Underlying Oil Market Fundamentals Matter Far More Than Middle East Supply Disruptions Over The Long Run

Geopolitics

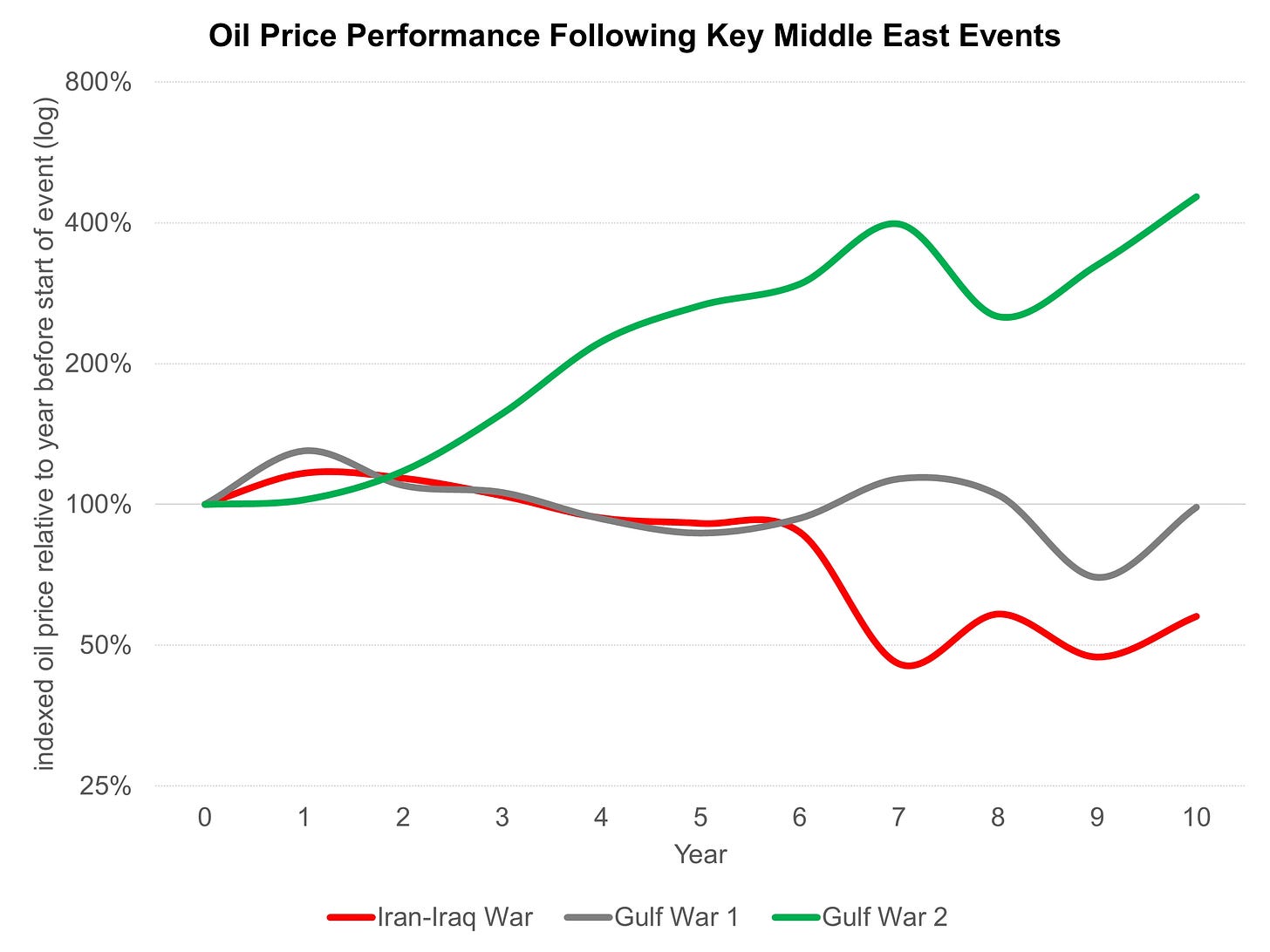

This week we look at the potential long-term impact on oil markets of Middle East turmoil. In the short-term, oil prices invariably increase to account for the risk or reality of lower oil supply from the region. In the long-run, however, we find that trends in underlying global oil demand relative to Rest of World supply is by far the key to whether the oil macro is ultimately long-term bullish, bearish, or range bound.

