Will oil demand go the way of coal demand? Oil bulls can only hope so, as global coal demand has yet to obviously peak and is believed to have reached an all-time high in 2022. As they say, reports of coals’ death have been greatly exaggerated. And let me be clear: this is not advocacy for or against coal. It's simply a fact: despite many forecasts to the contrary, coal demand has yet to enter a terminal decline state on a global basis.

Why has coal persisted and defied so many expert predictions? Because it's a massive low cost resource that is in great demand in particular in China, India, and other developing areas in Southeast Asia and Africa. If you are going to lift billions out of crushing poverty, you need energy that is abundant, affordable, reliable, and secure. Coal checks all four boxes.

It does not matter if my fellow, affluent Super-Spiked readers agree or disagree on whether the world should or should not use coal due to environmental and climate concerns. No one wants to or deserves to remain in crushing poverty and until we reach gross zero energy poverty, coal will likely prove too tempting to voluntarily ignore.

What about coal equities? There is no comparison between US-based coal equities and US oil and gas equities. Over my 30 year career, the US coal sector has, respectfully, always been at best a side-show; it’s not like it was once super important and then faded. Produced coal has been critically important to America’s development, but it did not to my recollection ever translate into an important publicly-traded sector. I am trying to think of a situation in another industry that is comparable. Perhaps department store retailers like Sears and JC Penney are sort of a comparable example. These were once important companies to many Americans, but I don’t believe they were ever “Nifty 50” leaders. To this day and despite the internet world we live in, there is still a substantial physical retail industry, but the old-school department stores are not relevant. Perhaps a reader can offer a better analogy.

This post is part 2 on my new "Extending the Runway" series (part 1 is here). The idea is to shift the conversation from simply a (much needed and not going away) profitability focus for traditional energy to one that looks to extend the period of advantaged returns and lower cost of capital. Discussing the notion of extending a period of advantaged returns by definition means introducing the concept of acceptable capital expenditures (CAPEX) versus solely returning cash back to investors. When cost of capital is high, the market is implicitly stating there is not confidence in industry (and/or companies) to generate sustained levels of acceptable profitability. CAPEX is disincentivized.

There is zero chance the world can live with disincentivized traditional energy sector CAPEX. We will not be moving to a healthier energy evolution era until we find a better balance between traditional energy CAPEX, policies that sensibly promote a healthy energy evolution, and recognition that a broad and inclusive array of old and new technologies will likely be needed. Especially if we are to meet the requirements of abundant, affordable, reliable, and secure energy that are sacrosanct. And, ideally, do this with an improving environmental and carbon footprint.

What oil markets can learn from coal: It's really hard to kill massive, low-cost resources humans need for development

If you are based in China, India, or Africa, I am sure you already know this. Not only is coal not dead, demand has been booming. That is not true here in the US…and wasn’t true in Europe until Russia gas suddenly went away and Europeans got a small, small taste of what potential energy poverty might mean…or they just don’t like high power prices. We shall see where long-term European energy policy heads; it seems painfully obvious to many non-European energy observers that some combination of nuclear power and natural gas/LNG will need to be part of their long-term energy solution. But it is up to European policy makers, or perhaps ulimtately its citizens, to chart a better course than the EU currently seems to be on.

