What The 50-Year Quest For US “Energy Independence” Can Teach Us About “Net Zero” Achievability

Geopolitics and Policy

This past week was Climate Week in New York City. A core takeaway from various meetings not only in New York but also in Oxford, on Zoom and elsewhere in recent weeks is that we continue to see evidence that the general conservations around energy are become healthier and directionally more pragmatic, with “climate only” ideology no longer the overarching narrative. Yes, extremists still exist, their views have not changed, and they continue to make more headlines than is warranted. But the hard-core ideologues no longer dominate the general discussion in the way they did in the 2020-2023 period. We can see this in the current US presidential election, where the topics of climate and energy have not been front and center for either candidate and polls indicate climate is not a top concern for US voters. The continued de-politicization and de-emphasis of energy and climate as a partisan, culture war issue would be a major improvement from where we have been.

With all that said, there is still a debate of sorts on whether “net zero by 2050” should persist as a primary goal. We continue to interact with many people that believe enough new technologies are ready (or near ready) to displace traditional energy sources en masse, and that more forceful policy steps would be the key to getting the world on-track for a net zero future by 2050 or thereabouts. Our core message in all of our meetings has been that everyone on Earth will always first solve for energy abundance followed by affordability and geopolitical security. The combination of those objectives will inevitably lead to new non-oil and gas technologies being developed for regions without sufficient quantities of crude oil or natural gas, as we are already seeing. However, the scale-up factor to fully energize the other 7 (soon to be 9) billion people on Earth to approach (and ideally reach) Lucky 1 Billion People living standards means continued growth in the usage of crude oil, natural gas, and most likely coal for the foreseeable future. Some day that could, and we might even argue will, change. But that day is not for at least several more decades, if not much longer. We do not believe it is possible at this time to know the decade, let alone year, when a permanent peak in oil or natural gas demand will occur.

A counter argument made by more than one person was that the dramatic improvement in US energy trade balances as a result of US shale oil and gas growth shows how quickly the world can change. The logic followed that since this WAS achieved with shale oil and gas, it CAN be achieved with any number of new energy technologies and resources—all that is needed is greater political will to make it happen. We respectfully and wholeheartedly disagree with the analogy and that the key to “net zero by 2050” is simply greater political will.

