Last week we addressed three of the Five Big Calls To Get Right Over The Next Ten Years (here). This week we turn to the fourth one listed: policy risk, in particular if a future "Super Spike 2" energy crisis environment were to materialize.

As a reminder, our initial list of Five Big Calls To Get Right Over The Next Decade included:

OIL: What comes after Tier 1 US shale oil?

GLOBAL NATURAL GAS: What does European natural gas demand look like a decade ahead?

NEW ENERGIES: Where, when, how, and whether to gain exposure?

POLICY: How to navigate energy policy uncertainty?

VOLATILITY: What is your framework for embracing commodity macro volatility and path uncertainty?

Policy risks are global in nature and broad-based. In traditional energy, it is usually assumed that such risks are negatively skewed, including the possibility of higher taxes, unfavorable contract term changes, expropriation, project approval delays, and so forth. In a few cases, positive developments are possible when thinking about things like new country openings and the rare but not unheard of favorable fiscal/tax reform.

This post is not intended as an exhaustive discussion of every possible global policy risk. Instead, we focus on two negative risks and one positive one that we think are not receiving sufficient attention but could be quite material to companies and investors over the coming decade.

If Super Vol turns into Super Spike 2, will a future US administration be tempted to restrict energy exports?

How does pressure on financial services firms to align financing and insurance exposures to a "Paris-aligned net zero by 2050" pathway impact western oil and gas companies?

Which countries could improve contract terms to attract foreign investment?

When does "Super Vol" become "Super Spike 2"?

We believe adverse policy risk in general increases for the traditional energy sector as commodity prices rise. We saw hints of this in 2022 when oil prices initially rose above $100/bbl. It makes one wonder what the reaction will be if oil prices were to rise by a factor of 5X or 10X (as opposed to the initial doubling post Russia-Ukraine) as we have seen in past super-cycles.