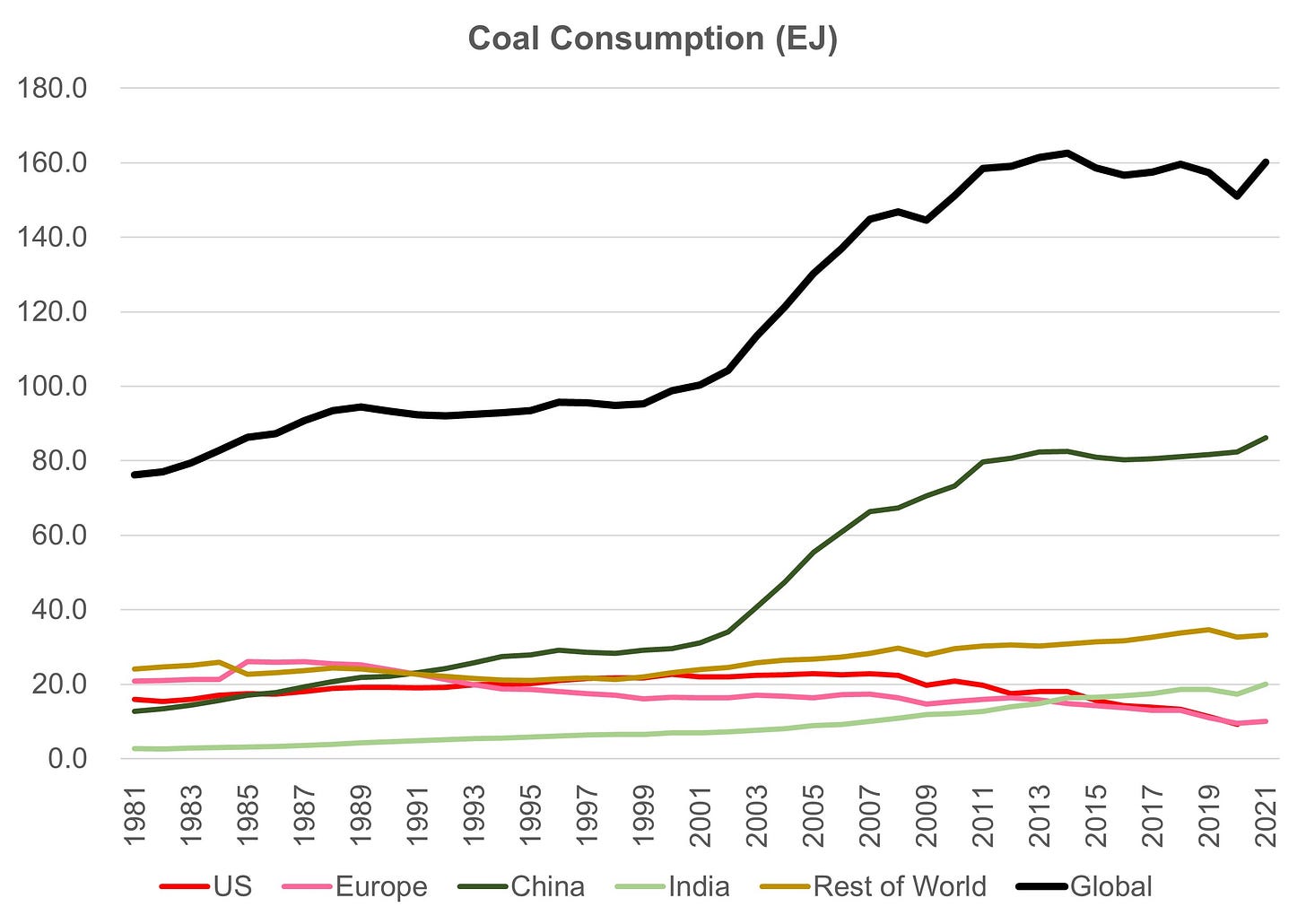

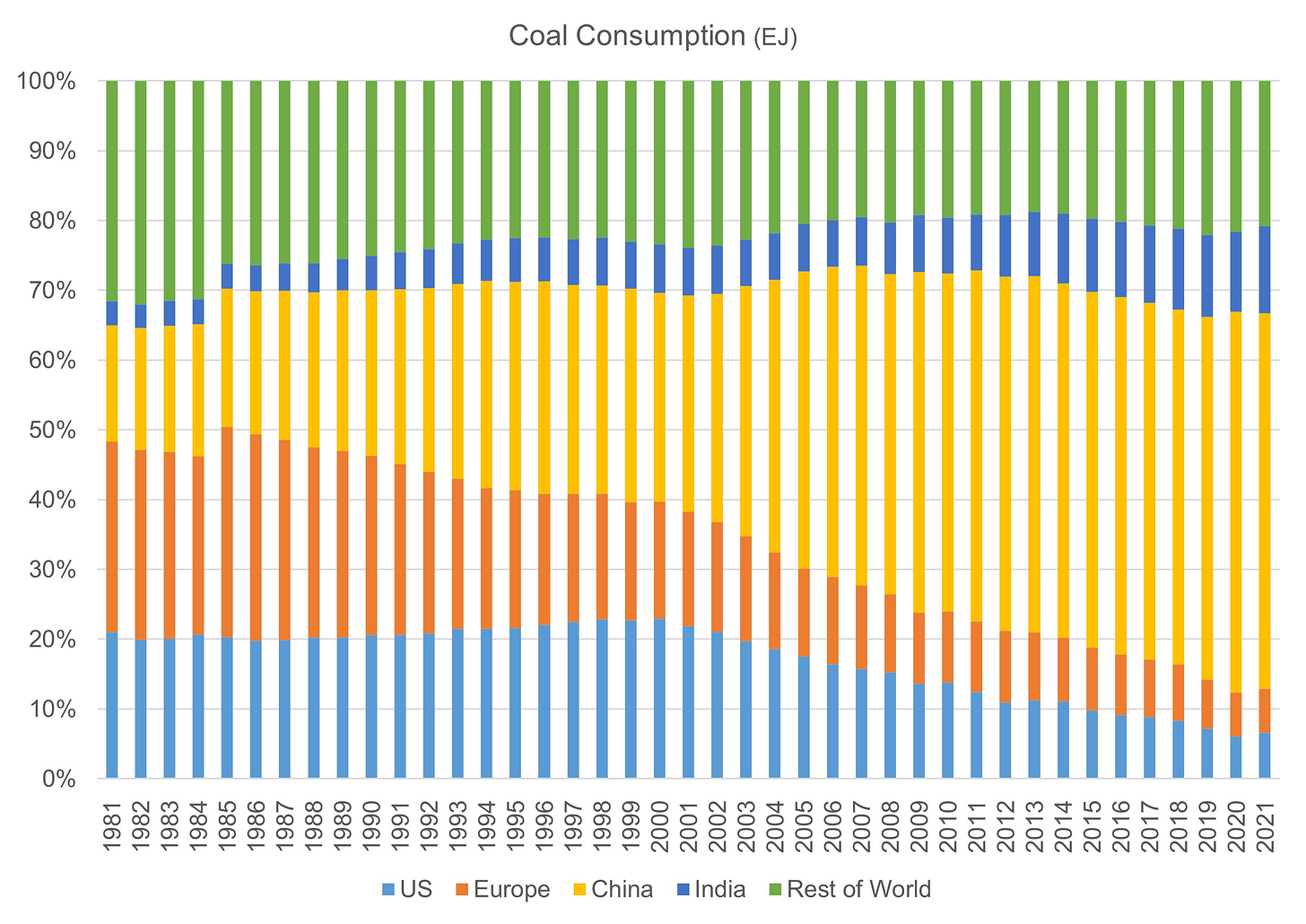

Exhibit 1 looks at global coal consumption by region and in aggregate; the units are exajoules. Exhibit 2 looks at the share of global coal consumption by region.

A few points:

US and Europe coal demand has been in long-term structural decline;

The first plateau in global coal demand was from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, with China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) the catalyst to a major boom in coal demand until the early 2010s.

China holds massive domestic coal resources, which provides significant domestic economic benefits (jobs, taxes, etc.) to go along with the basic need of available, affordable, reliable, and secure energy.

China’s economic miracle over the past 20 years has lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens out of poverty, arguably the most important “positive externality” from developing its coal resource.

On the flip side, coal production has resulted in traditional environmental harms and catapulted China into the leading greenhouse gas emitter on a current basis.

With China’s population on-track to head lower, it’s quite possible China is at or near “peak” coal demand. But peak and possible plateau or only modest declines are a far cry from sharp reductions. It is not clear to this observer when or what will be the catalyst for coal plant closures in China. As I understand it, China is still growing its coal fleet. (As a reminder, I am not a coal analyst; if you have a different perspective, please let me know).

Going forward, a few other questions loom large:

Will India follow in China’s footsteps? Like China, India has a massive domestic coal resource and perhaps an even larger need to lift even more people out of poverty.

If China, India, and other developing areas are going to move off of coal, what are the availability, affordability, reliability, and security attributes of alternatives? Again, the base-line is competition with a sizable, low cost domestic resource.

What mix of renewables, natural gas, nuclear, and other new or future technologies is needed that can solve the Big 4 challenges—availability, affordability, reliability, security—but with better environmental and climate characteristics? Non-China/non-India experts and policy makers do not get to choose the handful of characteristics that are important to them. If energy resources are not available or not affordable or not reliable or not secure, they will never be the first choice for a developing area.

In my view, there is zero chance 100% of any of the alternatives is possible, likely, or sensible. So it’s a question of what mix of the non-coal resources is reasonable and likely.

