In the May 21, 2022 edition of Super-Spiked, Market corrections, recession risk, and energy, I examined how energy traded during the notable market sell-offs of the past 30 years; in a nutshell, energy was not immune on an absolute basis though both the magnitude and relative performance varied with the broader circumstances driving the downturn. In this issue, I take the analysis back to the 1970s. If you want to skip the remaining 2,000 or so words, the punchline is that energy equities were not immune from being crushed in the brutal 1973-1974 bear market and recession despite a tripling in oil prices. I offer this not as a recession warning—and definitely not as a trading call—for the current period, but rather to simply recognize the history that energy equities can fall, potentially meaningfully, even if you are at the start of a structural bull market as was the case in both 1973-1974 and 2000-2002. As an investor, board member, or corporate management, the question as always is how do you prepare for and take advantage of inherent volatility in financial and commodity markets.

I would note that the May 21 post covered my career, which I believe benefit my conclusions given the first hand experience. While this post is still within my lifetime, I was not actively trading the market or energy stocks during grammar or nursery school. As such, the quality and possibly the accuracy of my conclusions regarding that era is likely lower than what I directly experienced.

From the May 21 post:

...traditional energy is not immune from recession [concerns], with downside risk to both oil prices and oil equities likely in the event recession does materialize. However, 20 years ago, it was not at all obvious or expected that a new super-cycle was around the corner. This time around, the combination of limited enthusiasm for a major CAPEX cycle from anyone (investors, industry, policy makers, politicians), the long-term negative outlook for Russia oil supply, and the fact that oil demand ex-recession is not on-track to rollover anywhere near as quickly as climate die-hards would lead you to believe, all point to an eventual resilience to traditional energy versus broader indices in the event recession does materialize.

Moreover, the better historical analog is almost certainly the stagflationary 1970s than the booming global growth of the 2000s. Oil prices did not trade freely in the 1970s (pre-NYMEX) and only the names of the integrated oils would likely be recognizable to most current investors. But the very concept of stagflation (stagnant economic growth but high inflation) comes from that time period. Arab Oil embargoes seem unlikely. But Russia turning into a pariah state is likely just as disruptive if not more so.

I have to say that I am somewhat surprised to see that a closer examination of the 1970s environment does not change some of the broad conclusions I made about the more recent 30 years. There were also a few surprises:

Energy equities are indeed not immune from recession risk, even if it is spiking oil prices contributing to economic and inflation concerns. The 1973-74 recession and bear market overwhelmed any benefit energy equities received from a then unheard of tripling of oil prices.

It was not until investors (apparently) gained confidence that the rise in oil prices was "sustainable", or, perhaps more accurately, were unlikely to reverse any time soon, that we saw material and sustained outperformance in the back half of the 1970s.

Bad economic, energy, and inflation policies, like we saw during the Nixon price control years were apparently as bad for energy equities as for other sectors, offsetting for energy equities the benefit of higher oil prices.

Energy equities performed really well during the Jimmy Carter presidency before cratering during Ronald Reagan’s 1st term. For those of you that believe Joe Biden is a modern Jimmy Carter, perhaps this bodes well that the next Ronald Reagan may finally be around the corner?

Buy-and-hold versus active trader

As I have stated previously, my interests have long resided in trying to call the structural (i.e, long term) energy cycles. The shorter-term ups and downs is what dominates 99% of the conversation in the media and among investors, politicians, public policy makers and the general public; it is not the focus of Super-Spiked.

I define "short-term" as the daily, weekly, monthly, and quarterly trading dynamics. I would define long-term as multi-year to decade long in perspective. The tricky time frame is the in between 12-24 month period. Let me use an example.

If you purchased a 50%/50% basket of Exxon and Chevron shares at the start of the 1970s and held until the start of 1981, you were up 236% in absolute terms versus the 47% increase in the S&P 500 (all figures exclude dividends).

However, from the S&P’s peak at the start of 1973 to its October 1974 trough, that same 50%/50% Exxon/Chevron basket fell by 44%, about in line with the 48% drubbing the S&P 500 took.

Individual investors will have to make up their own minds as to whether they can or would want to endure that magnitude of drawdown if they are confident in the long-term upside; it's easy in hindsight to say you should look through the volatility and buy-and-hold or to believe you can reasonably time the shorter-term peaks and troughs. This post offers zero advice or insight on what you should do; there are plenty of experts you can look to on Wall Street and Twitter actively engaged in the day-trading battle.