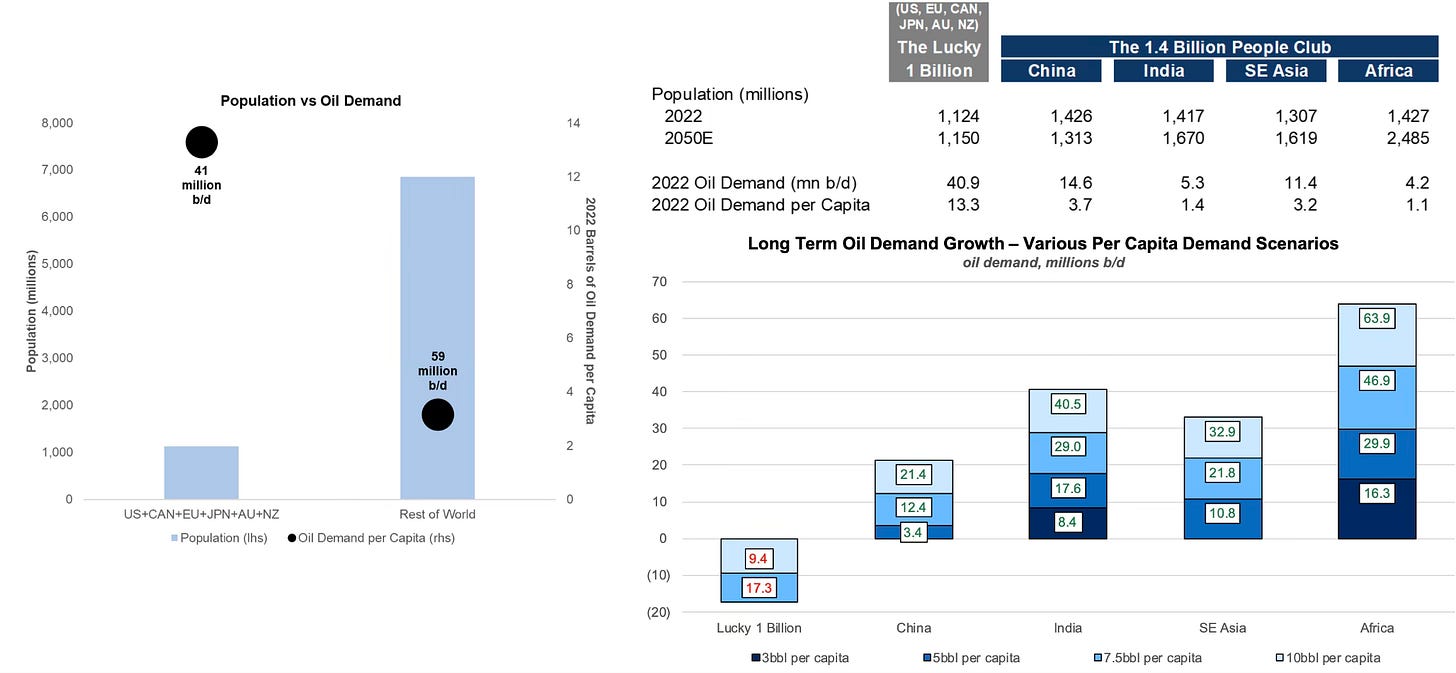

We have consistently described our oil macro framework as "Super Vol" not "Super Cycle," at least for the time being. We agree with those in the super-cycle camp that OPEC spare capacity is generally limited and CAPEX directed at non-OPEC supply is closer to a trough than a peak. As we have noted in our 1.4 Billion People Club series, we also believe there is no clear round-number date when oil demand will peak or plateau (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: We see significant upside risk to long-term oil demand as the Rest of the World moves up the income ladder

Source: EI Statistical Review of World Energy, Our World In Data, Veriten

Rather, our current preference for "Super Vol" has reflected our concern about the near-term economic health of the three largest oil consuming regions—China, Western Europe, and the United States. We have also noted that we have yet to see any evidence that a higher shale oil rig count will not result in higher US crude oil supply. Shale may well be maturing, but it hasn't definitively rolled over, at least not yet, on a structural basis. As such, we have expected that a rise in oil prices to levels north of $100/bbl would lead to a mix of economic weakness and higher shale oil supply.