Implication of coal takeaways for oil markets: A terminal decline in oil demand is nowhere in sight

In the case of coal, there are many different ways to generate power, including, and in no particular order, renewables, natural gas, nuclear, fuel oil, diesel, and biomass. Yet, global coal demand has not obviously peaked let alone entered terminal decline. There must be a lesson in here somewhere! Lots of choices on how to generate power, but the world is still using a whole bunch of coal.

In the case of oil, there are far fewer alternative commercial ways to meet transportation demand. This is in sharp contrast to coal, where there are many more viable alternatives yet coal demand has not definitively peaked. In transportation markets, electric vehicles (EVs) have shown they can be competitive in luxury/mass affluent markets. Whether the developing world in particular can go even partially let alone mostly EV any time over the next 30-50 years, especially using current battery technology, is highly uncertain. There is no chance that the bottom (economically) 5-7 billion people on Earth are on-track to go 100% EVs this half century.

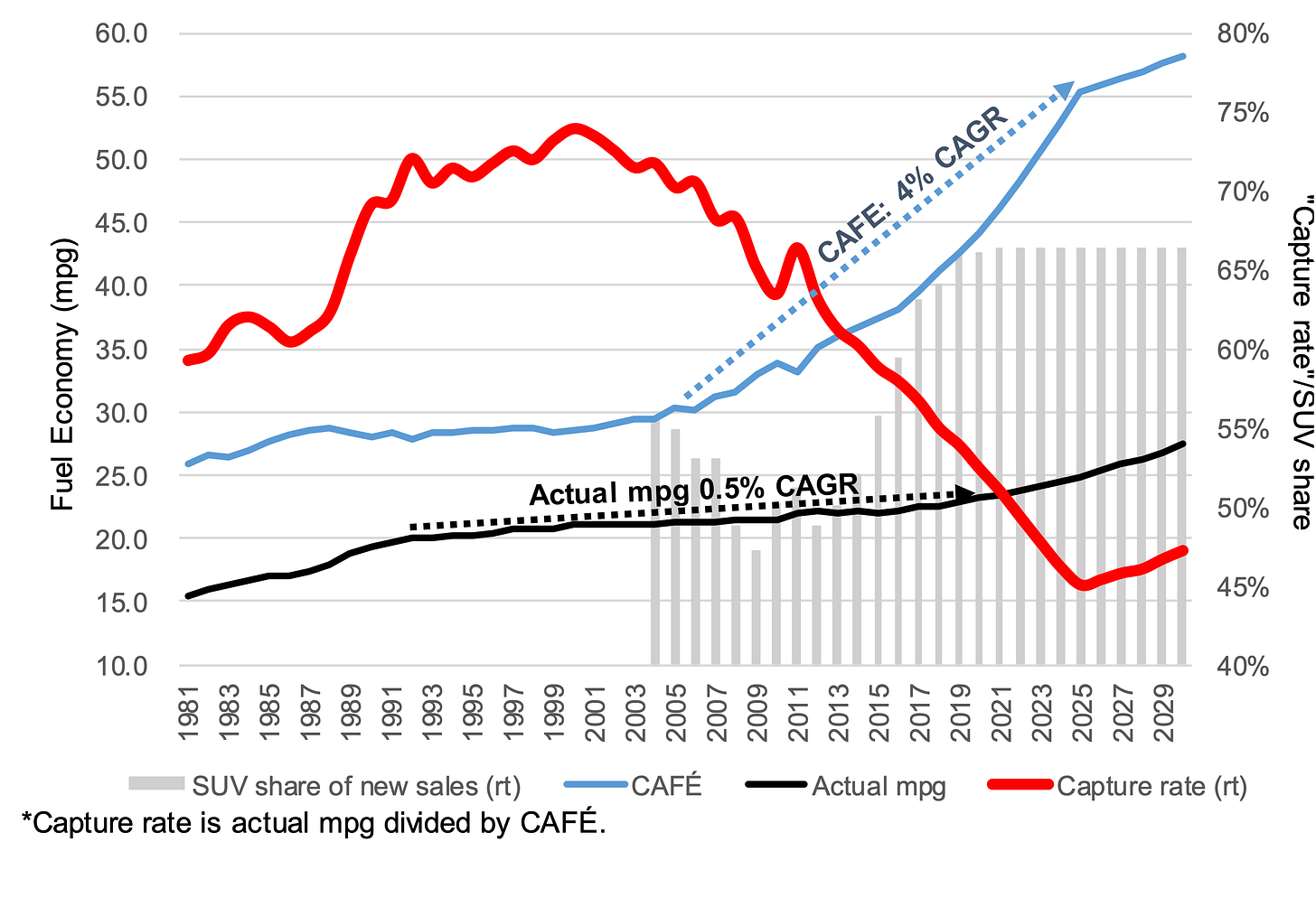

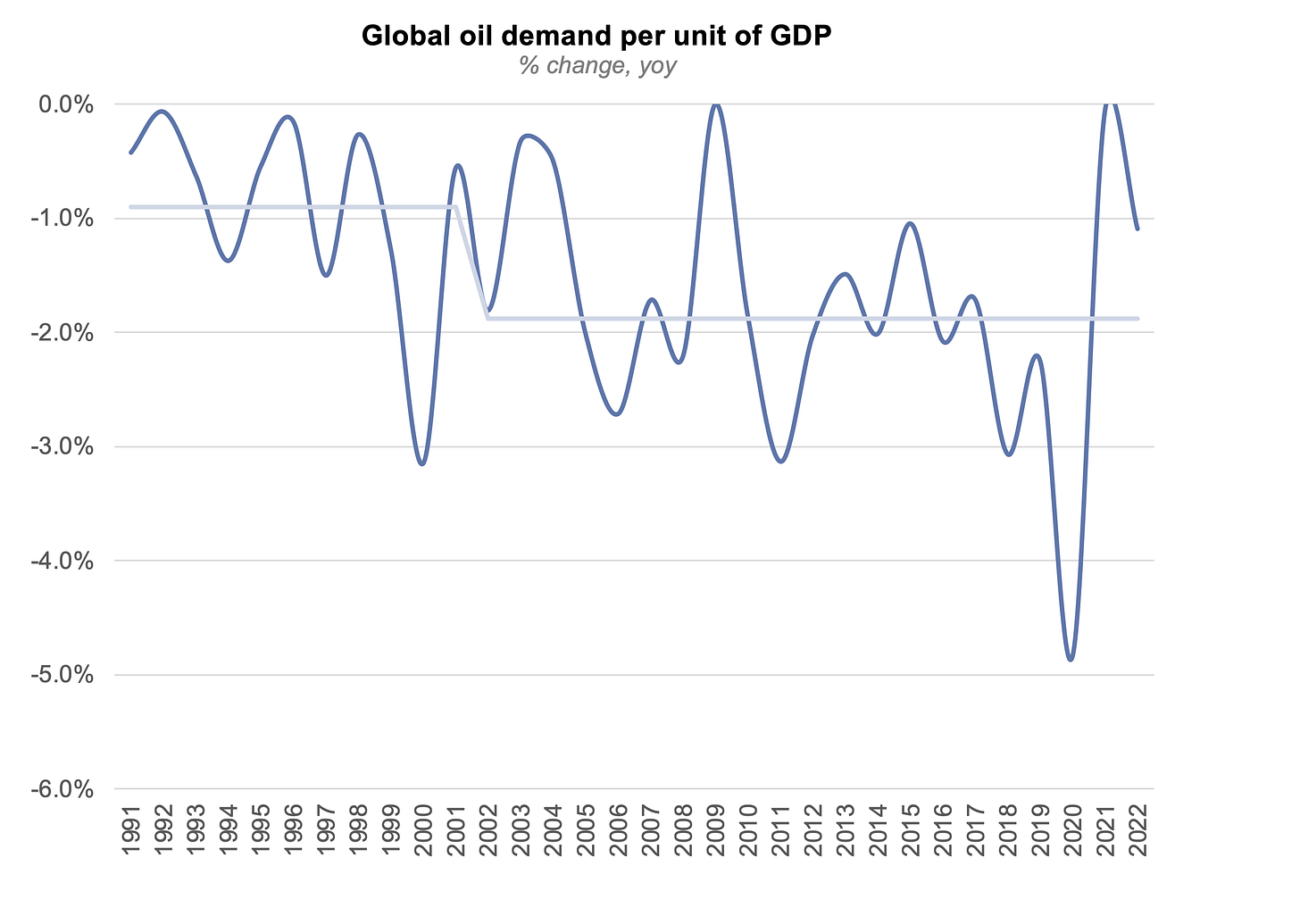

In my January 14, 2022 videopod Free money bubble stocks, EV hockey sticks, and oil demand (here), I laid out the challenges with the bear case for oil demand. In a nutshell, for oil demand to plateau and then enter terminal decline, a combination of accelerating efficiency gains plus a material ramp in EV sales are BOTH needed; neither seem to be on-track, in my view. See Exhibits 3-6.