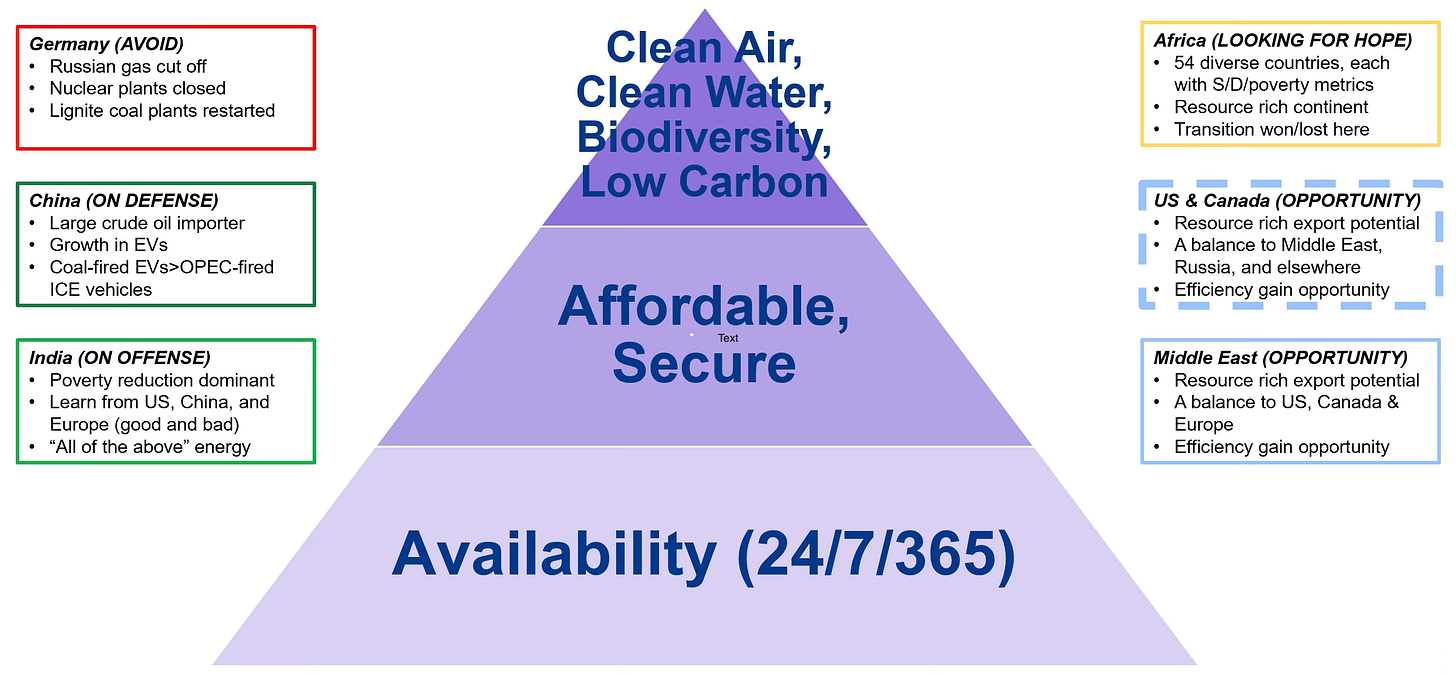

We had considered titling this post “Net Zero Never,” but that would not have accurately reflected our view either. There is little doubt in our mind that energy is best thought of as a hierarchy of needs, with energy abundance 24/7/365 for everyone on Earth the unquestioned direction of travel we are headed (Exhibit 1). Thus far, only The Lucky 1 Billion of Us fully enjoy this abundance, with the other 7 (soon to be 9) billion people making varying degrees of progress. The fact that the developing world is 7X-9X larger than the rich world points to an urgency for those that do not enjoy sizable domestic crude oil or natural gas resources to develop and utilize new energy technologies and sources that will ensure their own energy abundance comes with affordability and geopolitical security (from their perspective). The issue today is the mix of technologies that will profitably scale without significant government subsidies (or taxes) to meet the needs of 10 billion people on Earth is not known. We do accept the lesson from shale that once a viable new technology does materialize, it could scale relatively quickly.

Exhibit 1: We see energy as a hierarchy of needs

Source: Veriten.

Why did US shale oil and gas scale as quickly as it did?

Initial investments were catalyzed by high US natural gas and world oil prices that motivated companies to find new supply sources to meet demand. In other words, there was an obvious profit motive and a belief, especially by many US companies, that they could create significant value for shareholders in pursuing shale (note: we have exhaustively discussed the reality of actual versus expected shale profitability in prior posts). In the US, the combination of private land ownership, a reasonable fiscal regime, significant competition among a large group of companies of all sizes, the lack of a dominant state-owned oil company, robust capital markets, and the application of and willingness to experiment with new technologies, among other factors, led to the miracle that is our shale oil and gas industry.

All of those factors are critically important. Take away any one and we suspect shale oil and gas production would be close to zero today, as we see in most of the rest of the world. Shale potential exists in other parts of the world. It is the unique combination of country, societal, market, and policy factors enjoyed in the US (and Canada) that is invariably not found elsewhere that is the reason for our success in developing the resource.

What role did policy support play in the development of shale?

In contrast to (all?) new energies technologies, there were no subsidies, tax breaks, or other special favors granted US shale producers. No one declared that shale needed to be a certain percentage of US oil or gas supply or any other metric. Shale producers invested within long-standing US fiscal and regulatory frameworks applied to the US oil and gas sector by individual states and the federal government.

The one major policy change that did occur that unquestionably benefitted growth in oil supply was the lifting of the oil export ban in December 2015—an important bi-partisan victory for our country and the greater world near the end of President Obama’s second term. The ban had originally been implemented in 1975 during a time of significant stress following the 1973 Arab oil embargo.

Perhaps most critically, priority or special support was not given to any one oil and gas technology or resource. The market was left to figure out which supply areas should be invested in to meet growing oil demand and respond to then high oil prices. Between 2004 and 2010, a time when oil prices quintupled, almost no one thought shale oil would be the supply answer. Yet, within five years, its unexpected growth contributed to a sustained collapse in oil prices that the industry still hasn’t fully recovered from if its diminished S&P 500 weighting is an indicator.

Looking at all the net zero scenarios we have studied, none of which do we consider to have even a remote chance of being realized, all appear to be assuming that stricter policy choices is the key to a net zero future. The experience of global oil markets over the past 20 years proves otherwise.

Didn’t DOE research contribute significantly to the eventual commercialization of hydraulic fracking?

We have run the ChatGPT query which suggests the answer is “yes.” However, this is not something we have studied firsthand and would welcome comments and feedback from Super-Spiked readers that know more about this topic than we do, as we have been asked a few times about this in recent months. Given that we are otherwise arguing for a negligible policy role in the success of shale beyond lifting of the export ban (which was critically important), we thought it was worthwhile to at least raise this DOE research point and see what we can learn.

