We follow up on our look at recent Super Major M&A activity (here) with thoughts on what has been a steady flow of transactions in the E&P space, highlighted most recently by transformational mergers between Diamondback Energy and privately-owned Endeavor as well as Chesapeake Energy with Southwestern Energy.

In this post we examine five questions regarding overall E&P M&A activity:

Is the post-merger company simply bigger or is it also better?

Is a particular deal representative of the post-merger company being "on offense" or "defense"?

How do we think about the return on capital employed (ROCE) implications of E&P M&A activity for the post-merger entity?

What are the common pitfalls of E&P M&A activity?

Are investors always better off when an acquisition target accepts a takeover premium?

We will interject a few disclaimers at this point. At Super-Spiked and at Veriten we do not provide public, company-specific corporate or investment advice. Nothing in here should be construed as such. There is no one-size-fits-all M&A advice or perspective, as what might make sense for one company might not for another, even if transacted on the same terms. At Veriten, our team has a range of backgrounds and perspectives on this topic and many others; some of that nuance is reflected in Super-Spiked, but some may not be. Veriten either does or may seek to do business with companies mentioned in this post.

Is the post-merger company simply bigger or is it also better?

What does "better" mean?

The new company can generate double-digit, write-offs-adjusted ROCE (defined in subsequent section) on a go-forward basis for a greater number of years than it was able to pre-merger, what we have called "extending the runway" of advantaged profitability generation.

The new company will be able to outperform the ups and downs of commodity prices, which we believe is consistent with generating double-digit ROCE over a full cycle.

The new company is better positioned for sustained growth, future M&A, capital returns to shareholders or all of the above. This would also mean it is better positioned to emerge as a going concern capable of perpetuating double-digit ROCE over the long run or will have enhanced attractiveness as a future take-out or merger-of-equals candidate.

The balance sheet and overall financial position of the new company can better withstand and potentially take advantage of commodity price downturns.

The new company can attract a broader range of shareholders, including becoming a more important component of key indices like the S&P 500.

What does "not better" (also known as "worse-off") look like?

Conflating size with improved underlying performance.

Not being prepared for the risk that a commodity downturn can happen at any time and without warning.

Acquiring a previously in-vogue area as it is nearing (or past) peak performance.

Buying lower-quality acreage or assets at a price that implies it is premium acreage. To be clear, we do not object to buying so-called "Tier 2" acreage, so long as it is done purposefully and with transparency.

Having an incompatible cultural fit, something that can be difficult for investors to gauge. The post-merger management team should not look like a “Greatest Hits” compilation where Company A gets 1 executive and Company B gets 1 and then A gets another 1 and B gets another 1. Pick the best team that is most likely to work well together; often, one side has to "win" though undoubtedly an infusion of fresh perspectives from the other company can be invigorating to an enterprise.

Investing in new areas without clear expertise in that area. It is possible such expertise could come from the acquired entity, making cultural fit, retention, and integration plans especially important.

Is a particular deal representative of the post-merger company being "on offense" or "defense"?

We are going to slightly stray from our preference to not discuss contemporary companies by highlighting two recent, high-profile deals: Chesapeake Energy (CHK)-Southwestern Energy (SWN) and Diamondback Energy (FANG)-Endeavor Energy Resources (private). At a time when much of the traditional energy industry is still struggling to articulate positive, forward-looking equity stories, we credit the management teams of Chesapeake and Diamondback for bold moves that we think position their respective companies well for the future. Neither transaction is without risk; how could they be if one is to move the needle forward?

What we like about both transactions:

The acquiring companies have demonstrated knowledge and expertise with the acquired assets.

Both companies reach a market capitalization that is of increased relevance to investors in their respective areas of focus. CHK-SWN will become a premier large-capitalization, diversified (basin) US natural gas producer. FANG will become the pre-eminent, high-quality, large-cap, pure-play Permian producer.