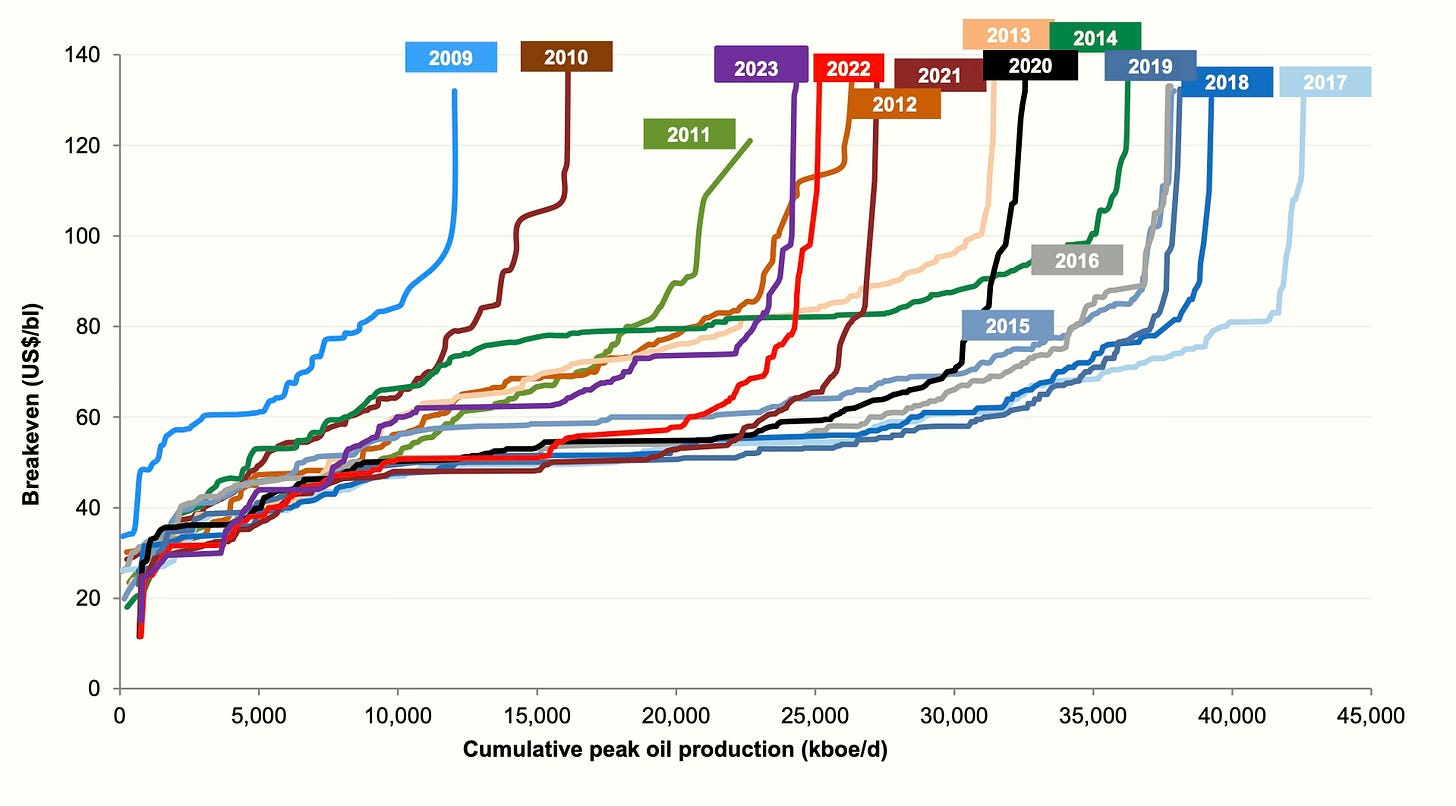

That said, in addition to our constructive long-term oil demand view, we observe that the cost curve for new oil projects has been shrinking and steepening for several years now (Exhibit 2). Moreover, industry and investors for the most part are making little effort to figure out what comes after Tier 1 US shale oil supply. The combination of rising oil demand and a shrinking and steepening cost curve suggest it is just a matter of time before we do move to a super-cycle pricing regime, which for the purposes of this post we will call Super Spike 2.

Exhibit 2: Oil cost curve continues to shrink and steepen in recent years

Source: Goldman Sachs Research

While we are fortunately no longer in the business of public oil price prognostications, we would point out that the last two super-cycles in the 1970s and 2000s led to a 10X and 5X increase in nominal oil prices versus the pre-cycle starting point, respectively. The point of this post is not to provide a framework on how large of an increase in oil prices is possible in the next super cycle. Rather it is to proactively think through the possible ramifications, highlight the top risks, and to think about how corporates and investors can protect themselves from the genius that is our political class.

