Where Are We in the Energy Cycle, A Framework (Spoiler: It's Early Days)

Navigating the Energy Crisis Era

The overwhelming question asked whenever energy equities rally is: Are we at peak? It really doesn't matter which type of cycle we are in—structural bear, structural bull, or anything in between. Every time energy rallies, there seems to be a pervasive fear that it's as good as it is going to get and that the end is near. This is true among both sector specialists and generalist portfolio managers. Energy is not like tech where investors get super excited to buy and hold companies of all capitalizations.

To be sure, the energy sector has always been volatile in a way you don't see with most non-commodity sectors. It is in fact that fear of volatility that often creates the compelling opportunities to invest if—and it's a big if—we are early in a structural ROCE upcycle. This is where I think we are today, driven by normal supply/demand/capital cycle factors and now turbo-charged by the messy energy transition quagmire and resulting energy policy nightmare we find the world in. It is the basis of Super-Spiked’s creation.

A few key conclusions from the perspective of when structural ROCE upcycles end:

CAPEX: Structural Energy upcycles end AFTER, not before, a multi-year, major increase in CAPEX. Currently we are still closer to the trough of the CAPEX cycle.

REINVESTMENT RATES: Structural Energy upcycles end when industry-wide reinvestment rates are closer to 100%, not at or near all-time lows as is currently the case.

ROCE: Structural Energy upcycles show signs of stress when ROCE begins to underperform a given level of commodity prices. This one admittedly is trickier to gauge as year-to-year ROCE can be volatile driven by short-term oil price movements. Rather, I am focused on the longer-term ROCE trend and looking for the second derivative turn for the worse where the increase in capital intensity (from higher CAPEX and reinvestment rates) starts to negatively impact structural ROCE, especially versus underlying oil price trends (e.g., ROCE falls versus flat or rising oil prices). Currently, CAPEX and reinvestment rates are closer to all-time lows rather than all-time highs. As such, I believe the risk of ROCE underperformance is low at the sector level; company specific risks always exist.

S&P 500 WEIGHT: Structural Energy upcycles typically end when Energy’s S&P weighting is in the low-to-mid teens. Currently, Energy has merely rallied to just over 5% of the S&P 500 from its 2% October 2020 low. While a lot depends on the outlook for other sectors, energy tends to "punch its earnings weight" in the S&P 500 arguing for a 10%+ S&P market cap weighting today.

RUSSEL GROWTH WEIGHT: Structural Energy upcycles end when Energy’s Russell Growth weight is noticeable, which I might characterize as over 10%. Currently, energy is just 2% of Russell Growth, up modestly from the circa 1% it was for much of the 2016-2021 period. To be clear, traditional energy is not a growth sector. Still, during the up portion of the structural cycle, it has historically reached a 10%+ weighting in the Russell Growth Index.

It's all about the capital cycle, which drives the ROCE cycle

At the end of the day, the overwhelmingly driver of cycle position for capital intensive commodity businesses like traditional oil & gas is, unsurprisingly, the capital spending cycle. It is capital spending that drives returns on capital employed (ROCE). To simplify, capital spending on projects at the low end of the future cost curve will generate favorable absolute and relative (to the sector) ROCE. Given oil and gas fields all have a finite life and exhibit natural depletion (i.e., decline in productive capacity), there is a constant need to invest capital to generate ROCE.

That last point is often mis-understood and mis-applied by investors and managements—almost always in the opposite directions. Investors would typically prefer a “zero” CAPEX world (give me back all the money!!!) whereas managements are regularly too optimistic on the expected profitability from capital projects and M&A. Somewhere between zero and max CAPEX lies the sweet spot of an optimized ROCE and growth outcome.

Exhibit 1: Energy sector ROCE cycles are long-term in nature

I have shown Exhibit 1 many times before. The key messages are now well known:

There is nothing more important to the success or failure of traditional energy companies than understanding capital allocation.

Return on capital cycles are long-term in nature: 10-15 years up and 10-15 years down

The ROCE cycle is not 1:1 with the oil price cycle as capital intensity, operating and capital cost inflation/deflation, fiscal regime, and inherent geology all change over time.

The ability to generate earnings and cash flow comes from capital spending and M&A activity.