We examine three prior periods of Middle East turmoil and find, paradoxically, that the one with the largest, sustained disruption—i.e., the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988—turned into a structural oil bear market. Conversely, the one with the smallest disruption—Gulf War 2 in the early 2000s—was just ahead of that era’s oil super-cycle. In both cases, growth in global oil demand relative to Rest of World supply was the difference and driver of oil markets.

The current period of risk to us looks most like Gulf War 1 and the 1990s where oil was range-bound. Today that range is $50-$90/bbl for WTI (West Texas Intermediate) rather than the $15-$25/bbl (nominal) seen previously, and we would describe skew as perhaps slightly to the upside given maturing Tier 1 US shale oil supply (i.e., can yield competitive returns on capital below $70/bbl WTI) and a dearth of major new oil projects being contemplated post 2026. Slowing oil demand growth in China and generally lackluster global GDP growth are the main factors that keep us from calling for a structural bull market.

There is no one-size-fits-all corporate strategy advice to give, but as a general rule during higher priced periods we would prefer some combination of debt paydown, cash build-up, dividends over stock buybacks, and caution towards making acquisitions, with the opposite the case during lower priced periods. For investors, as always, the goal is to find the companies that can generate mid-teens, full-cycle returns on capital (CROCI and ROCE) and superior per share growth versus both the broad energy sector and S&P 500.

1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War: BEARISH

Arguably the best example of Middle East turmoil leading to a long-term disruption in oil supply, but where the impact on oil prices, oil equities, and corporate strategy was very different than (likely) consensus expectations at the time was the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988. We say “likely” impact on consensus because this was pre-career for us (middle and high school student). A few points:

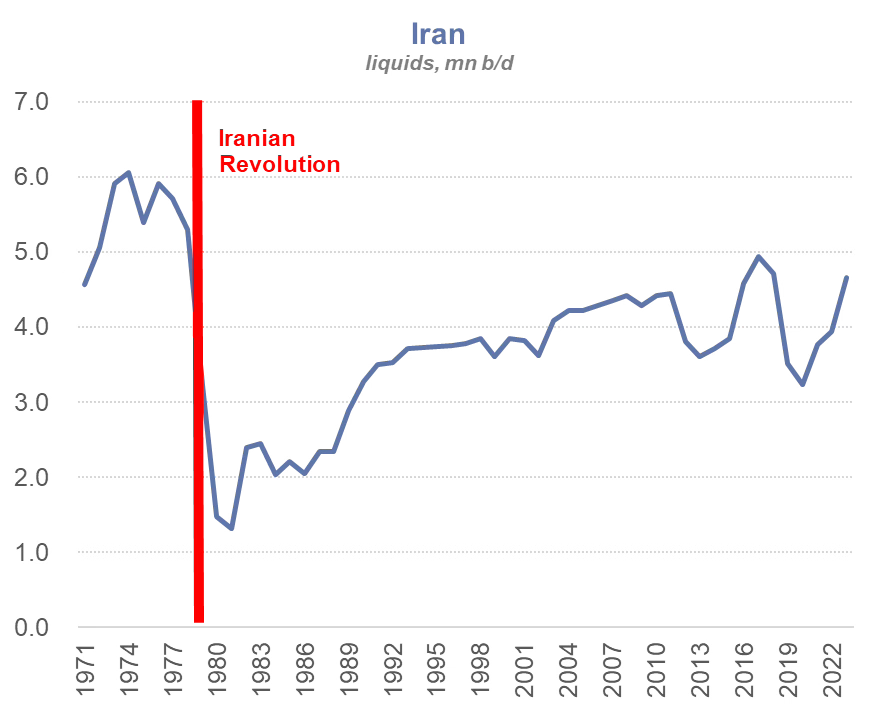

Relative to a 1979 pre-war baseline, combined production from Iran and Iraq fell by 4.5 million b/d by 1981, or a whopping 7% of 1979 global oil demand.