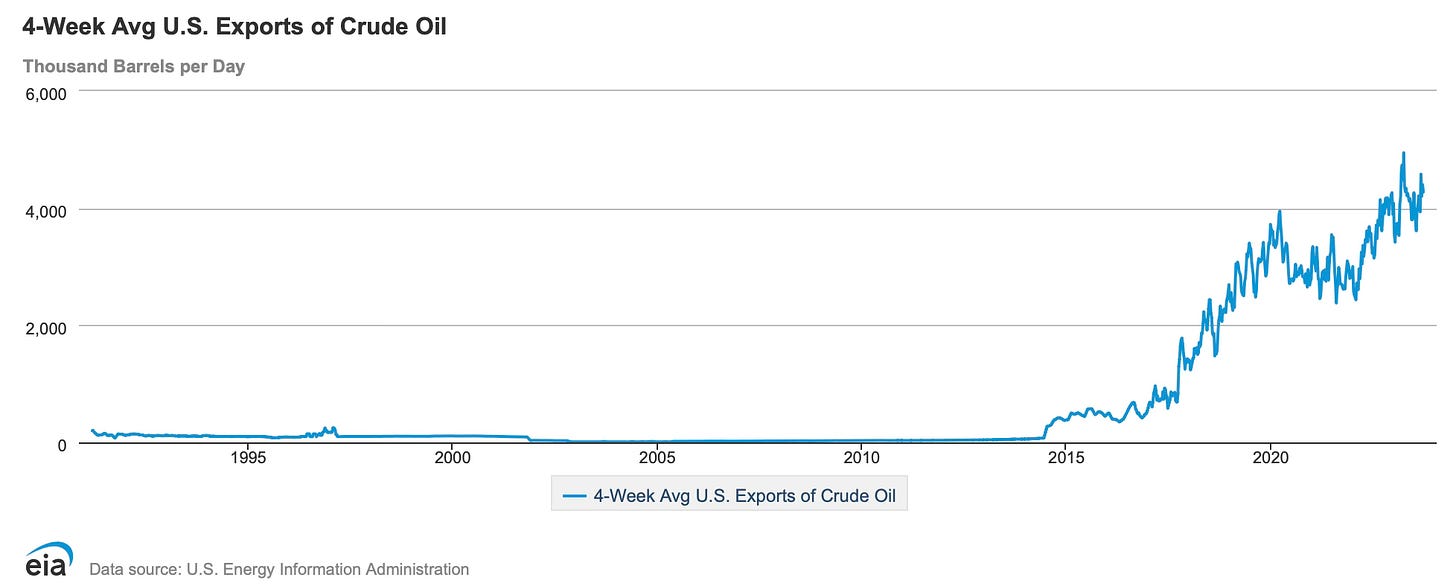

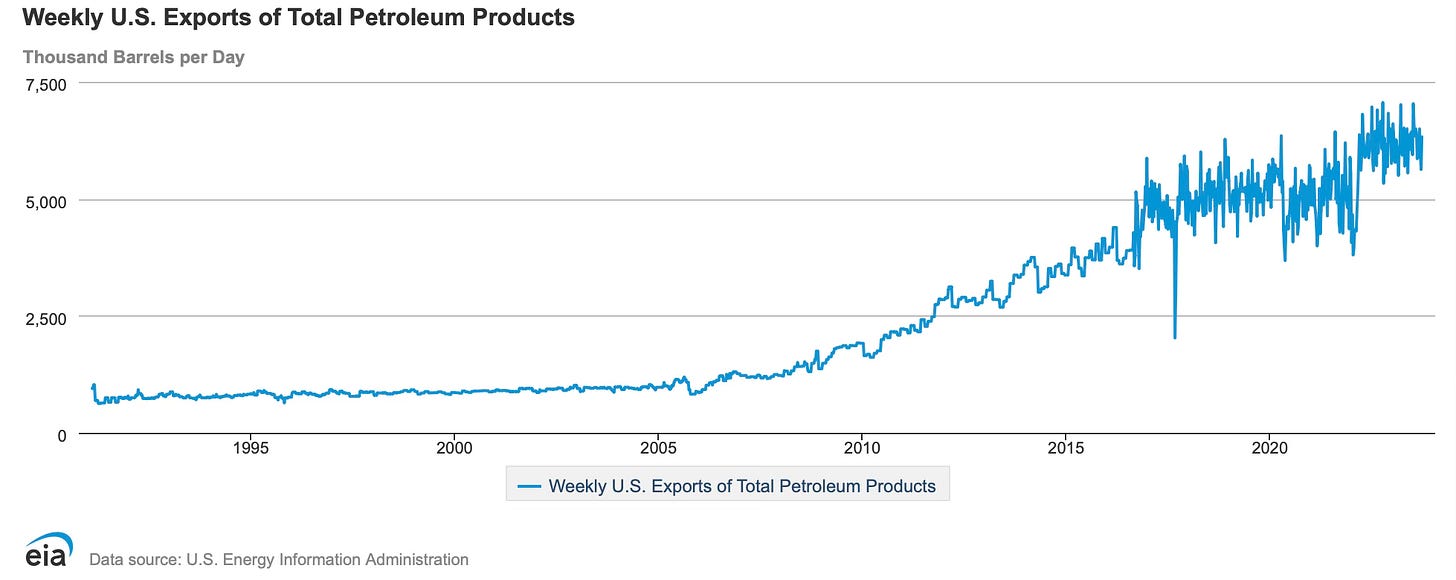

A dominant US shale industry points to different policy risks in a future "Super Spike 2" era