If the political goal of US energy independence was (essentially) achieved via shale, why wouldn’t this apply to net zero objectives?

Since the 1973 Arab oil embargo shocked the nation, the following US presidents have called for “energy independence”:

Richard Nixon

Gerald Ford

Jimmy Carter

Ronald Reagan

George H.W. Bush

Bill Clinton

George W. Bush

Barrack Obama

Donald J. Trump

Joe Biden

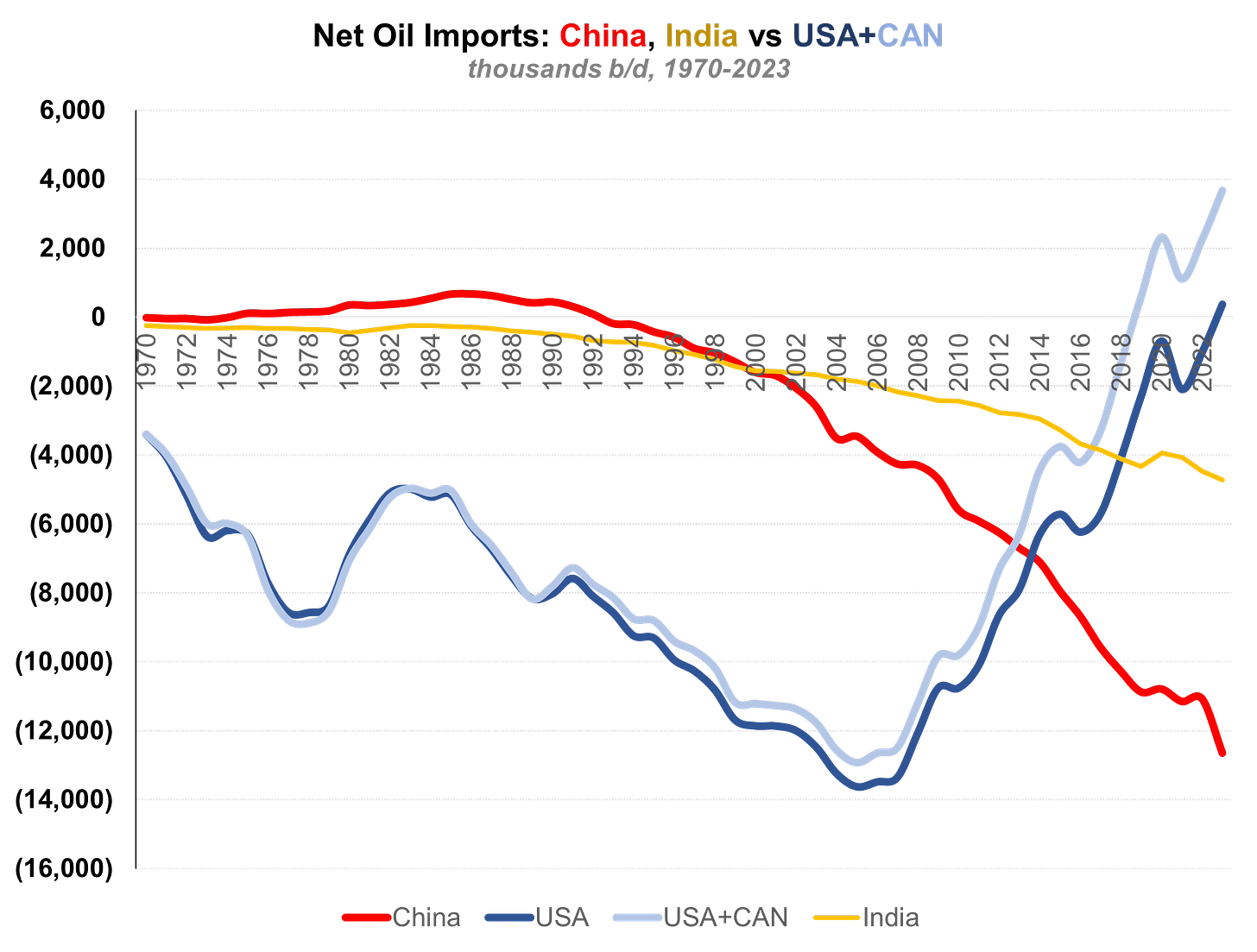

That of course is a list of every US president starting with Nixon. Despite what is clearly a bi-partisan and long-standing national imperative, US oil balances were significantly worse in 2007 versus 1973. Thanks to the shale revolution, we actually became a modest net oil exporter in 2023, a mere 50 years following the original Arab oil embargo and just 48 years after President Nixon called for it (Exhibit 2). In a nutshell, a long-standing, bi-partisan political goal was not achieved until a resource was found that could profitably scale and meet the objective.

