What does pariah state status imply for future Russia oil exports?

Spoiler alert: Pariah states are not reliable oil suppliers

This week’s post builds upon the concept of “good” versus “bad” barrels I introduced in last week’s note and examines the reliability, or lack thereof, of oil supply from pariah states. The topic has taken on greater urgency as there are growing signs that Russia is headed toward pariah state status. To be clear, this post is not about whether there will short-term disruptions in Russia oil supply due to sanctions (growing in possibility) or war-related disruptions (seems much less likely). Rather I am asking about the degree to which there is potentially meaningful long-term downside risks to Russian oil supply as a result of its invasion of Ukraine as it turns into a full blown pariah state.

While pre-Ukraine, Russia was generally not found on most people’s Top 10 list of “nicest countries in the world,” any negative views were usually (and appropriately) focused on its leaders like president Vladimir Putin rather than the country itself or its people more broadly (I know how much I enjoy all of my interactions with former clients, colleagues, and friends of Russian heritage). While that generally remains the case today, there are mounting USA/EU sanctions and a bigger trend of “self sanctions” as private companies especially in the west but also around the world jump ship or otherwise refuse to do business with anyone or anything associated with the country; I am referring to all economic sectors here, not just energy, which actually remains mostly unsanctioned. It would be hard to believe that Russia’s oil industry would be insulated from the negative effects of having to go solo in the world.

As part of the energy transition era, it is my view that the USA, Canada, and Europe, along with their allies, should look to eliminate dependence on pariah states, which historically have been unreliable oil suppliers by virtue of their pariah state status. While it is true that crude oil is a global business and geopolitical volatility would still have an impact on energy prices faced by all countries, eliminating the risk of a physical shortage of oil and enhancing the willingness to isolate bad actors should still be key objectives. A healthy energy transition era is one that seeks to eliminate dependence on pariah states—an achievable long-term goal in my view.

As a Top 3 producer of crude oil and natural gas and an important producer of a number of agricultural and industrial commodities, the risk of Russia turning into a pariah state that negatively impacts its long-term export potential could have a meaningful negative impact on the economic health of the rest of the world. In this post I will look at examples of current or past pariah states including Iran, Venezuela, Libya, and Iraq. I also look at the collapse of the former Soviet Union (FSU). When Iraq turns out to be the former pariah state “winner” of this group, the seriousness of the risk of long-term downside to energy exports from Russia should not be taken lightly or under-estimated.

I don’t see how there could be any debate that energy availability, affordability, reliability, and security would be enhanced with greater amounts of “good” barrels from the United States and Canada and fewer “bad” barrels from Russia and Iran. As importantly, I don’t see how its even a close call that the opportunity for enforcement of appropriately strict climate and environmental regulations is significantly higher in the United States and Canada than Russia or Iran. There couldn’t possibly be a single person that would rationally argue Russia and Iran are better climate/environment stewards than the USA and Canada.

Is Russia turning into a full blown pariah state?

I introduced this topic in a short Macro Commentary video (here) last week and will now flush out some details. With civilian casualties and atrocities mounting as president Putin's invasion of Ukraine continues with no end in sight, what would Russia becoming the newest pariah state mean for its long-term oil supply? Policy makers and energy market participants have been focused on the risk of short-term Russian supply disruption due to sanctions, which are reportedly occurring but primarily due to "self sanctioning" that has an uncertain duration (i.e., traditional buyers are hesitant to purchase Russian oil at this time for a variety of reasons). Relative to a month ago, the risk is no longer trivial that Russian oil could face long-term structural downside risks.

There are some important differences between Russia and other pariah states in that it is not simply an oil petrostate (partial list below).

Russia is one the world's largest natural gas producers and a leading supplier to the European Union.

Russia is an important player in many agricultural and other industrial commodity markets.

Russia represents the core of the old Soviet Union and a nuclear super power that has long rivaled the United States.

Russia also has seemingly friendly (or at least non-adversarial) relations with two of the most important future energy demand centers, China and India, which, at this moment, seemed poised to absorb increased Russia oil flows that may no longer be heading west.

All of these points suggests that even if significant US and European sanctions were to persist—as seems likely at this moment—Russia may not be doomed to follow the same path of perpetual decline as seen in places like Iran and Venezuela.

With that said, the track record of countries facing near universal condemnation without a clear avenue to tap mainstream capital markets or access to commodity export revenues tend to have unhealthy oil companies and industry dynamics. To be sure, Russia is not yet facing material energy export sanctions. But worldwide revulsion about the images emerging from Ukraine in the wake of the Russian military's offensive appear to be beyond the point of no return.