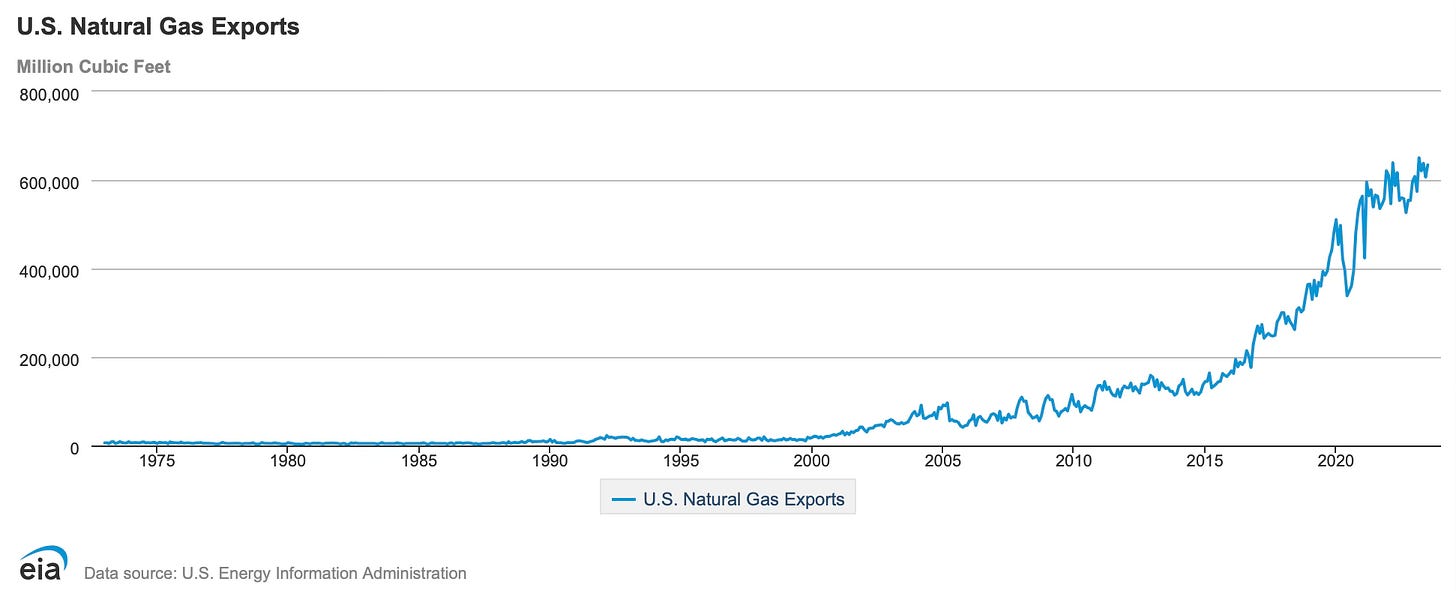

The biggest change from the 2000s cycle is the emergence of a dominant US shale industry and sizable exports of crude oil, refined products, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) (Exhibits 3-5). The number one risk we see in the United States would be future export restrictions on any or all of those fuels. This may not seem likely today, but our concern stems from the fact that the temptation will be high in an environment where oil, refined products, and natural gas prices are well above current levels. We also do not believe this risk is limited to only one of the two major political parties. Anti-globalization and anti-free trade rhetoric now exists in both parties and the mood of whomever is President could have an outsize impact on whether export restrictions materialize.

Exhibit 3: US is now a major crude oil exporter

Source: EIA

Exhibit 4: US is now a major exporter of finished petroleum products

Source: EIA

Exhibit 5: US is now a major natural gas exporter primarily via LNG

Source: EIA

The risk of export restrictions was simply not relevant 20 years ago, in part because the US was a substantial oil importer and did not have any LNG export capacity in the Lower-48 (LNG was exported via the Kenai terminal in Alaska from 1969-2015). Today, even partial export restrictions represent perhaps the most meaningful policy risk facing US shale producers and LNG exporters.

