Volatility Not Vienna Redux: Ignore OPEC Noise Most of the Time

Navigating the Energy Crisis Era

Volatility, not Vienna was the title of a 2000 era report we wrote at Goldman Sachs (Exhibit 1). The basic premise still holds 23 years later:

OPEC is way over-analyzed by just about everyone.

OPEC does not “control” oil prices, though it can have a noticeable impact at times. Rather, OPEC countries are important oil producers with an outsized geopolitical relevance.

OPEC cuts “work” best at the trough of the cycle when inventories are high, oil prices are low, producers are losing money (or break even for the better ones), and the economic outlook is about to inflect favorably (usually hard to see in real time).

OPEC’s inability (some say unwillingness) to raise production at or near price peaks we argue is more telling about the limits of their spare capacity than a purposeful goal of extracting greater revenues.

OPEC has a natural incentive to overstate production capacity in order to exert geopolitical influence. We are surprised at how many observers take OPEC country declarations of production capacity at face value.

Over the past twenty years, Saudi’s demonstrated production capacity has arguably only increased by 1 million b/d from around 9.5 million b/d in the early 2000s to 10.5 million b/d today (Exhibit 2). By “demonstrated production capacity” we mean a country has to have shown it can actually produce at a certain level over several months. Doing a similar analysis for other countries reveals that core OPEC spare capacity is still quite limited (Exhibit 3).

At a middle of the road oil price (like now), we do not see the relevance of the Saudi cut announced on June 4.