Over multi-decade time frames, I would expect the average return on capital for the sector to approximate its cost of capital to ensure sufficient supply growth to match demand growth.

Within that framework, the top two ROCE quartile sectors have historically generated multi-decade ROCE (bull and bear markets) in the double-digits and in excess of cost of capital. The opposite is true for the bottom two ROCE quartiles.

The point of this post is not to give another long lecture about the importance of profitability (i.e., ROCE). But rather to analyze where we are in the capital cycle to assess whether energy equities are closer to trough, mid-cycle, or peak. In my view, we are still much closer to the start of this new cycle as capital spending is barely off its 2020 lows and well below the kind of levels that are commensurate with meeting, let alone exceeding, expected oil and natural gas demand for the coming decade.

CAPEX: We are closer to trough than mid-cycle or peak

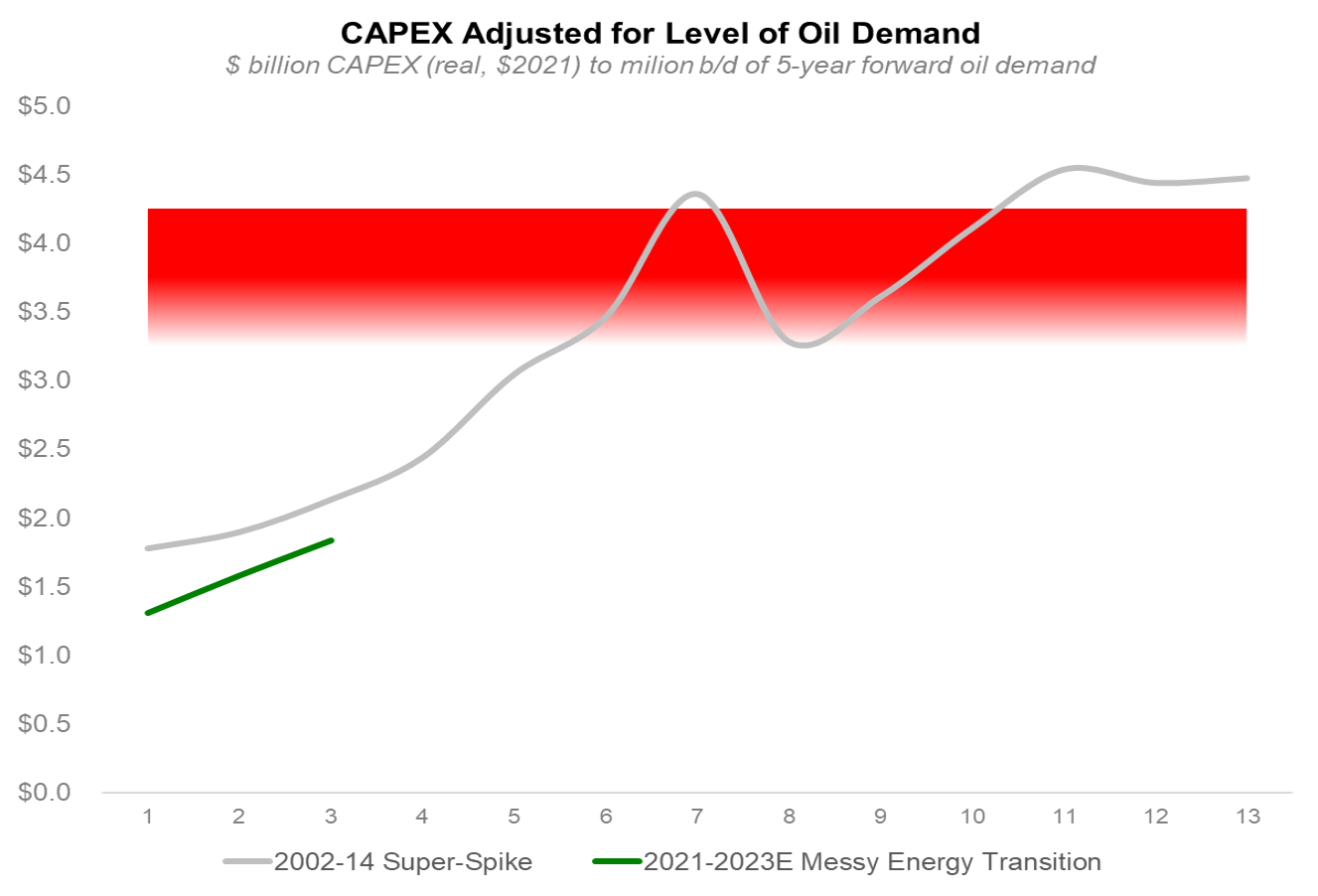

Exhibit 2 looks at capital spending for the universe of publicly-traded traditional energy companies I include in my ROCE work. It is a comparison of how the current Messy Energy Transition era compares to the Super-Spike period of 2002-2014. To read the graph, on the x-axis Year 1 for the Super-Spike era is 2002 and for the Messy Energy Transition era is 2021. The red shaded area shows the potential “danger zone” for industry CAPEX, where we might start to wonder about the remaining duration of the structural energy bull market.

Exhibit 2: CAPEX for publicly-traded traditional energy companies

Key points:

In absolute terms using real $2021, capital spending is tracking similarly to the Super-Spike era both in absolute amounts and rate of change.

I believe the perception that capital spending has been slow to respond to higher oil and natural gas prices is not accurate—the reaction looks similar to the prior super cycle. Note: for 2022E, I use the first nine months of actual CAPEX and an assumption that 4Q CAPEX will match 3Q. For 2023, I have used a 25% increase in CAPEX as my initial order-of-magnitude estimate.

Absolute CAPEX levels are well below what I am calling the danger zone of $300-$400 billion (real $2021) for this universe of companies.

Exhibit 3 adjusts the CAPEX data shown in Exhibit 2 for the level of 5-year forward oil demand. As an example, the 2002 data point divides 2002 CAPEX ($ billion, 2021 real) by average oil demand from 2002-2006.

Exhibit 3: CAPEX adjusted for the level of oil demand

Key points:

The point is to recognize that the absolute level of CAPEX will be driven by the outlook for oil demand and that CAPEX across time needs to be sized correctly not just for inflation but also for the level of demand.