For the USA, we are less concerned about the risk of so-called "windfall profits" taxes, though that concern coupled with other unfavorable fiscal/tax changes is a more meaningful risk in other regions. Fiscal/tax terms around the world tend to become more onerous after significant increases in commodity prices.

Key question for corporates and investors involved in US shale and LNG:

What steps are you taking to mitigate, monitor, or otherwise plan for any future impositions placed on the ability to freely export crude oil, refined products, or LNG? It may not be a near-term concern, but if oil prices were to suddenly double, or more, from current levels, this is a risk worth spending some time pondering.

Does (further) diversification to other regions make sense for your company?

If you are wondering why we have spent so much time just on this risk, it is because it is one that has not mattered historically and was not relevant pre-shale when the US was a significant net importer of crude oil and was not a material exporter of LNG. In our view, the ability to export is taken for granted, certainly by the investment community. Let's hope that remains true. We, unfortunately, do not think it should be taken for granted if Super Spike 2 were to materialize.

GFANZ and the misallocation of capital

As long-time Super-Spiked readers know, we believe the Glasgow Financial Alliance For Net Zero (GFANZ) is a much bigger risk to the health of the traditional energy sector than the more popularly decried trend in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing. More recently, the US Treasury is trying to get into the act of forcing (err, "voluntarily encouraging") financial firms to align lending, capital markets, and insurance activities with some theoretical "Paris-aligned net zero by 2050" pathway. We will have to circle back on what is clearly the original sin with ill-conceived energy & climate policy being pursued in Western Europe, Canada, and by the current US administration and in various so-called "blue" states (note: we recognize this last comment does not seem to be in the spirit of our preferred non-partisan approach; we apologize but it can't be helped in this case. We would note there are plenty of issues with policy prescriptions put forward by US Republicans, but this is not one of those areas).

The idea that financial services firms should be forced to allocate capital on something like an emissions financed metric we believe is about as bad of a policy idea as you are going to find. It certainly moves financial services firms away from their primary objective, which is to earn an acceptable return on equity for investors by providing financing or insurance to businesses, individuals, and governments. Forcing an impossibly fast, non-sensical transition via the overcapitalization of a broad range of companies in the new energies sector is already coming home to roost, as can be seen in the significant underperformance of publicly-traded equities involved with new energies (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Clean energy equities have been under significant selling pressure

Source: Bloomberg

The idea that financial services firms should have been investing even more in these newer areas to "transition faster" has never made much sense to us. Moreover, the attempted starvation of capital and insurance to traditional energy—mind you, primarily to those companies in the western world only—dangerously and unnecessarily seeds control of traditional energy markets to resource producers in the other regions, many of whom are hostile to western interests. GFANZ is a concept that warrants much greater attention, public debate, and vocal pushback.

In our view, there is still way too much attention being placed on ESG investing as the culprit driving the current energy crisis era. No doubt the most recent incarnation of ESG investing needs significant reform. But the biggest policy risk we see is with GFANZ-styled capital and insurance policies that aim to force a skew in lending, investing, and insurance toward new energies and away from traditional energy.

Key question for corporates:

What steps can the traditional energy industry take to ensure robust banking and insurance options exist over the long term?

Does it not make more sense to be proactive at a time when industry is relatively healthy and flush with cash flow than at a future time where the structural cycle may be a headwind?

What steps are individual companies taking to not take for granted banking, capital markets, and insurance access?

New country openings

The exceptional success enjoyed by ExxonMobil and Hess in Guyana is a reminder that new country openings can have a material impact on companies, countries, and investors and can impact global supply/demand balances. Guyana will be a notable component of non-OPEC supply growth for many years to come.

We would divide new country openings into two major buckets: (1) greenfield exploration; (2) brownfield resource development. Guyana is an obvious example of the former. A future re-opening of a country like Venezuela we would put in the latter bucket.

We are far from it today, but in the 1990s development of Venezuela's Orinoco Belt was a major source of growth and profitability for western majors. Remarkably, heavy oil in Venezuela "cold flows" (i.e., without the need to inject steam or energy into the reservoir) several thousand b/d per well. If we are remembering correctly, the heavy oil required local upgrading before usually being shipped for refining at Gulf Coast refineries.

