in 2Q and so on.

In looking at individual companies rather than quartiled groups, the relationship of higher TSR for higher CFPS holds. For some, there are variations to the relationship between TSR and CFPS growth that we will look to better understand.

Some broadly common themes among companies with superior EPS/CFPS growth over the 2015-2024 period:

A mix of M&A, organic growth, and stock buybacks drove the superior performance.

Of the 18 companies in the top two TSR (and CFPS) growth quartiles, 12 had declining share counts and another four had increases of less than 5%. The two that had larger increases were in fact the 2ndand 5th best performing companies on TSR amongst this universe and started the period as small-cap companies. Those two are example of excellent M&A coupled with strong organic execution having driven outperformance.

Larger companies are well represented among the top two TSR quartiles, and unsurprisingly showed absolute growth in cash flow from operations (CFFO) combined with more meaningful share count reductions.

Notably, there is less profitability (ROCE or CROCI) variation among the quartiles when looking at 2015-2019 or post 2020. In our view, the dramatic peaks and troughs seen in sector profitability is likely masking this as correlative metric to TSR. As such, it is growth in CFPS that drove TSR variation over the past decade.

Key takeaways:

Broad commodity trends, which seemingly represent 95%+ of the narrative about the outlook for the traditional energy sector, primarily impact short-term EPS/CFPS revision cycles and near-term trading sentiment.

Company specific decisions around M&A, organic CAPEX, and shareholder distributions—the combination of which impact asset quality, profitability, and balance sheet health—can drive meaningful outperformance or underperformance versus the general commodity trend.

Commodities go up and down over time, but ultimately yield only a cost-of-capital return on invested capital over the very long run (20-30-year rolling cycles). As such, unless a new super-cycle is about to emerge, which is not our call at the present, it is about finding companies that can generate growing EPS/CFPS above-and-beyond commodity price movements.

Resilience to commodity downturns is a common feature of outperformers.

M&A and organic CAPEX can be value-added, neutral, or capital destructive—there is nothing in our “G-Word” post series that implies all spending is good. Good versus bad M&A is in fact often a meaningful driver of absolute and relative share price performance.

Leaders vs Laggards: Avoid The Cycle Riders

While commodity price exposures have a significant near-term impact on traditional energy equity performance, company-specific asset/business mix, strategies, and execution drive different EPS/CFPS performance over cycles. What we will collectively call company-specific strategy execution is the difference between leaders and laggards.

We will disparagingly refer to the laggards as cycle riders: stocks that go up and down with the price cycle but inevitably lag the broader market and better performing peers over time. We have no idea why any company would want to be a cycle rider. Using numbers, cycle riders achieve the types of profitability at the peak of the cycle that we would expect leaders to achieve at mid-cycle. Clearly, there can be short-term investment opportunities in cycle riders appropriate for trader types.

The Super-Cycle Exception: Purposefully Targeting Higher-Cost Assets

An exception of sorts to the cycle rider comment would be strategies that seek to take advantage of a future commodity super-cycle. In our view, it is reasonable for companies to invest in assets that are higher on the cost curve at present but would “come-in-the-money” so to speak in a higher commodity price environment. With the important caveat that the “options premium paid” should be low, we find this to be an interesting and reasonable strategy. We do not consider this to be “cycle riding” in the event the invested capital on higher-cost assets is low and profitability during the duration of the super-cycle remains advantaged for an extended period.

Growth for Growth’s Sake Is Not The Message

We know what many of you are thinking. This is the start of the slippery slope of returning to the bad ole days of production growth targets, aggressive CAPEX expansion, ill-advised M&A that incorrectly uses “accretion” metrics as deal justification, and all related ills that long-time energy observers would never want to see repeated. The traditional energy sector had a horrid decade in the 2010s, which we promise we will never forget.

Our grounding principles on growth are as follows:

Post investment/M&A, a company should be able to generate a cost-of-capital return on capital at a normal commodity price trough and at least break-even results at a deep trough.

Notably, the first point can be true on investments geared for a super-cycle if the underlying asset/acreage/opportunity has a low upfront cost.