Both companies are set up well to engage in opportunistic M&A in coming years, with neither facing pressure to "have to do something" to add inventory, at least not over the next several years.

We consider both deals as being boldly "on offense," with the future Chesapeake-Southwestern and Diamondback-Endeavor being clear leaders in their respective areas.

We believe prudent capital allocation at both companies can allow for a combination of competitive ROCE and competitive shareholder distributions to be generated over the long run.

While few transactions are purely "offensive" or "defensive," what we like about both of these deals is we believe the post-M&A companies are clearly better than before and are well positioned to figure out what comes next from a position of strength. The nature of upstream resource depletion, changing cost curves, and commodity price volatility means no company can stand still. And there is no such thing as a risk-free deal.

To further clarify the "on offense" versus "on defense" descriptor, we would observe that there are many deals that do not really move the needle for an acquiring company in terms of improving relative or absolute positioning or with any of the key metrics we care about. This is not simply a size comment, as there are many "tuck-in" deals that make lots of sense for the purchaser. It is really about whether a transaction is transformational in nature or sets up the opportunity for the next big step forward. We see CHK-SWN and FANG-Endeavor as favorably transformational for the respective companies.

How do we think about the ROCE implications of E&P M&A activity for the post-merger entity?

As even casual readers of Super-Spiked will undoubtedly recognize, we are strong proponents of focusing on corporate-level profitability metrics, with our favorite being ROCE. At the sector level, we are comfortable using reported earnings and balance sheet metrics, which we think is appropriate for the longer-term analyses we feature. However, there are many important caveats to how we think about ROCE that sometimes get mis-interpreted in company-specific analysis:

The framework and philosophy of our profitability/ROCE framework should not be confused with a religious adherence to a mechanical calculation.

All profitability metrics have pros and cons, good applications and bad interpretations, and all can be manipulated or misunderstood—intentionally or via accounting rules—such that it becomes less meaningful.

At the company specific level, near-term ROCE can be artificially boosted by recent write-offs. It makes sense to adjust for those write-offs by boosting DD&A and reducing earnings in the numerator and adding back the amount of the write-off to the denominator, which will provide a truer sense of profitability for individual companies. This is what we mean by write-offs-adjusted ROCE.

When companies issue stock in M&A transactions, we believe the interpretation of go-forward ROCE is not as straightforward as simply doing the mechanical calculation for the post-merger entity.

This entire topic is deserving of its own post and we still plan to follow up on our recent ROCE framework deep dive (here). On the last bullet above about M&A-impacted ROCE, here are some perspectives on the challenges that we see with the calculation with stock-for-stock deals. We recognize not everyone will agree with our views.

The accounting treatment of all stock, all cash, and mixed cash/stock deals are identical in terms of the denominator in ROCE. Our suggested improvement would be to move to a "pooling"-adjusted basis (a former accounting treatment no longer used) for the portion of the deal where shares are used. If a company is issuing its premium price-to-book value stock, it has never made sense to us that ROCE penalizes a company for the gross amount of the acquired company's book value write-up without consideration of the premium of the issuing shares. Share-for-share issuance is almost always about relative, not absolute, valuation.

In a deal where a fixed ratio of shares is issued (most deals today that involve stock), the subsequent gain or loss on the acquired company’s shares post the announcement (or media leak) until closing either hurts (if the stock price increases) or helps (if the share price declines) the ROCE calculation, which is counter to the investor or market reaction. Using a recent example, investors reacted very favorably to Diamondback's purchase of Endeavor. It's future ROCE, all else equal, will be slightly impaired by this favorable reaction. That does not seem right from a future profitability interpretation perspective.

It is possible for companies to make great deals that are dilutive to ROCE in the near term but value-added over the long run. At the same time, we recognize there are plenty of deals where the promised long-term accretion does not materialize, so please don't consider this to be a blanket get-of-jail-free card.

What are the common pitfalls of E&P M&A activity?