At this time, we do not have a detailed list of countries to watch for in terms of greenfield exploration or brownfield expansion. We would observe that unlike 20 years ago, the list of companies pursuing a mixture of exploration or global expansion is significantly smaller than it once was.

Key questions for corporates and investors:

What non-US shale areas look interesting?

What countries/regions are worth doing work on in case of re-opening (including steps to improve fiscal terms and re-attract foreign investment)?

⚡️On A Personal Note: Visiting New Countries

When my career began in the 1990s, global exploration and resource expansion was a core focus for a large portion of industry. In those days, everyone knew that international E&P was the place to be. The US was mature and unless you wanted to buy the scraps of the Majors (which by the way was a great strategy for Raymond Plank’s Apache and a number of other companies), you needed a global effort, be it exploration, resource development, or both.

My parents did a great job raising my siblings and me. But growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, it was not a time where our family did much by way of global vacations, certainly nothing like what my children have experienced. One of the best parts of being an oil & gas equity research analyst in the 1990s was the opportunity to visit companies and their assets around the world. A few of my most memorable trips from the early days include the following:

Algerian desert with Anadarko Petroleum (circa 1996)

I started covering Anadarko at Petrie Parkman and when I joined JP Morgan Investment Management, it became a top energy holding of ours in the period where Anadarko was discovering oil in Algeria. Paul Taylor, Anadarko’s legendary investor relations head, invited myself, Mike Henzi of State Street, and John Herrlin of Merril Lynch to join him and another Anadarko executive (Bill Sullivan perhaps?) to visit their pre-start-up operations in the Sahara.

What an experience it was staying at the workers camp, though I wasn’t a huge fan of goat stew (or was it lamb?) served for dinner that night. We took a low flying prop plane to tour their well sites; the French speaking pilot could tell I wasn’t faring well with the twists and turns…but I held it together and I still remember the big hug he gave me when we returned to base for not throwing up during the flight (I was seated next to him). Still, a turbulent plane ride beat the AK-47s (or equivalent) we faced by the seemingly teenage “guards” in the middle of the desert demanding we show our Desert Passes. Algeria was the first time I’d been in a car where they checked underneath for potential bombs.

The trip reinforced my view of the significant upside potential Anadarko had in Algeria and the value-creation potential from an impact exploration program. Anadarko was a good call for me at JPMIM, at least as I remember it all these years later.

Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore with Shell (1998)

Shell hosted an analyst trip through the Far East in 1998. It was always amazing to visit the foreign operations of the Major Oils and witness the consistency of each company’s corporate culture around the world. I don’t recall the specific senior Shell executive who was with us, but it was in the glory days of Cor Herkströter Maarten van den Berg, Malcom Brinded, and Linda Cook.

Shell was then, and frankly still is, an exceptionally great company. I recall it in those days being more decentralized, in contrast to the centrally-controlled Exxon; there was no “God Pod” at Shell. You had The Hague (center) and the various major countries they operated in around the world. Still, the very different approaches worked for each company when you look at the spectacular results over a century for both Shell and Exxon (1910-2010).

On this trip, it was my first experience with forest fire smoke. No climate crisis in those days; rather, I believe that came from the seasonal acreage burning season in Indonesia. Shell had just built a new refinery in Thailand, Map Ta Phut that we visited. That evening, we experienced Bangkok night life, something that was definitely better to have done pre-spouse, pre-family (to my kids, nothing to see here). Kuala Lumpur is where I learned that the relationship between Major Oils and host countries was unique; minimum return thresholds were especially welcomed in a year oil prices briefly fell below $10/bbl during the Asia Financial Crisis.

Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan with Credit Suisse (1998-ish).

Growing up in the USA during the peak of Cold War, it would not have been possible to have imagined that someday I would take a business trip to a place that was no longer called the Soviet Union. In those days, all three of these countries were still trying to recover from the Soviet collapse and it was a classic “new country” opening for known resources.

