If a young analyst could have a CEO hero, for me, it was Lee Raymond. Like all of us, this is not a claim that he was some sort of perfect human being; nor was he even a perfect CEO. I was scared to death of him. We all were. But he is one of only a small group of energy leaders that has demonstrated the ability to generate outsize returns through superior capital allocation over long periods including both good and bad times for the sector. We should all have capital allocation heroes: Lee Raymond is mine.

During one of my first visits to Asia in the 1990s, our analyst group met with the Exxon team that was evaluating a natural gas project area in China that was being broadly sought out by foreign companies; it was perceived by the market as an entry play into a key future region. Exxon could have easily outbid rivals and secured the opportunity. It chose not to. And I can still remember the Exxon Asia executive's explanation (paraphrasing): "I will not be the person that has to some day go to Dallas to explain to Lee Raymond why I am taking a write-off on a project that wasn't likely to be profitable at the get go and had no clear synergies to any future opportunities."

A core focus of Super-Spiked’s corporate strategy analysis has been the idea that traditional energy companies should look to pursue strategies that will ultimately drive S&P 500 leadership and separation from the mass of companies that simply trade up and down with commodity prices and sector averages. No company better exemplified this approach than Exxon under legendary CEO Lee Raymond, who held the position from 1993-2005. This post is dedicated to his legacy of sustained top quartile performance during both the lackluster commodity price environment of the 1990s and Super-Spike era of the 2000s. When contemplating strategic and investment decisions, we might all be well served to ask: What Would Lee Raymond Do (WWLRD)?

With this week's post, I would also like to start the process of better differentiating between top quartile companies and the sector more broadly. In my view, the importance of being best-in-class versus merely average is particularly relevant when there is general economic and market turmoil. Everyone looks good in a bull market; it's the more challenging periods where true greatness is revealed.

Given Mr. Raymond’s unquestioned focus of being an S&P 500 leader, I am not sure there is a more interesting thought exercise than to consider how he would run a contemporary super-cap traditional energy company in the messy energy transition era we find ourselves in? Yes, I know, Mr. Raymond is often vilified as the face of oil company "climate denialism”, a term I have come to despise given it is being applied to anyone that doesn't fully submit to the now mainstream "anti-fossil fuel, counting CO2 is all that matters, electrify everything but only with intermittent resources" ideology. I am not going to prosecute that case in this series of posts. In this note I will provide some grounding views on Mr. Raymond's legacy as CEO. In future posts, I think it could be fun to run through some current examples and ask: What Would Lee Raymond Do?

Exxon under Mr. Raymond was a leader in crude oil, natural gas/LNG, refined products, and petrochemicals, helping create available, affordable, reliable, and secure energy all the world depends on. May God Bless Lee Raymond for his contributions to helping literally fuel global economic growth, which is critical to reducing global poverty and improving environmental outcomes.