If we instead use peak production from Iran and Iraq during the 1970s, production in 1981 was 7.4 million b/d lower, or 11% of 1979 oil demand.

Iran has never come close to returning to peak production levels seen in the 1970s of around 6 million b/d—this was a major permanent hit to its oil supply.

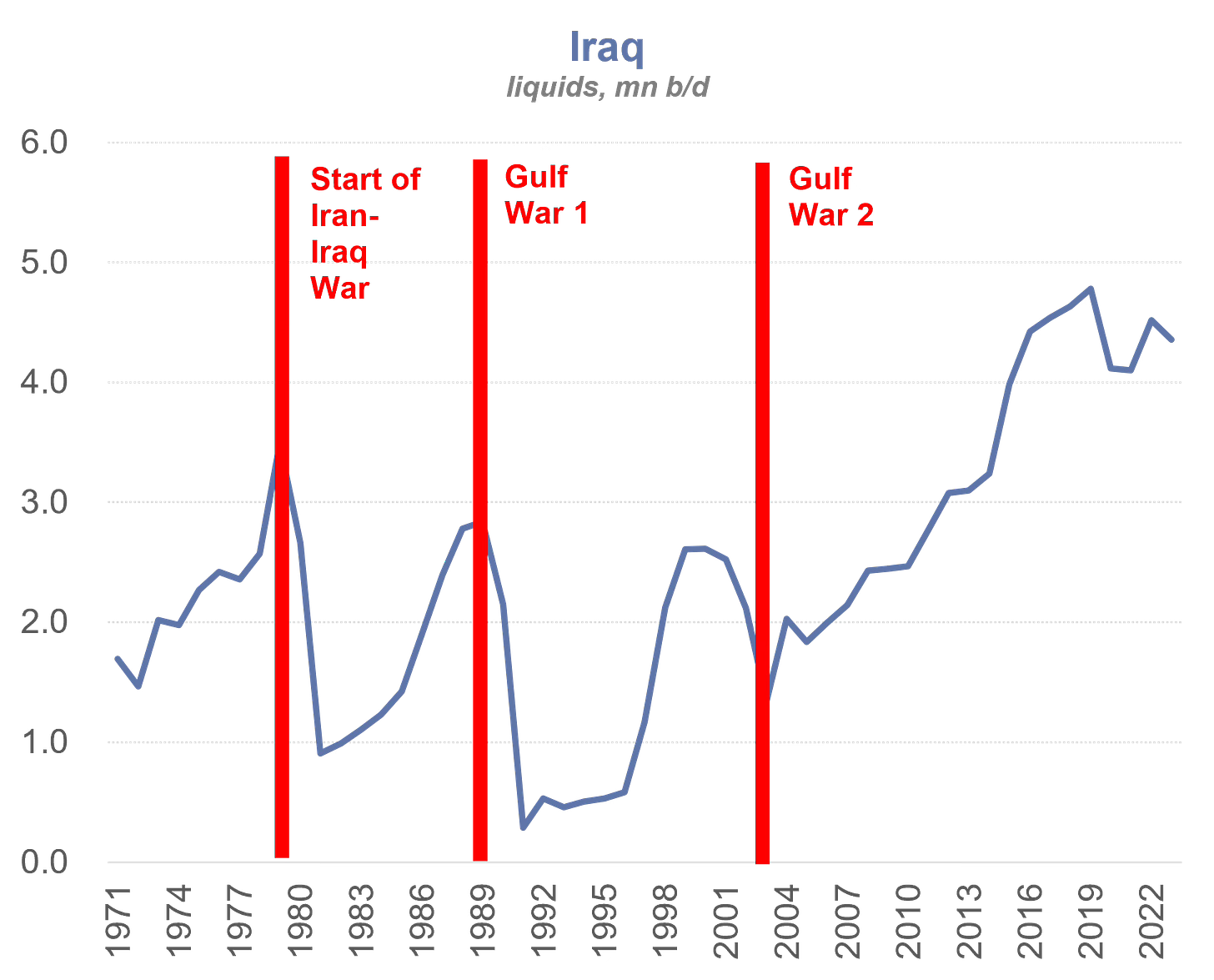

For Iraq, it didn’t exceed its 1979 high until 2015, some 36 years later!

There is no better example of a long-term supply disruption that we are aware of than the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988.

Exhibit 1: Iran liquids production

Source: Energy Institute.

Exhibit 2: Iraq liquids production

Source: Energy Institute.