I am using ex-post figures to keep things simple. I do not believe a reconstructed ex-ante analysis would change the picture or key conclusions.

On a demand-adjusted basis, CAPEX is trailing the 2002-2014 period, given absolute CAPEX is similar despite 25% higher oil demand.

Let that sink in for a moment: Over the last 20 years, oil demand is UP by circa 25%. Yet, somehow, through magical thinking and make-believe policies and “technology”, many seem to think oil demand is nearing peak before entering terminal decline. Good luck with that view.

The slope of the demand-adjusted CAPEX line looks similar to the stand alone CAPEX figures, with the point being that companies seem to be reacting similar to the prior era in bringing back CAPEX as noted in the previous section as well.

Similar to the absolute data shown in the Exhibit 2, CAPEX relative to the level of oil demand is well below “danger zone” levels.

Current CAPEX would be consistent with a 67% decline in future oil demand. To be clear, I don’t believe oil executives are forecasting that level of demand hit nor do I expect there to be any chance demand could fall by that amount by 2030, 2040, or 2050, even if it does happen to be consistent with the “net zero by 2050” scenario in the IEA’s similarly titled report. I make this point merely to illustrate there is significant room for CAPEX to increase before we need to worry about over-optimism (again, from an industry perspective; that point will vary for individual companies).

REINVESTMENT RATES: We are basically at the all-time low

The biggest difference with the Super-Spike era is sharply lower reinvestment rates as shown in Exhibit 4. It is likely the much lower reinvestment rates that is creating the perception industry has been slower to respond to better oil prices this go round. Reinvestment rates measure CAPEX relative to cash flow from operations (i.e., the percentage of a company's cash flow that is being reinvested).

Exhibit 4: Reinvestment rates for publicly-traded traditional energy companies

Key points:

Remember, this is an industry wide metric and the major integrated and international oils have consistently generated free cash flow from operations (defined as cash flow from operations less CAPEX but before dividends and other capital returns to shareholders).

While E&P companies traditionally reinvested 90%-130% of cash flows, historically industry capital spending has been dominated by the major integrated and international oils.

In contrast to the absolute or demand-adjusted CAPEX figures shown in Exhibits 2 and 3, reinvestment rates are noticeably lower versus prior cycles.