Exhibit 2: Since 1973, every US president has called for US energy independence, which didn’t happen until shale came along in the 2010s

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

Before shale, there was no shortage of unsuccessful policy ideas, none of which proved successful in changing oil import trends. An incomplete list includes:

Stricter fuel economy standards to lower demand, which we argue could have worked better if vehicle weight limits had similarly been imposed

Limiting highway speeds to 55 miles per hour to lower demand; turned out that Americans can’t drive 55 (classic video)

Historic electric vehicle aspirations (see California)

Various biofuels policies to promote alternatives to crude oil

Even as recently as 2007, near the absolute oil price peak of the Super-Spike era (the commodities super-cycle of 2004-2014 that is the namesake of this publication), there was zero expectation or awareness that shale oil would be the answer to very tight oil markets. We were at Goldman Sachs at the time and our focus was on the combination of solving for the “demand destruction” oil price and evaluating a host of new supply basins around the world including many deepwater provinces and other challenging locations. We spent zero time in 2007 thinking about the potential for shale oil, which emerged just a few years later.

In fact as recently as 2010, no one imagined shale oil would drive circa 90% of net global oil supply growth in the decade ahead and completely remake global oil markets. By a similar token, in 2015, no one we knew was forecasting a US LNG export boom that would result in the US become the world’s #1 LNG exporter by 2023.

So doesn’t that mean new technologies can scale quickly once proven?

Yes! We should always be vigilant and recognize when markets are in the midst of dramatic change. We should also be humble and realize that going from lab to pilot to commercial scale is hard, with significant uncertainty on cost, timing, and feasibility. At Veriten, we spend a considerable amount of our time evaluating and studying new technologies. It is fun, interesting, and at least thus far, reinforces our confidence in structural oil and natural gas demand growth.

For nearly 50 years, US politicians were calling for “energy independence” and promoting a broad array of insufficient, ill-advised, or unsuccessful policy measures. At this time, we do not believe we know which technologies can scale profitably and quickly to displace the circa 80% of global energy demand derived from oil, natural gas, and coal. It is NOT simply a matter of having greater political will, as is often argued by politicians and activists that are most passionate about addressing climate concerns.

If not from US and EU policy, where will the impetus come from for non-oil and gas technology development?

Despite numerous Excel model-driven “scenarios,” no one knows the answer on how to achieve “net zero” by any year, round number or otherwise, while also and critically solving for everyone on Earth being as energy rich as are The Lucky 1 Billion of Us. Not a single net zero model that we are of aware starts with the assumption that everyone is striving to be as energy rich as The Lucky 1 Billion. It is a fatal modeling flaw.

China, India, and the rest of southeast Asia in particular are strongly motivated to achieve “energy independence” in the same way the US has focused on that objective for all these decades. We eventually got there thanks to shale oil and gas. For the developing world in Asia, we believe they will be highly motivated to crack the code on non-oil and gas technologies, given insufficient domestic oil and gas resources. We just do not know when that will be achieved at a multiple billion persons scale.

How does electrification impact your outlook?

We do not take seriously the climate activist slogan of “electrify everything using only renewables.” That said, there is truth to the idea that power markets are a highly interesting area of focus for both developed and developing markets. In many respects, it is the bridge between those most strongly advocating for energy transition to address the urgent climate crisis (their words) and those like us that recognize that no one on Earth wishes to live without modern energy and all of its benefits, which will always be every person and country’s priority.

China is now the world’s largest oil importer, yet its per capita demand is smaller than Thailand’s never mind South Korea, Canada, or the United States. In a nutshell, China is highly motivated to switch to coal-fired EVs (electric vehicles) over Saudi/Russia/US shale-fired ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles.

From a geopolitical security standpoint, a major advantage of power markets is that once a power plant is up and running, a country can eliminate dependence on the foreign flow of feedstocks if it is solar, wind, nuclear, or geothermal or if the country has domestic coal or natural gas. “Electrify as much as you can with a diversified power grid” is a less catchy slogan but likely closer to the reality of what many countries will pursue. Power grids present their own risks, but large negative oil trade balances and the geopolitical exposure that comes with that is not one of them.