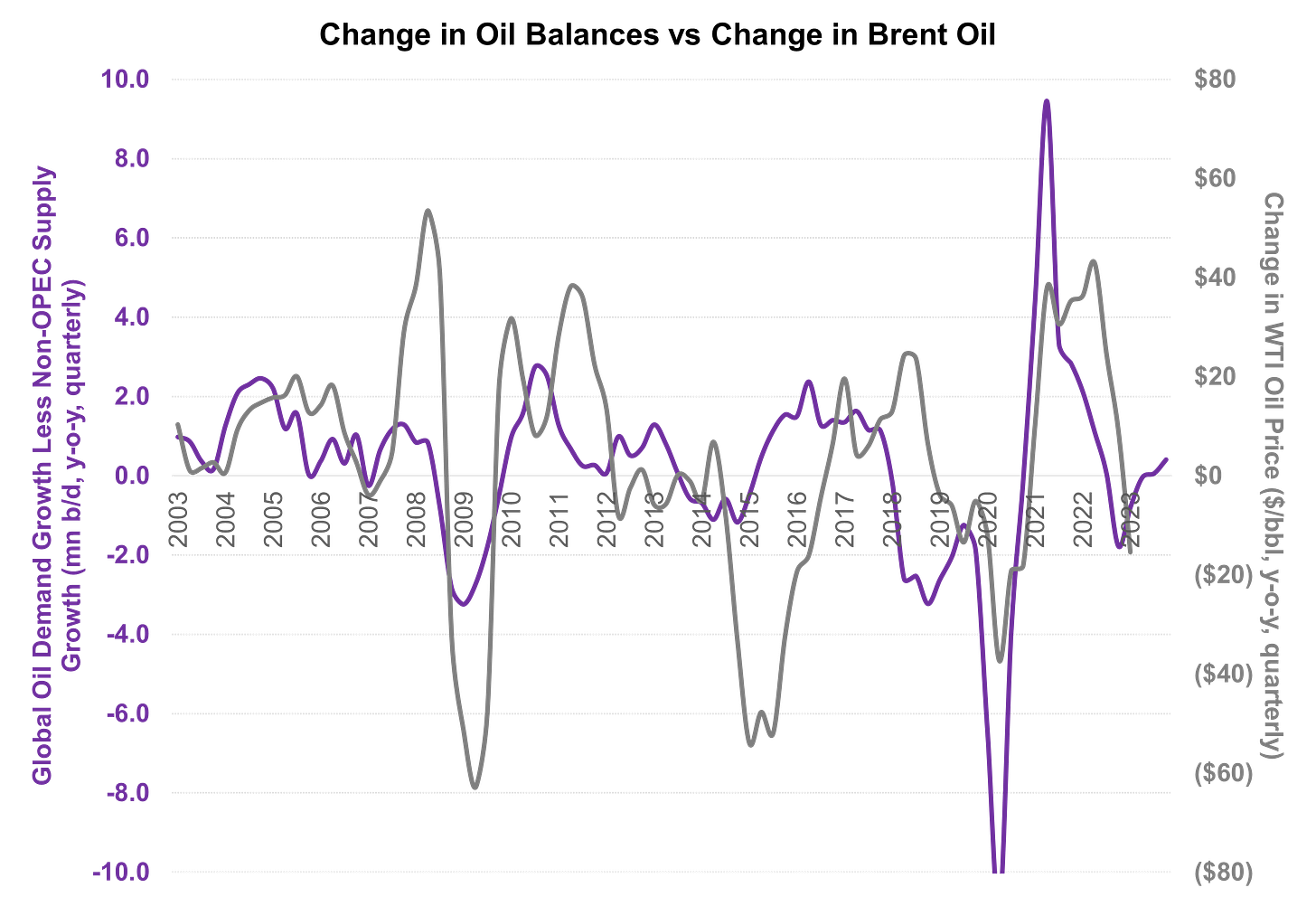

We have just gone through a three-quarter period where non-OPEC supply growth has exceeded global oil demand growth—usually a time of softer oil prices (Exhibit 4). If oil demand growth does re-accelerate in 2H 2023 as many of the leading oil market observers predict and if non-OPEC supply growth moderates as expected, it is possible that oil markets rally. But this is what needs to happen. We do not believe Saudi or OPEC can cut their way back to a bull market.

The fact that a large portion of the world's oil supply is concentrated in a handful of producers supports:

ensuring the United States and Canada maintain a healthy and growing oil and gas sector;

growth in domestic oil supply for developing countries to the extent it is geologically possible; and

oil demand efficiency improvements and growth in electric vehicle sales, especially in oil importing (or future oil importing) countries.

No oil company should or will change CAPEX or M&A plans based on OPEC noise. It’s not even obvious to us that OPEC has raised the price floor; in a global recession scenario, oil prices could have meaningful downside risk. Rather it would be cost inflation and shale maturing that might be raising the floor price for oil.

Exhibit 1: Volatility, not Vienna theme holding strong 23 years later...and proud to have worked with the super star team in the left column

Source: Goldman Sachs.

Oil Macro-in-Pictures

Exhibit 2: Saudi crude oil production capacity has arguably grown by a mere 1 million b/d over the past 20 years from around 9.5 mn b/d in the 2000s to 10.5 mn b/d currently using our preferred metric of demonstrated production capacity

Source: IEA, JODIData, Super-Spiked.

Exhibit 3: “Core-5” OPEC spare capacity we see as limited, in particular if Iran is excluded

Source: IEA, Super-Spiked.

Exhibit 4: Global oil demand growth versus non-OPEC supply growth correlates with changes in Brent oil prices; the past three quarters have coincided with a period where growth in non-OPEC supply exceeded global oil demand; the debate now is when will it favorably inflect? In 2H2023 as most expect or in future quarters if global economic weakness persists?

Source: Bloomberg, IEA, Super-Spiked.

OPEC+ and "Energy Transition"

Disclaimer: We understand and mostly agree with the various critiques of the term "energy transition." However, it is the commonly used phase that everyone understands. As such, we too will continue to use it for the foreseeable future. Our use of the term does not imply we agree we are actually in a literal transition. Rather, we believe the world is diversifying its sources and uses of energy demand, which is needed in order to help the other seven billion people that do not live in the United States, Western Europe, Canada, or Japan gain greater access to improved living standards.

There is perhaps no greater advertisement for the need for a healthy and growing US and Canadian oil and gas sector than the existence of OPEC (and now OPEC+) meetings. We are all fortunate that despite overt hostility from many leading politicians, academics, activists, and journalists, the traditional energy sector in North America has regained its footing after a bad last decade (the 2010s). A healthy energy evolution includes a strong and growing North America oil and gas sector.

Should traditional North American energy companies be bigger players in new, lower-carbon energy sourcing? In our view, the answer is “no” for most, though we are not opposed to companies pursuing logical business extensions (e.g., renewable fuels for refiners, CCUS for certain upstream companies) or having venture capital exposure to new energy sources.

Why do some US and Canadian politicians, policy makers, and activists want to weaken the standing of their own oil and gas companies in a world that continues to include OPEC+? We have no idea.

The existence of OPEC+ makes the case for developing countries to pursue all forms of energy supply source diversification. Let's use China as an example, a country that currently imports on the order of 12 million b/d of oil. The rapid rise of EV sales in China makes perfect sense as a means to try to limit, and perhaps someday reverse, growth in oil imports. For a country that is likely to remain by far the world's dominant user of domestic coal, we would surmise that the main reason China is looking to grow EV sales is to reduce dependence on OPEC+, in contrast to oft-touted climate objectives. From China's perspective, we would think that domestic coal-fired EVs are preferable to OPEC+-fired ICE vehicles.