Exhibit 3: The IEA’s (deeply unfortunate? calamitous?) “Net Zero by 2050” report lays out a scenario that calls for sharp declines in oil and natural gas demand by 2050. WIth oil, that would mean (1) a sharp increase in efficiency gains and (2) “hockey stick” EV penetration ramp.

Exhibit 4: There is zero evidence efficiency gains are on-track to accelerate; for example, as this exhibit shows, US mpg trends miss government mandates by ~80%-90% due to the “SUV-ifiation” of our vehicle fleet.

Exhibit 5: The same is true when looking at global efficiency gain statistics. Global GDP grows faster than oil demand, but the slope of the trend line is flat over the past 20 years; to achieve net zero objectives, oil demand would need to decouple on the downside at an accelerating clip relative to global GDP growth.

Exhibit 6: I am bullish EV sales, but do not see the “hockey stick” forecasts as being realistic for a variety of reasons related to affordability, infrastructure, raw materials challenges, grid challenges, among other concerns. I expect EV sales AND oil demand to both grow over the next 10-15 years.

Lessons for oil and gas investors from US coal equities: Stay profitable, stay relevant

A topic among market participants has been whether US oil and gas equities will go the way of coal equities in the sense of the sector generally becoming uninvestable. The term uninvestable in this case likely means two main things:

A low index weighting of the sector combined with a lack of profitability and inherent volatility means investors will generally think it is not worthwhile doing the work to invest, even on the occasions where industry conditions are favorable;

It is "socially" unacceptable to be seen as an investor.

The second point on “socially unacceptable” is the older notion of the term and I don't mean it in the contemporary ESG sense, though there is no doubt ESG investors would avoid the sector. Rather it means the bucket of companies or sectors outside the mainstream, which includes areas like cannabis, adult entertainment, and firearms manufacturers.

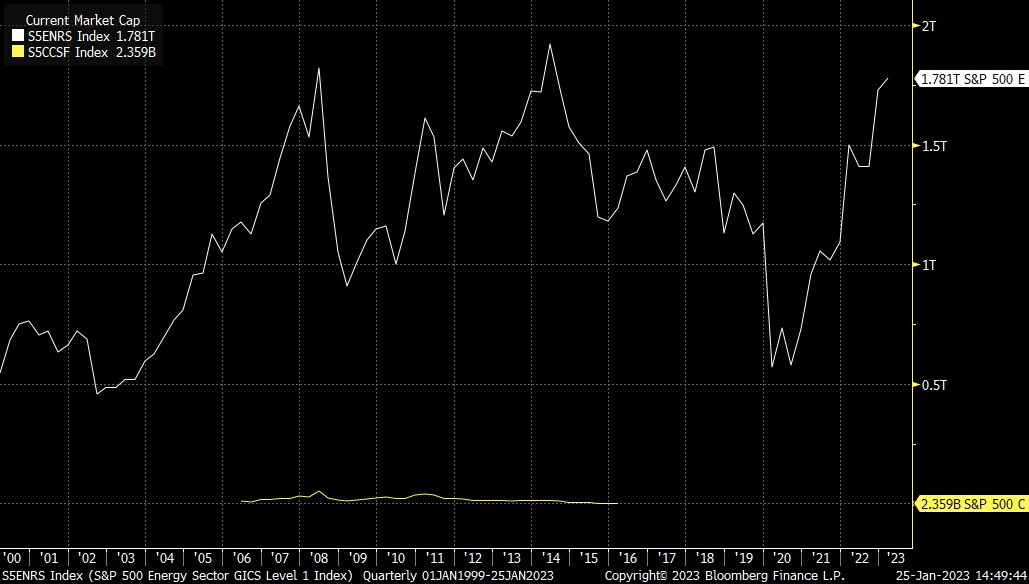

The thing is coal has never been super investable, at least not over the past 30 years I have been looking at energy. Exhibit 7 shows the equity market capitalization for all energy stocks in the S&P 500 (S5ENRS Index), which is the white line versus the Coal and Consumable Fuels sub-index (S5CCF Index). Apparently, the coal sub-sector was only broken out from the rest of energy from 2005 until 2016. From a mainstream Wall Street investment standpoint, coal has never been a “real” sector that investors or analysts covered. I really mean no disrespect to any coal companies in making this comment; I am just observing investable market capitalizations. Bloomberg’s y-axis naturally scaled to trillions of dollars. Coal hugs the zero line; the y-axis is drawn to dip into negative values so you could actually see the coal line. Coal is not nor has it ever been, at least not in the past 30 years, a relevant Wall Street sector.