Yet, we think most Super-Spiked readers will know that 1979 was the peak for the energy sector and oil prices crashed in 1986, which was the first time Saudi Arabia and its fellow OPEC producers grew tired of subsidizing booming non-OPEC supply. Oil prices were not as freely traded on NYMEX or other commodity markets like we see today, but that likely only delayed the day or reckoning.

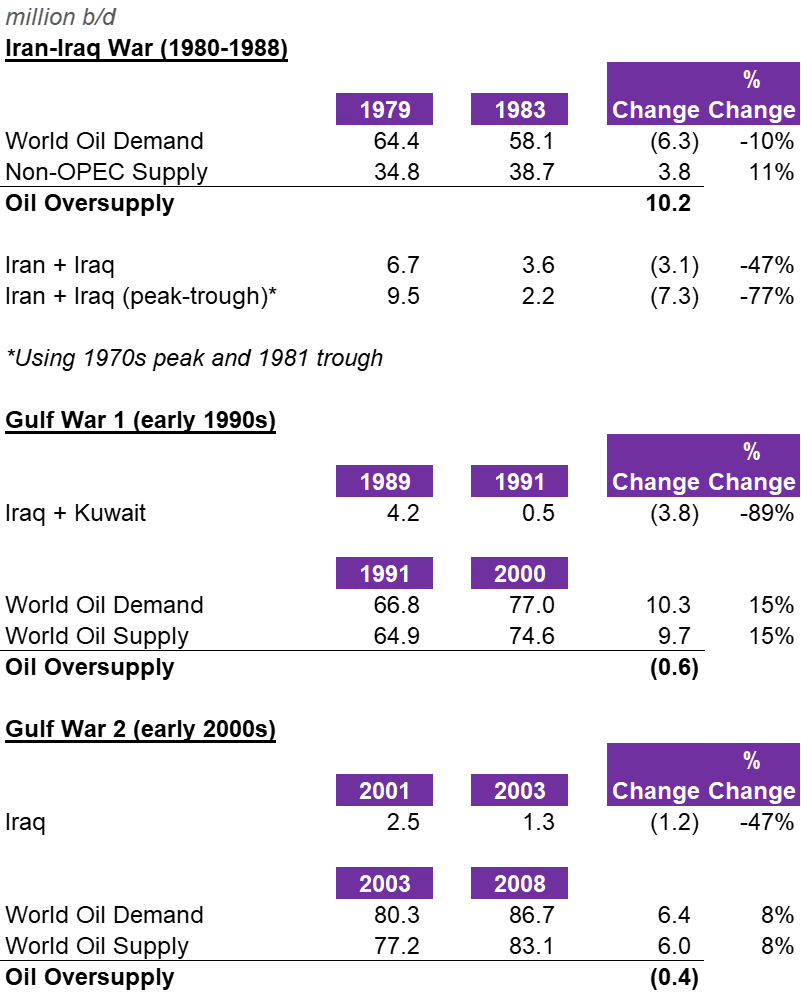

So why didn’t a major, long-lasting Middle East supply disruption not prove long-term bullish for oil prices or equities? It is because global oil demand declined by 5.4 million b/d, or 8%, between 1979 and 1984, as major OECD economies substituted fuel oil out of power generation in lieu of coal and nuclear. At the same time, non-OPEC supply was booming, growing by 5.3 million b/d, or 15%, between 1979 and 1984.