OPEC+ and Corporate Strategy

We would not expect OPEC+ actions or inactions to impact corporate strategy, CAPEX, or M&A decisions being considered by North American oil and gas companies. We do not believe Saudi's willingness to unilaterally reduce supply raises the potential floor crude oil price, especially in a global recession scenario. It is our view that OPEC spare capacity overall remains limited and that higher capital spending will be required in order to meet future demand growth.

OPEC+ and Investors

By now, the commentary for investors will not be surprising: Most of the time you can ignore OPEC+ noise. The points on OPEC+ that we think are most relevant are:

Having a view on spare capacity that is distinct from what countries claim; we believe spare capacity remains limited using our preferred demonstrated production capacity metric.

Recognizing that there is a big incentive for oil importing countries to want to diversify away from oil demand, if possible.

Recognizing that diversifying demand is not easy and the math on seven billion people using 3 barrels of oil per capita versus the lucky 1 billion using 14 barrels per capita is overwhelming and we believe more than offsets the demand diversification impulse.

For publicly-traded energy equities, understanding that the sector's ROCE cycle (and mini-cycles) is more important than obsessing about OPEC+.

OPEC+ actions at the trough of the long-term oil cycle is where the greatest opportunity exists to accelerate the inflection from bear to bull market. It's possible we are near the low point in a mini-cycle, but we are not near a major trough like we saw in 2020 or 2009.

The now nearly four quarter downdraft in oil prices, we believe, will end when global oil demand growth again exceeds non-OPEC supply growth. Our base-case models that to occur in 2H2023 with risk skewed to it being delayed due to economic weakness.

OPEC+ and Short Sellers

Having senior OPEC+ officials blame bearish speculators for the decline in oil prices is about as meaningful and accurate as when CEOs do it for their share prices. In other words, it's typically completely mis-placed and in our view mainly reflects a misunderstanding of how markets work. If your stock (or main export commodity) is under pressure, it's not personal. It reflects bearish expectations on future fundamentals. Those expectations may be accurate or ultimately inaccurate. But whining about short sellers causing a price decline is super lame.

⚡️On a Personal Note: Joining an All-Star Team

I joined Goldman Sachs in July 1999 and launched coverage of the U.S. integrated oils sector that December. When I look back at the analysts listed on the cover of the July 13, 2000 report, I realize I had forgotten how lucky I was to have joined a veritable all-star team of energy research colleagues, just about all of whom went on to achieve tremendous career success either at Goldman Sachs or elsewhere.

At the time of this particular report, no one listed on the cover was a Goldman partner; I believe two may have been managing directors. But I knew I was fortunate to be joining the firm. I was a fan of Steve Strongin and his then emerging commodities research franchise and was a proponent of Anthony Ling and team’s “Stupid Oil Price” report series from their Schroeders days.

Of the twelve analysts listed, five were eventually named a partner of Goldman Sachs, of which one became our Global Director of Research (DOR), three became regional DORs, and the fifth Head of Commodities Research. One person went on to a successful buy-side career at Capital Research. Another became a partner at Apollo and now runs his own private equity firm. Greg Pardy is still a leading Canadian oils equity analyst at RBC. Jeff Currie of course remains the Street’s pre-eminent commodities guru. Only Jeff and Allison still remain at Goldman, with Allison having moved on to start the successful Top of Mind report and podcast series.

The debates we had as a team about the outlook for oil prices and the energy sector were intense and engaging. It certainly made me a better analyst. You debate ideas fiercely until The Call can be made. Given inherent commodity and market volatility, the idea was almost always to figure out where consensus was most wrong and to go in the other direction, hard. Which two standard deviation move is about to happen? You do your best to stick together as a global team, but can emphasize different aspects of the view pertinent to your region.

When I look back on my career stops at Petrie Parkman, JP Morgan Investment Management, Goldman Sachs, and now Veriten—and then add in the advisor/board roles at ConocoPhillips, Warburg Pincus, Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy, and ClearPath—it is pretty ming boggling to think of the collection of super star analysts, executives, portfolio managers, investment bankers, capital markets professionals, policy makers, and academics I have had the opportunity to work or interact with. A big thank you is insufficient but will have to suffice to each and every one of them.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Thanks a million Arjun. I really appreciate your Saturday update.

Better phrase is “energy addition “ rather than energy transition.