A company retains a fortress balance or has a clear path to return to balance sheet health even if an unexpected sharp downturn occurs within the next 12 months, which is always possible.

We would encourage companies when engaging in M&A activity to explain to investors how the transaction looks using trough-of-cycle commodity prices. Investors have understandably gone numb to headline deal accretion metrics using strip pricing, a marginally relevant metric in a vacuum, which for some reason is noted in near 100% of deal press releases. Even if for legal or other reasons that methodology needs to persist, there is no reason for managements to avoid explaining how a deal would look using trough conditions. Similarly, we would think it is reasonable to illustrate upside scenarios as well.

Company examples: Same sector, different results

We showed this example in last week’s introductory video podcast on this subject (here). It is two companies within the same energy sub-sector and therefore broadly similar macro exposures. Company B has meaningfully outperformed Company A, which correlates well with its CFPS outperformance (Exhibit 4). The reason Company B has so meaningfully outperformed Company A is due to a mix of M&A, organic CAPEX, and stock buybacks. We would point out, however, that this analysis as presented is backwards looking and says nothing about whether Company B will or will not outperform Company A going forward. We are merely trying to illustrate what has worked.

Exhibit 4: Example of two companies in same sector, where Company B has dramtically outperformed Company A

Source: FactSet, Veriten.

⚡️On A Personal Note: The Thrill of Victory and The Agony of Defeat

If you grew up in the 1970s or 1980s, you will remember ABC’s Wide World of Sports show, which started with the legendary “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat” line (must watch link) (and if you want to see the origin of the “Agony of Defeat” it is here). The equity research analyst equivalent of that are the highs and lows of making growth stock calls. I will say that the intensity of victory or defeat is more sharply felt earlier in one’s career. Career success softens you to the relatively more extreme pleasure and pain that comes from stock calls made earlier in your career.

THE THRILL OF VICTORY (growth stock calls I got right)

Tosco, refining acquisitions: I’ve talked about this one many times before. It was my first big career call: getting on board the Tom O’Malley refining acquisition growth train. I was at JP Morgan Investment Management at the time. Lessons learned: (1) a contrarian, financially-oriented management team that saw significant opportunity in a sector broadly despised at the time by both industry and Wall Street is a recipe for success; (2) the upside potential in a company with a financially-oriented, shareholder-focused management team can be significant relative to historic earnings/cash flows; (3) it's not so much about trying to guess the value of future acquisitions, as simply sticking with a management team that are proven value creators.

Anadarko Petroleum, Algeria oil discoveries: If I am remembering correctly, I was still at Petrie Parkman covering APC when the initial Algerian oil discoveries were made. It became a big holding for us at JPMIM in the mid-to-late 1990s. Lessons learned: (1) wake up, discover oil, get rich is a thing; (2) every exploration well could be a Wide World of Sports episode; (3) investors prefer the discovery and production phases more than they do the rising CAPEX after discovery but before start-up period.

Murphy Oil, Malaysia Block K discoveries: This was my first big call at Goldman Sachs. I upgraded MUR on Goldman’s 4:10 Call in January 2002 on the day my first child was born. Huge credit to my wife for enduring labor at home, as baby #1 arrived 37 minutes after we got to the hospital that evening and within 3 hours of my being on the 410 call. After 2 dry holes and the stock sinking, I remember having a conversation with one of my all-time favorite CEOs, Claiborne Deming, and commiserating with him about the dry holes. I don’t remember his exact words, but it was something to the effect that while he too was disappointed the first 2 wells were dry, they still had 1 more well to drill in Malaysia and the company remained confident in the block’s prospectivity. The Kikeh discovery well came in and the stock took off. Lessons learned: (1) I trusted and liked Mr. Deming, which helped me stick with the call through a tough performance period; (2) I didn’t panic after 2 dry holes: (3) I probably also got lucky that the third well came in!