The biggest risks we see with E&P M&A activity from the perspective of the acquiring company:

Management does not fully understand the asset base it has purchased and disappoints on some combination of acreage productivity, ultimate resource, capital spending, and costs.

A corollary to the first point is to understand where we are in the life cycle of a play or basin and whether an acquisition is happening early, in the middle, or toward the end of its natural life, at least as it relates to the current phase of development projects.

Post deal balance sheet health is impaired and a company is not prepared for an unexpected downturn.

Instead of retaining the best employees of the merged entity, the better people opt out and employee quality and effectiveness deteriorates.

"Greatest hits" post-merger management teams.

A lack of cultural fit, especially in a merger of equals or where the employees of the acquired company are needed.

Deals that occur in the later stages of a long-term commodity up-cycle.

On that last point, it remains our view that we are in year three of what we believe will be a decade-plus period of improved sector profitability albeit with a "Super Vol" rather than super-cycle commodity macro backdrop. Therefore, we are at a time where the odds of having good deals are higher, all else equal, than will likely be the case 5-7 years from now.

Aside from the usual "they don't understand the assets they are acquiring" risk that always exists, we are most worried about whether merged companies are adequately prepared for the inevitable 12-month period of below normal commodity prices. For oil, that would mean a fall to $50/bbl (or lower) for WTI and for Henry Hub natural gas we are living in real time the fall below $2/MMBtu. There is nothing about the macro backdrop that implies "smoothness" should be assumed even if WTI (and Brent) oil prices, US refining margins, and global natural gas prices turn out to be decent on average over the next decade. Given a sizable natural gas resource base in North America, it is less obvious to us that the average Henry Hub natural gas price will be as favorable as the other areas mentioned.

Are investors always better off when an acquisition target accepts a premium bid?

In our view, the answer to this question is a clear "no" in the event that it is early in the long-term up-cycle and the target company has a strategy that will deliver superior stand-alone shareholder returns than the acquirer, taking into account the near-term certainty offered by the takeout premium and overall characteristics of the offer (cash versus shares, etc.). We offer two contrasting examples from the Super-Spike era: XTO Energy and Occidental Petroleum.

XTO Energy

XTO Energy was a 2000s-era Street favorite and nailed the "stay independent" versus "now is the time to sell" decision. To be clear, we have no knowledge that XTO was ever approached prior to accepting ExxonMobil's offer, so we discuss this merely as a hypothetical. In our view, shareholders were fortunate that XTO stayed independent during the 2000s and added shale acreage at a time when few knew that much about the game-changing potential of US shale. Staying independent through the 2000s and then selling to ExxonMobil in 2009 at a time of advanced maturity for both the super-cycle and its acreage is about as near perfect long-term cycle timing as we have seen in our 32 year career (Exhibit 1).

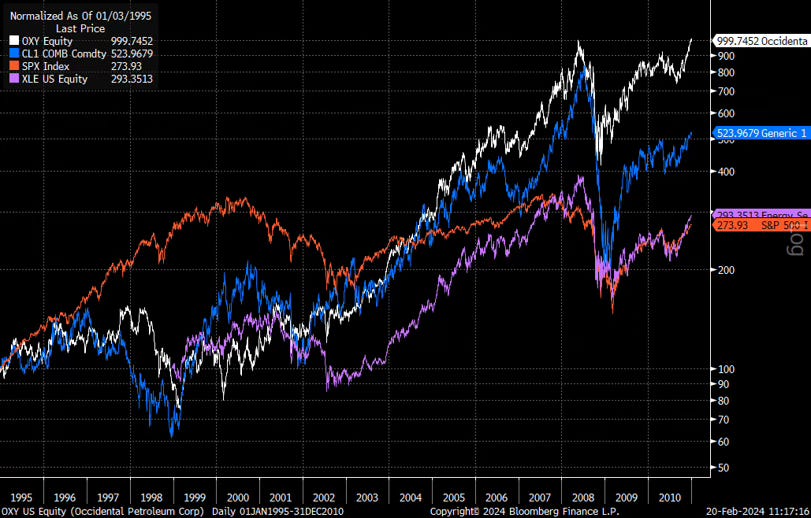

Exhibit 1: XTO shares massively outperformed oil prices (CL1), the energy sector (XLE), and the S&P 500 (SPX) during the 2000s