While there are fund managers who have strong track records of shorter-term trading, my personal biases tend toward the longer-term buy-and-hold model when in a structural upcycle. However that doesn't mean I ignore or don't react at all to the shorter-term movements. The Street analyst lingo might refer to this as trading around a core position.

For companies, the question of equity market volatility has implications for M&A and share repurchases. I have long advocated for a fortress balance sheet that would allow a company to not only survive but thrive through a downturn, with trough of cycle M&A infinitely more possible from a position of balance sheet strength. It is unheard of for companies to engage in large stock repurchase programs at trough stock prices—theoretically the best time to buy your shares. Share buybacks, unfortunately, tend to be pro-cyclical, with investors and analysts complicit in this reality. I accept the fact that it is very difficult to authorize a large repurchase program at the trough; so all I ask is companies be mindful about at least trying to buy more shares on pullbacks rather than chase rallies—akin to trading around a core position as an investor.

What are the main 1970s risks that could be repeated? Bad government policy reaction tops the list

While a deep, global recession would seem like the obvious answer to what could drive say a 50% correction in the S&P 500 AND energy equities, I would argue that government policy risk is an important corollary driver to generic economic weakness. In the United States, we fortunately have a lack of a clear majority for either major party, which in theory should limit the risk of really bad government policies being enacted. But I can't even type this sentence without my market instincts recognizing that politicians from either party can always make things worse...so no promises here.

Europe has already shown the significant economic and humanitarian harm bad government policies can do via what is a mostly self-inflicted major energy crisis environment. Has Russian President Putin made things worse? Sure. But it is a pretty ridiculous mis-direct to believe he is the over-arching reason Europe finds itself on the precipice of an energy disaster. The policies that have led to this are self-inflected via ill-advised "climate only" ideologies having gone mainstream. An over-reliance on growth in renewables, the early retirement of nuclear power plants, the disincentivizing of domestic oil & gas production and infrastructure, and a resulting over-dependance on Russian oil and gas I would attribute as the key factors driving Europe's energy crisis. No country or region in any other part of the world should look to follow any aspect of European energy and climate policy.

For buy-and-hold energy investors, what are the similarities and differences with the 1970s?

On the positive side, there is currently no appetite among investors or sector management teams for a major new CAPEX cycle. Ultimately, every prior structural oil upcycle has ended with a CAPEX boom. This one may too as well, but we are currently much closer to trough rather than peak CAPEX.

We currently have a much broader swath of energy companies than I would ever have dreamed of committed to returning excess cash flow back to investors. This (positive) behavior was historically limited to the major integrated oils; it is now broad-based. It is possible if not inevitable this will revert back toward more CAPEX, though there are no signs of any behavioral change yet.

The commitment of oil and gas companies to return excess cash back to investors suggests there is captureable value of future upside price risks; in other words, oil and gas equity valuations should benefit not merely from higher prices but the value inherent in otherwise transient price spikes.

Government policy risk remains high; it's hard to guess the bad decisions policy makers will make ahead of time; at least in the United States, we can have hope that gridlock counters the extremists on either side and slow compromise prevails.

Oil prices did not freely trade in the 1970s; as such the notion of short-term volatility didn't exist in the same way; I would suspect that means equity volatility will be higher in the current era.

The last two super-cycles came with a big test for Energy bulls

An obvious conclusion when looking at the last two super cycles—the 1970s Arab Oil Embargo era and the 2000s Super-Spike era—is that both came with a significant test of will on the part of energy investors relative to the otherwise bullish structural trend. Said another way, both experienced a significant drawdown for energy equities.

Exhibit 1 shows my prior analysis of major corrections over the past 30 years. The period that I think is most similar to the current is the Internet Bubble burst from the March 9, 2000 NASDAQ Composite peak to the October 4, 2002 trough. This period immediately preceded the Super-Spike era and was several years after the December 10, 1998 structural crude oil trough of $10.72/bbl. Energy (as measured by the S5ENRS Index) meaningfully outperformed the NASDAQ and S&P 500 though notably still declined in absolute terms.