THE AGONY OF DEFEAT (the ones I got wrong):

Oil services rally in 1990s. At JPMIM, it’s not a close call on my biggest mistake, which was completely missing the late 1990s oil services stock rally. We used a normalized (mid-cycle) investment framework, which I still very much believe in and utilize. What I missed though was the element of momentum and valuation expansion that took the oil service stocks to peak share prices well ahead of what we thought was appropriate on a mid-cycle basis. Lessons learned: (1) understanding long-term, “mid-cycle” value is a good discipline; however, on a cyclical basis, stocks can meaningfully over- and under-shoot consistent with cyclical dynamics; (2) momentum rallies (or crashes) can take stocks to extremes; you have to let it play out.

Occidental Petroleum, early 2000s turnaround. I’ve shared this story before, as it was the inspiration for my Dumb Calls I Made As A Street Analyst post (here). Oxy was a terrible stock and company in the 1990s on any metric you looked at. Long-time CEO Dr. Ray Irani remained firmly in control. I did not appreciate that the hiring of Steve Chazen would prove to be a game changer. The company purchased Altura Energy in the Permian Basin at a time everyone was bearish oil and focused on international expansion. This was of course long, long before Permian shale became THE hot area; it was completely out of favor in the late 1990s. This deal was the start of a massive turnaround in OXY shares, which was further turbo charged by the oil super-cycle that started in 2004. Lessons learned: (1) macro context matters; (2) when EVERYONE is bearish (or bullish), it is worth at least considering a different view; (3) a significant new hire can make a big difference, even when some of the old guard is still around. I have mentioned this before but only 2 out of about 30 sell-side analysts got this call right; Jay Wilson then of JP Morgan and John Mahedy of Sanford Bernstein.

Tesoro Petroleum turnaround under Greg Goff. Tesoro was an underperforming refining stock under pre-Goff leadership. I had a terrible Buy call on TSO early in my Goldman career under the prior management team. The stock was on the verge of bankruptcy in I want to say the 2002 time frame. I got lucky that the worst-case scenario did not materialize and the stock quintupled off its low-single digit low. I ended up round-tripping the stock, but it was still very much a bad call.

When Greg Goff was named CEO, I never gave him a chance. He was plucked a few layers down from the ConocoPhillips organization. I had a lazy call that Tesoro’s California assets would underperform. From start to finish, Mr. Goff drove something like a ten-bagger (a 10X increase in value) for investors. It is arguably one of the most remarkable turnaround stories in my career, especially when you consider Tesoro’s history (OXY had a much better history than TSO as an example). And I completely missed it.

I remember hosting Mr. Goff at a small investor dinner at Goldman’s annual energy conference. I don’t remember what year, but the shares by then had been performing well. He not so calmly let me have it for having never given the new Tesoro management team a chance. It was bad enough that some of the hedge funders at the dinner, not usually a touchy-feely kind of group, made an effort to defend me to him. The reality is that Mr. Goff was 100% correct: I never gave him or his new team a chance. It is one of the worst mistakes I have made in my career as an analyst. While I’ve enjoyed reconnecting with Greg in recent years, I have not until now publicly offered my regrets for the terrible job I did covering Tesoro as a Goldman analyst.

Lessons learned: (1) when new management comes in, you HAVE to get to know them; (2) if you are going to pre-judge them and stick your head in the sand, stop covering the stock or sector; (3) just because a stock starts to appreciate, it does not mean you missed it, especially when arguably one of the top refining executives of the last 30 years is now leading the company; (4) the fact that I was well-established and a successful analyst during much of Tesoro’s ascension is no excuse for doing a bad job in analyzing the shares. Career success is not an immunity potion for being lazy and not making a real effort at analysis.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Arjun - will you talk about low carbon energy M&A and how to think about it at some point please?

Given that management's ability plays such a larger role in total returns, it's quite impressive that the top quartile companies you refer to have been able to sustain continuity of good management as executive teams retire and are replaced with new people, the commodity fluctuates through the cycles, and through the changing regulatory and political landscape. It seems that a key element of top-quartile management is both their ability to navigate the business environment they find themselves in, but also their ability to train and select future top-quartile managers to eventually replace them. I've always been wary of relying on management skill too much over the long run, because even if you get a stellar manager (or team), the inevitable turnover rate means that it can only last so long, and the next group of people may not have their dedication and ability.