Exhibit 3: Supply/demand impact from key events

Source: Energy Institute.

Exhibit 4: Oil price performance following key Middle East events

Source: Energy Institute.

1990s: Gulf War 1: NEUTRAL

Gulf War 1 saw combined Iraq + Kuwait oil production fall by a combined 3.8 million b/d in 1991 versus the 1989 pre-invasion high. This was the first major oil supply disruption since the 1970s-early 1980s super-cycle. By this time, oil was actively traded on NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange) and other exchanges and a meaningful oil price spike occurred. However, despite only a partial resumption of oil supply by 1993 and a full recovery not occurring until 1998, oil prices were generally range-bound in the 1990s, as rest of world oil supply was able to keep pace with growing oil demand without requiring a major (and higher cost) new expansion phase. In essence, oil supply was still able to easily grow from low-cost “exploitation/debottlenecking” projects following the 1970s CAPEX boom.

The period ended with investors and corporates convinced that oil prices would stay low “forever” and that a major consolidation wave to cut costs and improve efficiency was the only way to survive and thrive (i.e., the “Super Major” M&A wave of 1999-2002). That turned out ultimately be too bearish of a viewpoint. However, for the decade that followed Gulf War 1, range-bound oil was what transpired.

2000s: Gulf War 2: BULLISH

Somewhat ironically, Gulf War 2 saw the smallest supply disruption of the three events we are highlighting yet this was the one that ultimately transitioned to an oil price super-cycle and our career-making “Super-Spike” call at Goldman Sachs in March 2005. While we would not characterize Iraqi supply as being meaningfully disrupted from Gulf War 2 relative to the trends seen since Gulf War 1, Iraqi oil supply growth in the 2000s did meaningfully underperform the rapid growth expectations many market participants assumed following the initial wave of hostilities.

Disappointing Iraqi oil supply growth was a theme consistent with broader global oil supply challenges, where the “easy” oil growth of the 1980s and 1990s gave way to the need for new major projects and exploration. At the same time, the BRICs economic boom, in particular for China, drove especially strong global GDP and hence oil demand growth that was reasonably price inelastic. We believe most Super-Spiked readers are well aware of this history given its recency.

2025+: Israel-Iran: Neutral with a slight positive skew

We believe the current macro backdrop is closer to the 1990s example than the other two. We are clearly not just ending a super-cycle—the last one ended over 10 years ago—meaning the risks of a structural demand decline AND a surge in non-OPEC supply we do not see as likely. We also so do not seem to be on the verge of a BRICs-like global GDP surge, though we would love to be proven wrong on this one. At this time, an oil demand expansion of around 0.75-1 million b/d per year is a reasonable base-case for the remainder of the 2020s. We believe something closer to 1.3-1.5 (or higher) million b/d per annum would likely be needed to drive a stronger oil price upcycle.

Hence, our core call has been “Super Vol” (volatility) rather than super-cycle. The risk of a disruption in Iranian oil supply—and potentially some of its neighbors—is an obvious upside risk. But the potential for weaker GDP and oil demand growth a corresponding downside risk. We also suspect that if oil were to trade in say an $80-$90/bbl range for a period of time, higher cost of supply US shale oil would find its way to market. Both of these points would have to be proven to not be true for an Iran-related disruption to translate to a new structural bull market.

Q&A on Middle East turmoil

How is a supply disruption not always bullish?

It is bullish short-term. It clearly hasn’t always been bullish long-term. At the start of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 after oil prices were up 10-fold and oil equities had experienced a generational bull market, the right call was to sell the sector. From a corporate strategy standpoint it would have been to sell the company or sell assets into a bullish environment and get ahead of what ultimately became a structural bear market. Supply disruptions don’t exist in a vacuum. Demand and rest of world supply adjusts accordingly. Capitalism and the market works.