Notably, reinvestment rates tend to dip early in a new upturn as cash flows ramp ahead of CAPEX. This cycle, the reinvestment rate dip actually looks to be slightly shallower than the 2002-2014 cycle even as absolute reinvestment rates are appreciably lower.

Structurally lower reinvestment rates are probably the most compelling evidence that structural ROCE improvements are on-track to continue for the foreseeable future.

This may be the single most important "leading" metric to watch to gauge when the ROCE may turn down (i.e., ROCE underperforms relative to oil prices)

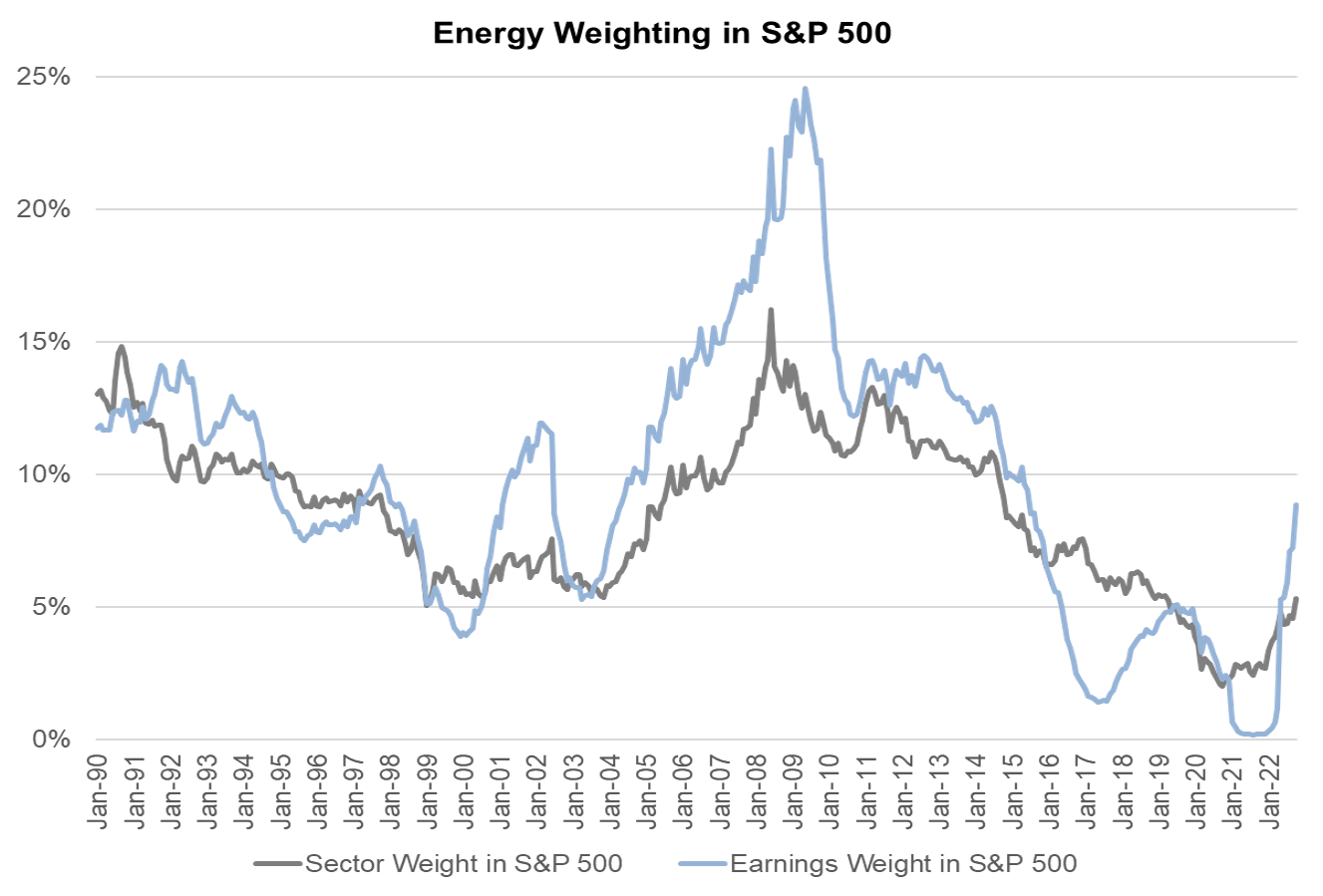

S&P 500 WEIGHT: Energy under-punching its earnings weight by 50%

Exhibit 5 highlights a point I have previously made that the Energy sector tends to "punch its earnings weight" in the S&P 500 (borrowing a phrase from my friend and former colleague David Kostin). Currently, Energy is just over 5% of the S&P 500 on market capitalization despite an earnings weighting that is on-track to exceed 10% in the coming year.