Source: Bloomberg

Occidental Petroleum

A contrasting example is Occidental Petroleum (OXY), which significantly underperformed in the 1990s, was broadly disliked by the Street (in the 1990s) but engaged in what turned out to be massively transformational M&A via the acquisitions of Elk Hills (California) and Altura (Permian Basin). It all turned out great for OXY shareholders when the 2000s super-cycle kicked in (Exhibit 2).

Similar to XTO, we have no knowledge that OXY was ever approached during the time it was struggling. However, if literally any larger company had offered a 30% cash premium during the late 1990s or early 2000s, there is not a Street analyst who would have called for OXY to stay independent in anticipation of the upcoming super-cycle and transformational deals. And to be clear, yours truly would have been firmly with consensus, as we wrote about in our Dumb Calls I Made As A Street Analyst post (here).

Exhibit 2: OXY shares struggled in 1990s before taking off in the 2000s

Source: Bloomberg

Companies that should “go” and take the premium

In contrast to 2000s-era XTO and OXY, there are traditional energy companies that should have taken or should seek an acquisition premium as evidenced by structural underperformance. In the interest of politeness, we will refrain from naming names. Most Super-Spiked readers are capable of pulling up tickers, running long-term total return screens over various time periods, and examining historic and expected profitability.

⚡️On A Personal Note: Apple Vision Pro

With the so-called "Magnificent 7" stock market leaders sucking the fund-flow-life out of the other 493 stocks in the S&P 500, we are going to take a break from energy & climate debates, career history, life lessons, and all such things to talk about Apple's newest product: Apple Vision Pro. In my view, this is the most exciting new product from Apple since its launch of the iPhone. I expect it to be life changing and the future of personal computing.

To be clear, I am not planning on buying this first generation device. I waited for the iPhone 4 to get my first non-dumb phone. Undoubtedly the weight and form factor will favorably evolve for Vision Pro in future years.

There are three use cases I am most looking forward to:

Giant MacBook Pro screen when traveling. I don't like Excel on the small screen; I need a big screen for modeling. Based on various on-line reviews, it sounds like this is possible today (i.e., super-sized laptop screen projection), but may not be sufficiently mature yet to warrant purchasing this initial Vision Pro.

The opportunity to see Led Zeppelin at Madison Square Garden during their mid-1970s peak. I was too young to have caught them live. I believe future iterations of Vision Pro and its app infrastructure will enable the recreation of an immersive experience that will be the next best thing to having actually seen Zeppelin in person during their hay day. I want to “go” to the actual concert, not watch a replay on a flat TV screen.

Knicks courtside! The potential for home viewing of sporting events is likely to be transformed with future iterations of Vision Pro and evolution in broadcast rights packages. Going to games in person has its downsides, especially in the New York City area, and is certainly not possible on a regular basis. I can't wait to buy the Knicks Vision Pro Courtside Seat package, where I'll be able to watch the game from my own coach but with the feeling of actually being courtside. Given the Knicks challenging performance history, hopefully Apple can get the technology progressed while Jalen Brunson is still near his prime.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue

Arjun, Just received the Goehring and Rosencwajg report in which they further discuss the Norwegian EV situation under the heading "The Norwegian illusion." Don’t know how to attach it to this comment. The other illusion or vision I have is you sitting in your coach ( circa 1900) watching the Knicks. We have come long way since then. Appreciate your substack immensely.

Since it’s a Saturday, i want to pick up on your non oil and gas commentary about the Apple Pro. It does indeed look cool but that price tag is a big barrier. Check out Zuckerberg personal

Compare and contrast of the Apple v Meta product. Meta is a fraction of the cost.