One of the bigger questions is the ability of Russia's notionally "independent" major oil companies, including Rosneft and Lukoil, to continue to invest capital to maintain let alone modestly grow oil production. In the event, Russia does become the latest sanctioned country on a variety of fronts including energy, the experience of other sanctioned countries suggest that crude oil supply is likely to enter into long-term decline as any remaining energy revenues are diverted to prop up the state, with inadequate CAPEX sanctioned to support (let alone grow) oil production. Somewhat ironically (speaking as someone from the Wall Street/investor world), sharp increases in dividend payments would likely be a red flag of the state seeking to extract near-term cash flows from its producers, risking inadequate maintenance/growth CAPEX.

To be sure, there are plenty of resource opportunities in the rest of the world that could be developed that could fully replace Russian oil exports. But in an environment where the western oil industry was already under massive investor pressure to both improve long-term ROCE while also being cognizant of long-term downside risks to oil demand under various energy transition scenarios, the timing mismatch of new supplies being developed to replace potentially declining Russian oil supply seems high.

My pre-Ukraine oil supply/demand model had contemplated structural Russia oil supply growth of around 1% per annum to 2030. Over a decade this would total a cumulative 1 mn b/d of supply. The risk is not that it is flat or down 1% per annum. The question is could Russian exports follow an Iran or Venezuela-like path of down 25%, 50%, or even 75%? Based on a month of an already devastating war in Ukraine, the odds are growing that Russia will be excluded from the normal functioning world we all live in.

Pariah state peer group analysis

Iran: Pariah state since 1979 (43 years and counting)

Iran was producing 5-6 million b/d of oil (all figures are liquids, which is crude oil + natural gas liquids) in the 1970s prior to the Iranian Revolution. Since then, liquids output has been stuck between 3.5-4.5 mn b/d. Currently, there is no visible path to Iran ever returning to its pre-revolution highs. It has been over 40 years since the Iranian Revolution.

Venezuela: Pariah state since 2000 (22 years and counting)

In the 1990s, Venezuela enjoyed a dynamic and rapidly growing oil industry where western oil companies teamed up with PDVSA, the national oil company, to develop what is unquestionably the world's greatest "oil sands" resource (unlike Canada's oil sands region, Venezuela's requires far less energy for commercial production; heavy oil upgrading is still required). The ascension of Hugo Chávez to power changed everything for the worse—a current example of why I am pro-capitalism, anti-socialism. From a high of 3.2 mn b/d, Venezuela currenlty produces just 0.5-0.7 mn b/d. It has been over 20 years since president Chávez dramatically changed the direction of Venezuela.

The recently reported outreach by the Biden Administration to Venezuela to produce more oil is laughable. Venezuela currently produces in total about what the US shale oil industry can add on an annual basis for the remainder of this decade.

I would note that Venezuela is a country that has attracted talk of Chinese oil company involvement, substituting the yuan for the US dollar, and related noise. All I would say is that there is nothing about Venezuela’s oil production path over the past 20 years that would provide optimism that China can prop up the oil sector of a pariah state.

Libya: Failed state since 2011 (11 years and counting)

With the 2011 demise of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya has probably technically transitioned from pariah to failed state status. Regardless, versus production levels that were regularly betwen 1.5-1.7 mn b/d, recent production has not typically exceeded 1.1 mn b/d with long stretches well below that level. It is just over a decade since Colonel Gaddafi was deposed.

Iraq: Best performing former pariah/failed state (10 years after pariah state removal to return to prior highs reached 44 years earlier)

Incredibly and to my surprise, Iraq is actually the best performing current or former pariah/failed state, with recent production at an all-time high. To be sure, post Gulf War 2 and the demise of Saddam Hussein, many analysts had predicted Iraq would reach 7-10 mn b/d by 2010. In 2019, production reached an all-time high of around 4.7 mn b/d, well short of the excessive optimism expressed by many post-Gulf War 2 (yours truly never agreed with those uber-optimistic forecasts for Iraqi oil supply).

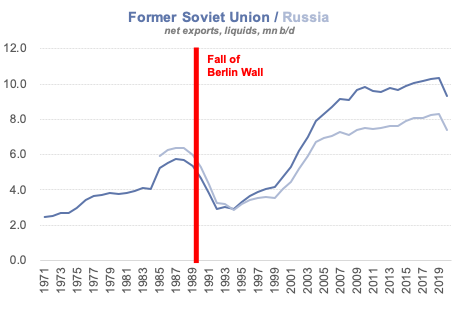

Former Soviet Union: Failed state; Russia: Transitioning to pariah state

The FSU was never a pariah state; I do not think that is the right descriptor for Cold War hostilities. Post the fall of the Berlin Wall, it became a failed state that saw both production and domestic demand decline. Still, net exports fell in half. I suspect that the FSU experience is probably the best analog for what may face Russia. I would also highlight both Russia and the countries that comprised the former Soviet Union as having been on the more successful side among pariah/failed state peers.