Isn’t the fact that many oil commentators are not pound-the-table bullish a sign that everyone is being too complacent about this event?

Maybe. But to be long-term bullish, a more positive view of demand and clearer evidence of rest of world supply disappointments are needed. That said, there has been considerable concern, which we have shared, about weaker oil supply/demand balances in 2H2025 and 1H2026. It is possible that a disruption in Iranian (or neighbor) oil exports could eliminate that downside risk to oil. At Super-Spiked, we have refrained from partaking in the short-term oil price guessing game. However, in the context of a post about supply disruptions, it seemed appropriate to comment in this instance.

What if the Straight of Hormuz is closed? Isn’t that an uber bullish upside risk?

Yes, in the short term. But for how long could it conceivably be kept closed? There is nothing about the conflict-to-date that suggests Iran has a robust military. At this moment, our guess is that it would mark the oil price peak. My former colleague Jeff Currie had a long-running exhibit he used that had the tagline “Nimitz in A.G.” referring to the USS Nimitz being stationed to protect Middle East oil flows in the Arabian Gulf. On cue, this ship is still around and apparently heading to the Gulf per recent news reports (here).

So oil equities are likely to trade sideways if oil is going to be range bound?

We believe companies that can generate mid-teens, full-cycle returns on capital (CROCI and ROCE) and superior per share growth versus both the broad energy sector and S&P 500 will perform well. A super-cycle is not a prerequisite. It remains our view that we are in year five of a period of structurally better profitability after a tough stretch from 2008-2020. We expect energy’s weighting in the S&P 500 to eventually return to the 8%-12% range it has historically experienced (versus low-to-mid single digit currently), albeit the mix of companies is likely to be more diverse and across different energy sub-sectors versus historically being dominated by the integrated oils.

⚡️On A Personal Note: Can’t Deny Doug Terreson Made Some Great Calls During His Career

I just finished reading a really fun book written by a long-time colleague, competitor, and friend Doug Terreson. It is a memoir of his career as a Wall Street energy equity research analyst titled Can’t Deny It (here) I first met Doug in the early 1990s at the very start of my career when I was a newly minted junior equity analyst at Petrie Parkman and he was a client at Putnam, a major Boston investment firm (Doug is a few years my senior). I actually remember how pleasant our first interaction was at an analyst meeting. As a very junior sell-side analyst, it was exciting for me to speak with the Putnam oil guy and Doug, true to form, made me feel at ease.

Shortly thereafter, Doug went to Morgan Stanley (via Paine Weber) and I became a top client of his as a buy-sider at J.P. Morgan Investment Management. I did a number of notable international trips that Doug hosted, including my first ever visit to China (Beijing) in the 1997-ish time frame. Upon arrival in Asia, we flew on a Morgan Stanley private jet to various cities across southeast Asia, something I am sure has long been discontinued as a practice for sell-side analysts traveling with buy-side clients. On our trip, there was a young Chinese man that kept to himself in the back of the plane and quietly took notes in our meetings. I finally asked Doug toward the end of the tour who it was. An interpreter? Definitely not a body guard. A Morgan Stanley junior analyst in Asia? None of the above. It was China premier Jiang Zemin’s son! Now that I think of it, this likely explains the availability of the private jet. (Note: I believe I am recalling all of this reasonably correctly…it’s certainly based on true story.)

I remember Doug’s “Super Major” M&A call in the late 1990s like it was yesterday. I was still on the buy-side then and it was a big deal. A competitor of his had also made an M&A call around that time titled “No More Mr. Nice Guy.” That other analyst was the person I regularly voted #1 on various surveys (Doug was typically Top 3 for me). But in this case, I did observe the “Super” added something to Doug’s call that stood out from the others. When my Goldman team and I made our “Super-Spike” call in March 2005, our use of the word “Super” was from the direct observation of how much it helped Doug from a marketing standpoint. I owe Doug an inspirational assist on that one—something I don’t believe I’ve ever told him.