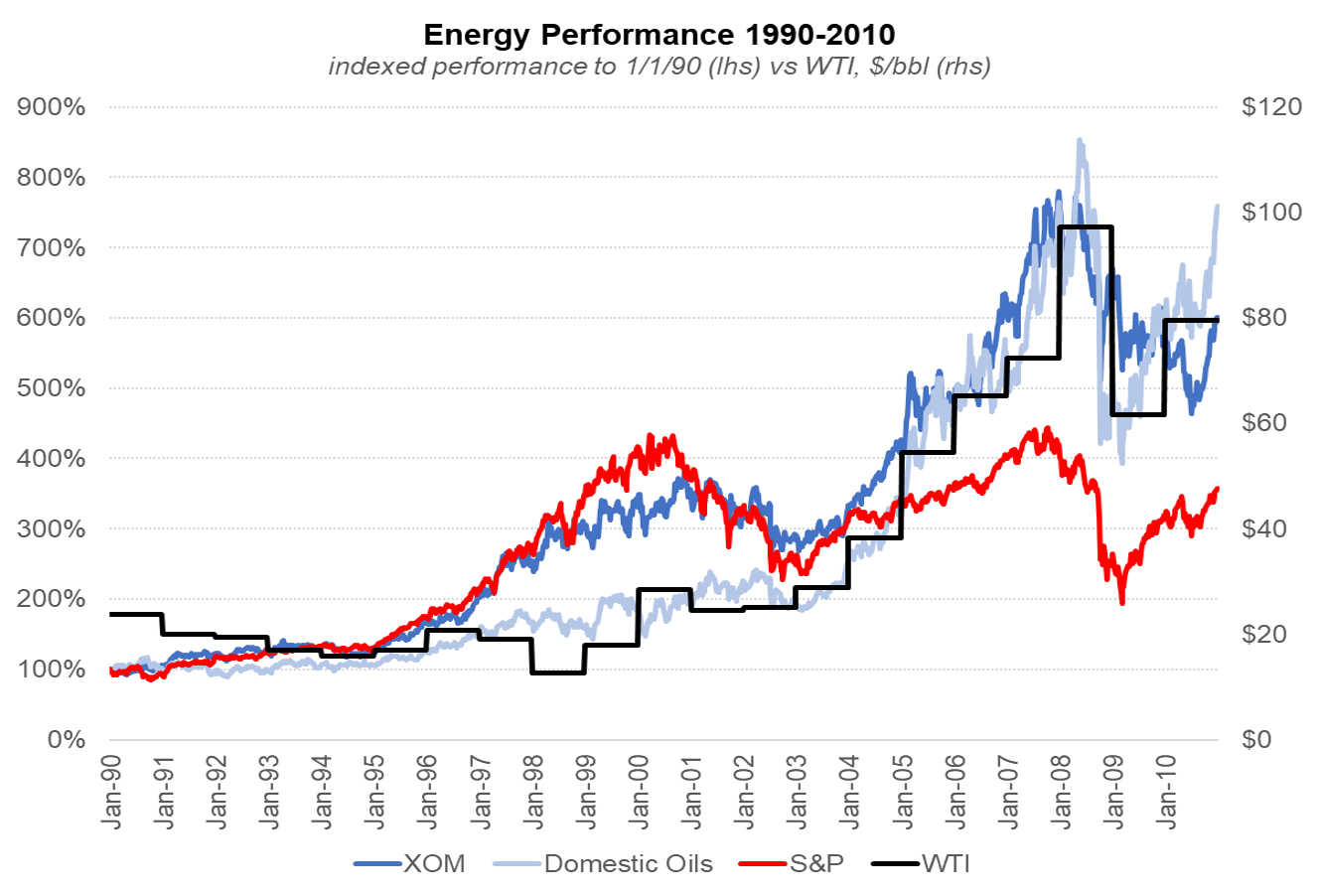

Exxon kept up with the S&P during lackluster 1990s...and massively outperformed during the 2000s super-cycle era

In the 1990s, if there was one traditional energy stock that was must own for generalist portfolio managers it was Exxon (pre Mobil merger). By focusing on (1) superior ROCE generation rather than volume growth metrics, (2) a fortress balance sheet, and (3) returning excess cash to investors, Exxon shares kept pace with the S&P 500 during a challenging period for the sector, consistently ranking as a Top 3 holding in the S&P (Exhibit 1). This was a period when WTI oil prices were range-bound between $15-$25/bbl (nominal) and traditional peers went sideways (Exhibit 2). On ROCE, it wasn't a close call in terms of Exxon's dominance versus the sector (Exhibit 3).

The Super-Spike era of the 2000s lifted all energy boats to outperformance versus the S&P 500. ExxonMobil (post merger) kept pace with peers and smashed the S&P 500. For sure, there were niche players that outperformed ExxonMobil in the bull market. That is the nature of what will work in a commodity super cycle.

Exxon's long-term outperformance bears some reflection: It kept pace with the S&P 500 when oil was going nowhere in the 1990s and crushed the S&P 500 during the structural bull market. For long-term investors and for managements looking to create viable going concern enterprises, in my view, legacy Exxon is the role model on how to do that. In the shorter-term, defined as <5 year periods, there are always niche players that offer the opportunity for outsize returns. Those are opportunities private equity and traders might look to pursue. For sustained, multi-decade outperformance, I'll take the legacy Exxon model.

To be clear, in the short-run—days/weeks/months/quarters—commodity prices will heavily influence share price performance. This was true for Exxon as it was for the rest of the sector. But for those of you that can look beyond your screens, it's worth studying Exxon's great history.

What went wrong in the 2010s?

I would argue in a nutshell that ExxonMobil did not evolve post Lee Raymond's tenure. His playbook worked for his era. Companies don't move forward based on pre-determined force and momentum. It is about people making judgments and decisions. And as the impact of (less successful) decisions made by Mr. Raymond's successors began to weigh on the company, Exxon's century at the top of the heap was undermined.