Exhibit 5: Energy earnings and market capitalization weighting in the S&P 500

RUSSEL GROWTH WEIGHT: Still at trough

Traditional energy is not a growth sector. It is a value sector. That said, as shown in Exhibit 6 at cycle peaks it tends to get a notable weighting in the Russell Growth Index. Currently Energy is just 2% of Russell Growth, well below its 2012 peak of 12%.

Exhibit 6: Energy weighting in Russell Growth index

Growth vs Value and Energy vs Tech

Both Growth versus Value (Exhibit 7) and Energy versus Tech (Exhibit 8) are deeply cyclical as I have previously noted. In both cases, we are barely off of trough and well below historic peaks.

Exhibit 7: Russell Growth relative to Russel Value

Exhibit 8: S&P Energy sector relative to S&P Tech sector

Implications for executives of traditional energy companies: Spend better, please

Key suggestions:

I am going to start off with an apology to all of my former institutional investor clients: industry CAPEX is unsustainably low and needs to increase (an apology is required since my comment would appear to give license to executives that more spending is OK). Without adequate oil and gas supply, economic and environmental health suffers.

There is no message here that unbridled spending and aggressive growth targets should resume. Rather, what are the opportunities of competitive advantage for your company to extend the duration of advantaged returns? How do you protect your balance sheet? How do you incorporate a Super Vol mindset?

For companies, it is imperative to look back at the Super-Spike era and other prior periods to understand the capital spending cycle—both at the macro and individual company level—and how it evolves from reasonable (i.e. improving underlying profitability) to unreasonable (worsening underlying profitability).

While I don’t think the second (i.e., worsening) stage can be entirely avoided in deeply cyclical, capital intensive commodity business, the ill affects can be minimized and S&P 500 competitive performance is possible as we saw with the larger integrated oils during the 1990s.

The overarching micro consideration is to understand how does your historic corporate-level profitability compare to what you anticipated, adjusting for oil and gas price changes? We know industry profitability was really poor over 2010-2020 despite oil prices being within forecasted ranges. Why was that the case at your company?

Implications for policy makers: Gross zero energy poverty, while minimizing negative externalities

Key suggestions:

Everyone on Earth wants available, reliable, and affordable energy. Policies that support more energy are good. Policies that aim to restrict or deny energy availability, affordability, and reliability are bad and doomed to fail.

We need more energy sector capital spending. In all sectors. Today. Tomorrow. And the next day. And the day after the next day. Probably for another decade or so. What policies will motivate more spending across all forms of viable energy?

Too many conversations, in particular those involving European energy and policy “experts”, various global elites, and climate doomsayers, are focused on whether we have the right or wrong kind of energy.

A good versus evil framework does not apply to Energy, in my view. Similarly, green versus brown or clean versus dirty are not actual energy supply categories. All energy sources have positive and negative attributes, which, in my humble opinion, is the better framing.

Important characteristics of energy include its relative abundance, affordability, reliability, and geopolitical security.

The number one moral goal has to be to provide energy for all: gross zero energy poverty. There is no logic to the concept of prematurely taking away some forms of energy deemed “bad” by various global elites and politicians.

In providing energy for all, we need to be mindful of negative externalities associated with various forms of energy, including emissions related to air quality, impact on biodiversity and other environmental factors, and its contribution to excessive carbon emissions.