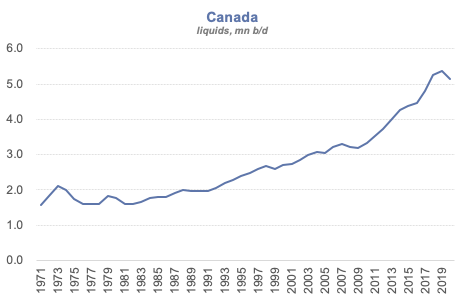

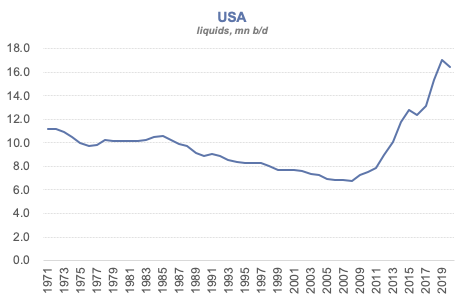

US+Canada should be among the "last barrels" produced during the energy transition

In my view, it makes zero sense for the USA, Canada, or Europe to maintain any physical dependence on Russia or Iran over the long-term. Last week I outlined a path (here) whereby USA + Canada could grow net oil exports by 10 mn b/d by 2030, which would about offset combined oil exports from Russia and Iran. To be sure, there is really not a lot that can be done in the event of near-term (i.e., over next few years) disruption to Russia net exports beyond demand destruction which is very painful as it effectively means recession.

Currently, global oil demand is around 100 mn b/d, of which USA + Canada supplies about 23 mn b/d. Even under particularly strict net zero pathways by 2050, which I do not personally think are likely to be achieved, there would almost certainly be a need for at least 30 mn b/d of oil supply (my personal view is oil demand will be several multiples of 30 mn b/d in 2050). I don't see how its not a national prerogative that the USA + Canada produce the last barrels the world demands for as long as it demands it. The US military protects the world's shipping lanes. USA + Canadian companies can meet the oil needs of their allies.

In contrast to the pariah states discussed above, the friendly states of Canada plus the United States have been reliable oil suppliers.

⚡️On a personal note...

I am sorry to so quickly come back to a previous subject, but I just drove our BMW X5 for another 300 miles and really, really dislike and don’t trust its driver assist function. It’s not good. Our family has three cars (for four drivers): a Tesla Model 3 (my car!), a BMW X5, and a Subaru Forrester, all purchased in 2020 so a fair test of comparative technologies. I would note that BEVs have a 33% share of my family’s new car sales and a 33% share of our car parc, though that is down from a 50% share BEVs had prior to the 2020 addition of a 3rd vehicle. On miles driven, however, the Model 3 is going to be well below the other two cars.

Back to driver assist, the BMW is in third place, in my opion, even lagging Subaru’s “EyeSight” technology. I don’t see how its even a close call on how far ahead Tesla is in this area. Is it because the Model 3 is a BEV and the other two are ICE vehicles? I don’t think that is the reason. Can BMW catch-up to Tesla? You would think so. But why is it so much worse? And what does it say about the time frame by which it will take OEMs to catch-up with Tesla in ramping EV sales? Maybe it says nothing. I suspect it says something that a luxury brand like BMW is nowhere near Tesla on an important future technology. I remain an EV bull and believe they will gain significant market share over the next 20 years for a segment of the market in rich countries.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

🎧 External media appearances

Over the past week I have had the good fortune to appear on The Value Perspective podcast (Schroders), C.O.B. Tuesday (Veriten), and Squawk Box (CNBC). The Value Perspective and C.O.B. Tuesday were long form discussions about the outlook for energy transition at a time of conflict. Squawk Box is a shorter clip where I discuss my preference for a “Super Vol” mindset rather than use the “Super-Cycle” terminology.

The Value Perspective podcast (Schroders) - March 17, 2022

Listen:

C.O.B. Tuesday (Veriten) - March 9, 2022

Watch:

Listen:

Squawk Box (CNBC) - March 11, 2022

Watch:

📘 Appendix: Definitions, Clarifications and Sources

All exhibits are sourced from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2021), IEA, and Super-Spiked.

In all exhibits, I am showing total liquids production (or net exports) which includes crude oil plus natural gas liquids (NGLs), which is the common way to discuss oil markets.

For Iran, Venezuela, Libya, and Iraq, the graphs show annual liquids production. The Russia/FSU exhibit shows net liquids exports (i.e., production less domestic demand).

The stand alone Canada and USA graphs are liquids production. The combined USA + Canada exhibit is net liquids exports.