A fuller analysis of Exxon's downfall is for a different post. If I could sum it up to one issue: a lack of diversity in the types of people and their thought processes and perspectives that rose to the top at ExxonMobil. Hopefully everyone knows by now here at Super-Spiked I am not referring to the check-the-box, virtue signaling variety of diversity, but rather substantive diversity that I think is a critical success factor for long-term going concerns.

What Did Lee Raymond Do?

A common misperception among the old crowd that knew Exxon in its glory days is that it was all about minimizing capital spending and maximizing free cash flow and ROCE. This is an inaccurate characterization in my view. For sure Exxon did not pursue the aggressive volume growth targets just about all peers sought; by not doing so, I think it created the impression Exxon was uninterested in reinvestment. This is also not true.

I'll paraphrase Mr. Raymond from what are vivid memories of his legendary analyst meeting speeches: "We are not trying to guess oil prices. We have a long history of proving that is not something we can do. Rather we are looking to invest in all projects that will be at the low end of the future cost curve. Our production will be an outcome of this process."

Five lessons from What Lee Raymond Did

Lesson #1: Stop using oil price guesses to justify growth CAPEX

A typical oil company will use a long-term commodity price deck (either their own estimate, the forward curve, or based on market experts) to screen projects that generate IRRs above their hurdle rate.

Guess what: as oil prices rally, companies raise their price decks and more projects screen well, especially when using old cost estimates.

This is the cardinal E&P investment sin: My project will retain the cost structure from the bear market and the higher oil prices will help us generate good returns (we’re also going to ignore execution risk, fiscal regime risk, labor productivity risks, etc., etc.).

Lesson #2: Using a conservative deck is better than an optimistic one but isn't the point either

A counter to Lesson #1 was to simply use a perpetually conservative price deck. Frankly, this was the mistake Exxon may have initially made post-Lee Raymond and most super majors made during the 2002-2008 portion of the Super-Spike era.

They did not invest for fear of Lesson #1.

Yes, it's better than being too aggressive, but its not sustainable either as they all found out.

It’s not sustainable because to be a going concern oil and gas company, you have to reinvest even to simply maintain production; oil and gas fields natural deplete.

The goal isn’t to be super conservative at all times. There is a need to take risk. This is a point many public equity investors I think forget in the early days of a new upcycle.

Lesson #3: You are trying to invest in projects that will be at the low end of the future cost curve

Key point: Sustainable outperformance requires investment...it just has to be constrained to projects that will be at the low end of the future cost curve.

The future cost curve is not definitively knowable in advance, it requires human judgment.

It's the oil industry version of the Wayne Gretzky line: You need to skate to where the puck will be, not where it is or was. You also are not remaining stationary in the middle of the ice. Or playing five defensemen and a goal tender. A prevent defense does not win games. And all similar cliches.

It's obvious now and was back then as well: the greatest investment I believe Lee Raymond made was the merger with Mobil. At the time, Mobil's highly profitable legacy Arun natural gas/LNG field in Indonesia was in decline and the company’s overall outlook cloudy. Mobil was an early entrant to what was perceived at the time to be a higher risk, higher cost new LNG play in Qatar. Lee Raymond took a calculated risk that Qatar LNG would be at the low end of the future cost curve: He was right 1000 times over.

Lesson #4: Opportunities materialize when they materialize and you have to be ready to pounce

Prior to the Mobil merger, there was no indication that M&A was going to play a role in Exxon's future. We all thought they had sufficient captured resources to sustain the company for quite some time.

It's possible that stand alone Exxon would have been fine without Mobil. But there is little doubt that they were much better together with areas like Qatar far superior to the LNG opportunities Exxon would otherwise have pursued.

Strong ROCE, a fortress balance sheet, and a premium valuation based on investor confidence in Exxon’s ability to allocate capital positioned Exxon to combine with Mobil and to become the surviving post merger management team.

Lesson #5: For large companies, S&P relevance matters

Let me start with the opposite, you can be a really successful niche E&P if you capture the right resource opportunity at the right time with the right people and do exceptionally well. That is not the point of this post or sub-comment.

For large-cap companies, there is a relevance to being a Top 25 S&P 500 holding rather than a smaller, less relevant positioning.

It matters that generalist portfolio managers have to care about the tracking error of not owning your stock. It greatly reduces the risk that virtue signaling can win out over substance.