Some of my favorite technologies that can contribute to gross zero energy poverty while minimizing negative externalities include nuclear power, natural gas/LNG, crude oil/refining, CCUS/DAC, near zero methane monitoring, electric and hybrid vehicles, and related infrastructure in all of these areas. Location specific technologies (i.e., applicable in niches) that are interesting include hydro power, solar (rooftop and utility grade), wind, geothermal, and heat pumps. Finally, all opportunities to improve energy efficiency in areas like building/residential heating/cooling and transportation sector fuel economy I believe should be pursued. This list is not meant to be exhaustive, with areas like hydrogen, battery storage, and many other future technologies worthy of study.

⚡️On a personal note…

We need diversity in the energy and climate discussion. It is a big reason I started Super-Spiked. And to be clear, I am not to referring to my parents’ Indian heritage. The energy and climate conversation is dominated by the very left-of-center on one side and the still left-of-center on the other. It’s not healthy or helpful and is leading to really bad outcomes: See Europe and California.

Where are the small “c” conservative voices on energy and climate? And I don’t mean the “climate is always changing, the Earth wobbles, carbon is great!” crowd. The universe of engaged capitalists that actually understand energy and climate appears to be quite small. The fact that the financial services industry is coming under immense pressure from those that purport to support markets and capitalism is the area I find most troubling. Munich Re’s deeply disturbing decision to exit traditional oil & gas reinsurance underwriting could be the start of a horrific trend that ultimately will negatively impact all of us (which I wrote about here).

While I remain hopeful that improved profitability from traditional energy coupled with the clear and obvious danger of following in Europe’s footsteps will stop the madness, that is not a given. Capitalism drives economic growth and the positive externalities that come from a more prosperous and less impoverished world. But economic growth is not without negative externalities often related to the environment, which does require rules and regulations. A limited government philosophy does not mean no government.

The voices demanding we deal with the negative externalities above all else are all we hear when it comes to energy and climate. Often, these voices are explicitly or implicitly anti-capitalism and pro-socialism (e.g., Green New Deal). Those that may still be supportive of capitalism and markets appear to believe in the magical thinking that we can “electrify everything, but only with intermittent energy sources.”

That is the Road to Hell as a prominent bank CEO recently quipped. Where is the diverse engagement in the energy and climate discussion?

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

📘Appendix: Definitions and Clarifications

All of the analysis in this post should be considered as “order of magnitude” and appropriate for long-term trend analysis.

The universe of companies included in the CAPEX and reinvestment rate analyses is the same as I use for the ROCE work. It is a 78 company universe of past and present publicly-traded traditional energy companies based overwhelmingly in the United States but also Canada and Europe. It includes major integrated and international oil companies, E&Ps, refiners, and oil service companies.

The data source for the ROCE and CAPEX analyses is S&P CapitalIQ. At Goldman Sachs, I would have relied on our own models that would have pulled from 10-Ks and equivalent documents for non-US companies.

All data is “as reported” and reflected by S&P CapitalIQ. The only adjustments I have made is to eliminate distorting mark-to-market hedge book adjustments in recent years from US gas-focused E&Ps.

Net income figures incorporated in the ROCE is “reported”. Most Street analysts are likely using company-disclosed “adjusted” earnings figures, something I would have previously done at Goldman Sachs. When looking at decadal time frames, I believe reported earnings is preferable.

Reinvestment rates measure CAPEX relative to cash flow from operations (i.e., the percentage of a company's cash flow that is being reinvested).

Free cash flow from operations is defined as cash flow from operations less CAPEX but before dividends and other capital returns to shareholders.

I would argue that these voices are not just anti-capitalism and pro-socialism, but in many cases anti-human. I was just watching an interview with renowned CPU architect Jim Keller by Jordan Peterson on the subject of the future of AI and Jim pointed out two things: 1. His children are basically being taught in university that humans are a virus on the planet and 2. he's an optimist that shares Elon Musk's view that we actually don't have enough people and we need more. I was trying to communicate to my own daughter this idea that the anti-human view is generally held by politicians and academics of little practical accomplishment, the optimist pro-human view is held by some of the worlds most prominent and practically accomplished intellects.

I love Super-Spiked! The best analysis out there today.

Question: does it make sense to say that the CAPEX deficit is well known, virtually everyone knows that capital is being constrained to the O&G industry, but few people are concerned about it because the general consensus is that it isn't a problem because global demand will peak soon based on the IEA/EIA's demand projections? And that the surprise, the 'aha' trigger moment, comes when the reality of sustained high global demand finally sinks?