In this post I have taken a closer look at the 1970s. Exhibit 2 shows two measures of energy sector performance. I created an Energy Sector index comprised of equal weights for Exxon, Chevron, Mobil, Texaco, Atlantic Richfield, Occidental Petroleum, Phillips Petroleum, and Schlumberger. I also show a 50%/50% basket of just Chevron and Exxon. Versus the S&P 500 peak in early 1973 to its October 1974 trough, the S&P fell 48%, the energy sector index declined 35%, and the Chevron/Exxon basket fell 44%. This occurred against the backdrop of a completely unexpected tripling in oil prices as OPEC attempted to gain control of oil markets and in reaction to conflict between Israel and its Middle East neighbors.

I would note that in the current period, despite pulling back from early June highs, energy equities are still up a meaningful 43% (through August 17, 2022) since the recent NASDAQ Composite peak on November 19, 2021 (Exhibit 1). It’s a complete outlier from all prior major market corrections including the Internet Bubble burst and the 1973-1974 recession. Let me be clear, I am not making a bear call on energy equities; splashy timing and trading calls are neither my forte nor interest, which I will leave to others. I am simply observing that even in energy super-cycles, the equities have historically faced serious tests along the way including significant declines on an absolute basis. It’s not a question of arguing “why this time is different”; it’s about being prepared for inherent volatility in the context of one’s long-term view.

⚡️On a personal note…

I don't think it's a controversial or partisan statement to declare most Americans view Jimmy Carter's presidency as completely forgettable and among the least successful over the past 50 years. I remember waiting in gas lines with my parents. And the low point was surely the failed rescue of the American hostages held by Iran. The era came with a lot of pain. But here at Super-Spiked we try to stay positive, non-partisan, pragmatic, and balanced. So let's focus on what were some all-time great positive developments that occurred during the Carter Administration:

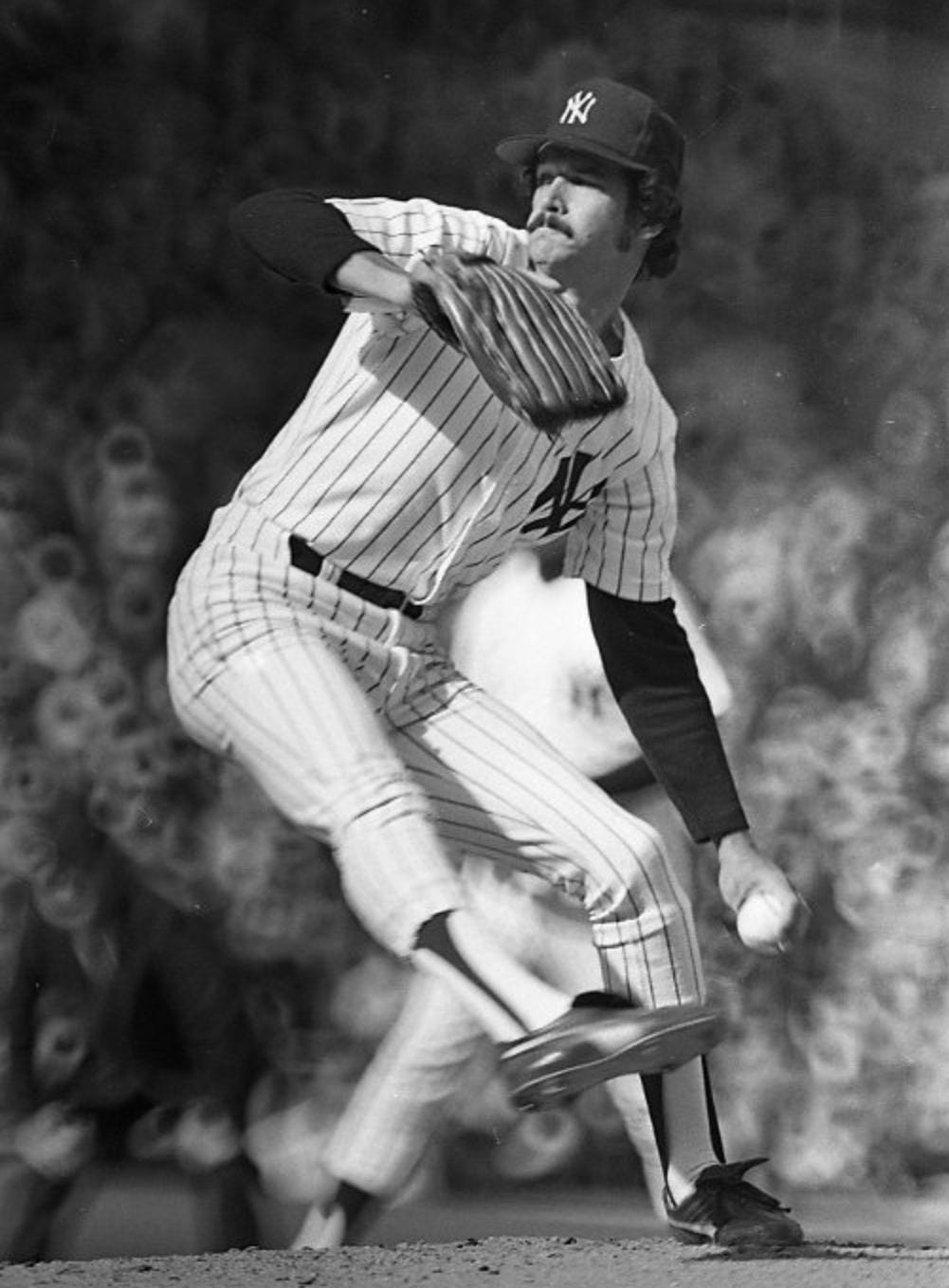

The greatest sporting franchise in the history of the world won the 1977 and 1978 World Series. Sadly for modern day Yankees fans, Gerrit Cole is no Ron Guidry. Boone ain’t Billy and Hal is a far cry from George.

My all-time favorite movie, Star Wars, was released on May 25, 1977.

AC/DC released what I consider to be their greatest album Let There Be Rock on March 21, 1977, with the title track the latest addition to the Super-Spiked Energy Transition Playlist. Let There Be Rock was followed by the under-appreciated Powerage and the better known and now mainstream albums Highway To Hell and Back In Black. Think about that: four of AC/DC's top 5 albums per my ranking all came out during the Carter years! Yes, AC/DC is an Australian band. But if you don't make it in America you haven't made it anywhere and it all occurred during the Carter Administration.

Do many Americans alive in the 1970s wish President Carter had instead led a different country in a galaxy far, far away? Undoubtedly. But if President Biden wants to take credit for the recent gasoline price decline, why shouldn't historians give President Carter credit for overseeing two Yankees championships, the release of Star Wars, and the rise of AC/DC. Cause and effect and all.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Regards,

Arjun

Thanks for your comment Weston. My personal view is that we won't see a 50% drawdown in energy equities. The thing that jumps out to me is that energy equities are up massively vs the broader market being down. If the broader market collapses (not my call...but a possible scenario), the point is that I think it will be tough for energy still be in positive territory. Of course no cycle is identical and ESG and "don't invest in CAPEX" this time around was not seen previously. I do happen to agree with your broader conclusion that "one might expect oil and gas stocks will do better than they did in the 1970s..."

Hi Arjun,

Thanks for another wonderful column.

About a year ago, I read a few Twitter posts by an old guy who claimed to still have hard copies of old stock chart books (of pre internet era). Unfortunately, this was more than 10 months before I established a Twitter account. I forgot his twitter name and did not bookmark the link. Anyway, he made three observations based on his old chart book on the performance of the energy sector for the decade from 1970 to 1980.: 1) the index of big oil companies (IOCs) was the worse performer, with only ~150% return; 2) the US domestic producers did much better, with ~ 700% return; 3) the equipment and service index had the best return, up ~2000% (yes 20 times!). He even posted an image of the equipment and service chart which have I saved on my PC. I was intrigued about it and tried to verify it myself. I even went to my local libraries to look for old stock chart books. Unfortunately, I do not have any lucks.

The under performance of IOC in 1970s is understandable . A lot of their foreign assets were nationalized by some OPEC countries. The US dollar also weakened against many foreign currencies due to Nixon's action of not honoring Brentton Woods agreement, which pushed up the production cost of IOC's remaining foreign assets relative to the domestic assets.

The out performance of OFS in 1970s is somewhat surprising. The OFS got hit much harder than E&P in last 8-10 years. The recovery of OFS so far has lagged behind of that of E&P. So, it seems that the sector has some setups for the out performance in the current cycle. It may actually happen if the policy of green energy transition and decarbonization becomes more practical.