⚡️On a personal note…

I was deeply saddened to have heard the news of the sudden passing of Steven Chazen last week, a legendary energy executive for his role in transforming Occidental Petroleum from a mess of an also-ran to leadership status in the late 1990s and 2000s. Long-time Super-Spiked readers will recall that Oxy's acquisitions of Altura Energy and Elk Hills in the late 1990s were the inspiration for my first Dumb Calls I Made As An Analyst post.

Mr. Chazen's approach as an energy executive bore some similarities to Mr. Raymond's, albeit with a slightly more approachable personal style. Neither suffered fools. Mr. Chazen seemed to enjoy the debate with analysts; Mr. Raymond could not hide his contempt for the less thoughtful among us.

I believe the most fruitful period of Mr. Chazen's Oxy career was the turnaround era when he was essentially the CFO/numbers guy balancing Dr. Ray Irani's ambitions as CEO. Most of us I don't think really appreciated it at the time—and I know I will get grief for saying this from my peers from that era—but together they were a great team. In my 30 year career, Oxy's whole-sale transformation from worst-to-first has to rank at or near the top of the list of all time great corporate turnarounds.

Putting stock performance aside, I loved dealing with Steve 1:1. He was very engaging and quite funny with his dry, sarcastic sense of humor. He made me a better analyst by constructively challenging "what I knew to be true" and doing so in a way that really made me think through my assumptions and preconceived notions. It was a different version of what made Exxon great—Steve Chazen styled.

May God Bless Steven Chazen for all of his contributions to helping fuel global economic growth, the benefits of which we all enjoy. Rest in Peace.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Hello Arjun,

I am definitely looking forward to posts about how Lee Raymond would manage today's super vol environment!

I've thought a lot about your discussion regarding the relationship between ROCE and the oil price. Lee Raymond focussed on ROCE throughout the cycle and particularly at the lower end of the future cost curve, or to use Darren Woods' favourite expression, "investments that are robust throughout the cycle" (i.e. Lesson #3).

Nerding out on one thing: I keep coming back to the definition of 'super volatility' - what does 'super volatility' precisely mean? Please clarify, but I think you mean that the cycle's peak-to-trough demand-destruction to shut-in prices remain the same, the dynamics that drive them (inelasticity of supply and demand) remain the same, but the key change in this cycle is that the frequency of the peak-to-trough waves have increased dramatically. We still go through the same boom-bust cycles as in Lee Raymond's day and for the same fundamental reasons (in our case that supply is choked and no swing producer), but instead of the archetypal cycle taking 5 - 7 years as in his day it's now only taking 1-2 years. Super nerdy definition: the amplitude of today's cycles are the same, but wavelength has decreased dramatically (?).

From an investor's point of view, we are now experiencing these boom-bust cycles in fast forward, which feels like super-volatility to us.

Here's the issue: in Raymond's day his cycle's wavelengths were longer, it allowed the ROCE effect to outweigh the volatility effect over time. But in this super-vol cycle if you invest $1B in Project A at crude price of $70, the bust could come a year later and the project looks like a terrible investment, yes, it could recover quickly on the crude price upswing but it's REALLY stressful to manage capital in this kind of environment, the ROCE seems almost beside the point if you're watching the value of the project swing violently every few months as crude prices shoot up and down.

Question: where does this leave capital allocators? WWLRD? We need to invest and plan CAPEX and the supervol swings cause a lot more headaches today than in Raymond's day. The only approach I can think of seems to be to have a set of top-quartile type investments ready to invest in and wait until the cycle is at an apparent peak (~$120+, to sell, to sell short) or trough (~$30-, to buy, to invest in), rather than risk making investments somewhere in the middle (~$70), because the cycles are so quick today that investing in the middle is too uncertain and another peak or trough will be along soon enough where you'll have a better idea of where you are in the cycle (hard to make a bad call investing in a top quartile type project/company at $30/barrel). To summarize: the super volatility effect has become so large that it feels like it is now outweighing the ROCE effect and so it is forcing us all into being cycle-timers even if we don't want to be. WWLRD?

Best,

J

I remember a meeting once where Lee Raymond spoke at the Council of Foreign Relations. He was trying to make the point that most people don't have any idea of the scale of the oil business. To illustrate, he said (paraphrasing) "think of those one gallon containers that people use to get extra gasoline ... now line them up end to end. ONE DAY's oil consumption measured on one gallon containers would go around the world THREE TIMES." Still remember it to this day. 100 million barrels a day is a lot of energy ...