Is there a role for traditional energy to participate in power markets?

We are spending as much time thinking about this question as any other. Global gas opportunities are clearly an avenue toward power market participation. Figuring out ways to partner with Big Tech to support data center growth is a related avenue. How about joint ventures with merchant power producers that may lack the balance sheet heft enjoyed by large-cap traditional energy? Is there a geothermal or nuclear angle for traditional energy? What opportunities, if any, exist to partner with foreign countries in their power markets? Retail electricity classically requires a very different culture, mindset, and skillset than traditional energy development. But the growth opportunity appears to be significant. Figuring out how, if at all, to participate is one of the challenges we are spending time thinking through.

🎤 Streams: Wicked Energy podcast

This past week Arjun joined host Justin Gauthier on his Wicked Energy podcast, where they discussed the outlook for China oil demand and broader energy mix, the prospects for peak global oil demand, navigating oil price volatility, and the upcoming election. The 41 minute episode is linked here.

⚡️On A Personal Note: A good bogey on 18 at Carnoustie

As anyone that watched last week’s Super-Spiked videopod can surmise, I had the great fortune of making my ninth pilgrimage to The Home of Golf. There is no place I would rather play golf than in Scotland. The people are super nice. It is a dog friendly culture. And the idea that all courses should be accessible to the public is a perspective I very much appreciate.

In ranking my favorite golf courses anywhere in the world, I now have Carnoustie’s Championship Course as number two only to The Old Course. I was fortunate to catch Carnoustie on a day there was no rain, not too much wind, and the fescue/gorse was mostly cut down. It is a course I can’t wait to get back to as I would have played a few holes differently, and I also think I won’t be as amped up on those first 5 or 6 holes where at least three 100-130 yard shots after good drives were met with too much adrenaline and not enough smooth touch.

After a strong start, an up and down stretch on holes 7-13, I was happy to have played to bogey golf on holes 14-18. Putting has been a season long issue and I was in a position to have been only 1 or 2 over par over that stretch had I not missed ALL makeable putts. My favorite shot was on the 18th hole. I had 190-195 yards into the wind from the fairway, but over the (in)famous burn to a center-right pin. Neither the caddy nor my playing partner were going to let me lay up in front of the burn. I smoked a 5-wood that landed pin high in the greenside bunker. One of my better sand shots put me 10 feet from the pin. But I settled for bogey after burning at least my fifth edge that round.

Carnoustie’s 18th hole

Source: Super-Spiked selfie.

If you are fan of The Open Championship (aka The British Open), you will know the story of Jean Van de Velde and his experience traversing the 18th hole at Carnoustie in 1999 with a seemingly commanding 3-shot lead (1999 British Open at Carnoustie). The BBC announcer brilliantly expresses concern starting from the tee shot. “His golfing brain stopped about 10 minutes ago. What are you doing? What on Earth are you doing? Would someone kindly go and stop him. Give him a large brandy and knock him down. This is really beyond a joke.”

To his credit, after a series of unfortunate shots that led to his 3-shot lead evaporating, he holed a tough 7-foot putt to make it to a 3-person playoff, which he eventually lost. In July 2018, Mr. Van de Velde gives a great explanation of what he was thinking with his shot selection (Jean Van De Velde Relives THAT hole in 1999). His mindset was to play to win. He was not looking to play defensively with a big lead, as given the conditions and the nature of the course, he did not believe that there were more conservative shots to be played that would have ensured a better outcome.

In the end, he didn’t win. But his story will go down as one of the most memorable holes played in golf history, perhaps because he did not end up winning. “I will always be very at ease with what happened. The 2 or 3 days following I was a bit distraught. But…you realize you are one of the lucky guys to walk inside the ropes. If you lucky enough, you make a very healthy living doing what you love. Not many people have that luxury. I have always felt very privileged. I have no right to complain. At all.” I have nothing but respect, admiration, and empathy for Jean Van de Velde.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

I would suggest a small improvement in precision, Arjun. Private land ownership is relevant to the rise of shale oil, among other extracted resources. But what really matters is private ownership of mineral rights.

DOE certainly spent money on the “shale revolution” but mostly with the biggest companies who were late to the dance. The rest of us simply succeeded by trial and error… more error than success early on, but eventually we cracked the code.

Lab research is really only effective when you have adequate input parameters for your modeling. When it came to shale, that simply didn’t exist because it had never been exploited before. It took rolling up the sleeves and spending/destroying a lot of capital to figure it out.

Fortunately, much can be learned from those lessons and apply it globally. Vaca Muerta we’re looking at you!