Doug and I were friendly competitors during my 15 years at Goldman, after which I again became a client of sorts to him when I joined Warburg Pincus as a senior advisor. During our time competing, I do think investor clients valued the macro calls that Jeff Currie and I made. I don’t remember Morgan Stanley, for example, being part of the 2005-2008 oil price debate that Doug retells in the book. I remember Ed Morse of Citigroup battling Jeff Currie (both were commodity analysts and didn’t cover equities). For me, I recall the Berstein team of Ben Dell and Neil McMahon being prominent antagonists to us far more than I remember Doug’s oil calls from that period. I will say that when I joined Warburg and started receiving his oil macro work again, I did find it useful and interesting.

We both had bullish refining calls in the 2000s. There is zero doubt that Doug’s “Golden Age of Refining” branded his work much better than did I. I was still in “Super-Spike” mode most likely. “The Pledge” came during my post-Goldman advisor/board years (Doug had also since moved on to Evercore ISI) and there is zero daylight on Doug’s emphasis on full-cycle profitability and my own. I believe Doug deserves significant credit for pushing industry to being more financially focused, a point that is also featured prominently in Super-Spiked and in the work we do at Veriten.

When my retirement from Goldman was announced in February 2014, Doug was among the first to reach out to me, congratulating me on my career and offering advice from the early retirement he (briefly) took at Morgan Stanley. We were technically competitors at the time and I appreciated the conversation. His advice was good (paraphrasing): “Congratulations Arjun on a great career. You will have a lot of very different opportunities come your way, just as I did. Don’t jump at the first one. Take time to wind down from your career and figure out what makes most sense for you.” Absolutely great advice that was also given by a number of fellow Goldman retirees.

I have had more than a few people ping me saying they enjoyed Doug’s book, but found his style to at times be too self-congratulatory. In all of our 1:1 interactions, I have always found Doug to be very friendly, polite, and professional—a southern gentleman. I conclude that the tone that in a few places in the book is off putting to some is reflective of the confidence that is required to be a leading analyst. It is who he is and contributed to the significant career success he achieved.

As an energy team leader and Director of Research, I always implored Goldman analysts that there is no point in making undifferentiated, within consensus kind of calls. What are the big calls that stand apart from the rest of the Street? If I want a consensus view, I can pull up Bloomberg or FactSet—Goldman certainly didn’t need to pay analysts an above-average income to spit out consensus mediocrity. If a 1 standard deviation move in oil prices is $15-$20/bbl—and 1.0-1.5 standard deviation moves regularly happen—there is no point to forecasting crude oil within $5/bbl of where everyone else is as an example. Make a call. Bullish or bearish. Be bold. Stand apart. Where is the world headed?

Doug exhibited all of these characteristics. Whereas I am best known for my Super-Spike call, Doug can claim 3 branded calls to his name! If you want a first-hand account of the energy sector over the past 30 years from a financial markets perspective, I highly recommend Can’t Deny It. I also recommend it for anyone that wants to understand what it takes to be a leading Wall Street equity research analyst.

Congratulations Doug on a great career and a great read! Some advice back to you: start a Substack where you do not charge for content. Nothing is more important than getting energy right, and there are a lot of “wrong” views out there. Management teams, investors, policy makers, and other energy leaders would benefit from continuing to hear your thoughts. And if you are in my neighborhood, let’s get out for a round.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Well,we didn't need to wait long to test the 'super vol' proposition...The Nimitz was there,the Straights of Hormuz are still there,and all of us will be tuned in to the 10 o'clock Presidential address.I would venture the guess that the event will be framed as a 'necessary intervention' and not a 'regime change' rather than an act of war, which seems to require Congressional approval-comically incongruous as the notion of Congress approving anything may appear.

You travelled on a private jet with Jiang Zemin's son? So many stories. When is your book coming out?? You have to get these stories down all in one place. A family member wrote his autobiography and when I read it I realized that though I had known him for so many years there was so much I did not know about him. Now I encourage everyone to get their stories written down.