There must have been 25-30 of us (all buy-siders plus our CS hosts) on a chartered plane we were told was previously in the service of Eduard Shevardnadze, who we knew as Mikhail Gorbachev’s Foreign Minister at the end of the Soviet Union and went on to become the president of Georgia, a former Soviet state. On our arrival to Moscow, we were assigned a driver to take us to visit some of the tourist sites. But I remember at the first stop, as I was about to get out of the car, the driver pulled his gun out, looked around, and then opened the door for me. I didn’t think any site was worth seeing if it somehow involved the driver feeling the need to brandish his weapon.

The oddest part of the trip was when our plane landed unexpectedly in a never-explained state or country. The pilots said they had to “confirm their papers” and were gone for about 4 hours as I recall. The flight attendants did their best to keep the drinks flowing. Ultimately, the pilots did return; no real explanation was ever offered for that stop. We were glad they came back and our trip continued. Baku was easily my favorite stop, a historic and beautiful city.

There was something about that trip that was very different than visiting Southeast Asia, where the partnership between the companies and the countries was front and center. This was an analyst-hosted trip to be sure. But the FSU was going to have a different approach to dealing with foreign companies, especially those from the USA, than was the case in Asia or for that matter Africa.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Very good analysis, Arjun. I work in Midland for a small independent (as I have commented before), and the trends I see for the shales:

1) Rig counts are not going to increase substantially for the reasons you note, but also because the larger players are consolidating leasehold to drill longer laterals (the standard is now 3-milers). Thus, the acreage can be developed with the same or fewer rigs.

2) consolidation will continue as the larger E&Ps with cash will buy out others (XOM & PXD for example)

3) The effects of pressure depletion will become more pronounced as more crude is produced. Namely, Gas-oil ratios (GORs) will continue to rise as reservoir pressures drop below bubble point. I am already seeing this in newer completions where initial production rates are very high, but oil declines are much steeper over the first year than previously as gas production increases or stays higher longer. Gas takeaways out here will continue to be constrained, and we will probably over-build the pipelines just as gas, too, starts to decline dramatically.

4) As bottom-hole pressures decline, operators will face more problems with paraffin and scale build-up, especially in the Spraberry wells. This will increase operating expenses as more chemical treatments and well interventions (workovers) are needed.

I can think of more, but these are the big ones that the US shale industry will face over the next ten years.

Great pointing out the policy risks and cannot look to the past (no risk because little exported). The risk of future policy wanting to limit exports of “our oil and gas is worth thinking about. But a longish comment on tier 1 vs 2 shale. There is group think that this is a big deal. I disagree. The industry has gotten better extracting from shale. A decade ago no one believed the Haynesville could be economical at $3 gas. In the Permian, there is So Much room for improvement of oil extraction per block of rock (which is different from rate per well--which is a poor metric because it is easy to game). With application of some science and some engineering, what is now considered to be tier 2 rock can definitely produce more oil per block than has been produced from tier 1 rock. A point. There is, as has happened off and on in the past, enthusiasm for re-fracturing as an economic positive. Re-fracturing is really proof that you screwed up the first time. This is analogous to manufacturing cars. Toyota taught the industry (and over time kicked Detroit’s ass) that it is better to spend the money up front on proper design and manufacturing than to remanufacture and recall. where re-fracturing makes sense today, it should be looked at as a big failure of the past. Maybe technology moved and that’s the reason for the failure, but I see today almost no companies really applying continuous improvement technologies. Or spends modest amounts on really understanding the subsurface (like building airplane wings without spend on testing the metallurgy-it’s crazy). While running a manufacturing company i implemented Toyota processes so speak from experience. Having this be C Suite word salad is worse than a waste of time. It has to become institutional DNA.

A final story. Ford had a group from Toyota tour Dearborn after Ford (thought they) had put in great quality systems. Like their Quality is Job One campaign, for which they had big banners strung around the factory. Obviously proud of this campaign, they asked their Japanese guests what they thought. The reply. “Why do you need signs to tell people this? “. The point being, if you have to put it on a banner, it isn’t in your workers’ DNA, so it will not succeed. I can assure you. Continuous improvement is not in our industry’s DNA at anywhere near the level of Toyota et al. If it had been for the past decade, then we would likely be extracting +50% more oil from each block of unconventional rock.