Exhibit 7: US oil and gas market capitalization (in the S&P 500) regularly measures in the $trillions; Publicly-traded coal equities are not even a blip on institutional investor screens.

When you hear about financial institutions declaring they will no longer invest in coal, you have to wonder how robust was any of their coal investment pipelines in the first place. The market capitalization has almost always been too small for most major institutional investors. To my knowledge, there has never been a robust pipeline of private coal investment opportunities. There hasn’t been a rich pipeline of coal initial public offerings (IPOs).

It’s kind of like vowing to never, ever invest in an oil drilling program onshore Antartica. Or as a US investor, swearing off North Korean e-commerce plays so long as Kim Jong Un is in charge. Swearing off coal has been essentially risk-free virtue signaling for the vast majority of institutional investors. Similarly, it really hasn’t had any real-world consequences since China and India have been able to develop their coal resources with their own companies.

None of this would be true for oil and gas. It has been and could again become a major sector as indicated by major index (i.e., S&P 500) weightings. Oil and gas companies are capable of and in fact are already starting to generate meaningful earnings and cash flows. The US (and Canadian) oil industry is critical both to our prosperity and global economic health.

So while I agree that cost of capital for traditional energy is high at the moment, I still attribute the high cost of capital to (1) the super-challenging 15 year period ending in 2020, and (2) concerns about long-term demand uncertainty due to energy transition. There is little doubt in mind that as or if traditional energy companies continue to earn competitive ROCE, capital will flow back to the sector…and in a big way. I do NOT see univestability as arising on moral grounds or in the sense of oil and gas becoming “the next coal”. We have already seen the sector’s weighting go from an all-time low of 2% of the S&P 500 to just over 5%. I expect traditional energy will again reach a mid-teens % of the S&P 500 within the 2020s before the current cycle ends.

⚡️On a Personal Note

A topic that is frequently discussed by non-climate hawks involved in the energy & climate discussion is the notion of the “demonization of the oil & gas industry” and how unfortunate that has been. I share the view it is unfortunate. However, this commentary on coal versus oil and gas has reminded me that those of us that favor a healthier approach to traditional oil and gas may not be sin-free when it comes to demonizing alternate energy sources.

My career began in the early 1990s in Denver, Colorado with a focus on US natural gas-leveraged E&Ps. I know I regularly and without thinking twice about it discussed my positive view for long-term natural gas demand as in part being driven by natural gas being an excellent “transition fuel” that was cleaner burning than dirtier coal (meaning lower carbon emissions and overall better environmental performance).

The language I think is noteworthy in retrospect. Keep in mind this is the early 1990s.

I (as did most E&P analysts) described natural gas as a “transition fuel”, implying it would get displaced by something else in the future, presumably nuclear or renewables.

We all described it as cleaner burning than “dirty” coal.

Was that language really that much different than what we hear from climate hawks today about the oil and gas industry? Yes, there is a bunch of other annoying progressive ideology mixed into today’s climate discussion where as Wall Street analysts we were more focused on economics and macro and company outlooks. But still, I am not so sure the intent of the language is that dissimilar.

Since the 2000s, the transitional fuel language around natural gas seems to have mostly faded from Wall Street talk. This is likely driven by the fact that US natural gas has now displaced significant quantities of US coal, and as the shale oil boom shifted emphasis back to crude oil as the key focus area, rather than natural gas.

This section suddenly seems on-track to turn into its own 2,000 word commentary, so let me simply assert:

I believe there is an inconsistency on my part to have effectively demonized coal in the 1990s, but to now take issue with oil & gas being demonized.

I think the “transition fuel” language for natural gas was incorrect; it is simply an energy source, full stop, that has certain availability, affordability, reliability, security, environmental, and climate characteristics.

Coal is also simply a fuel, with its own set of characteristics, some of which are better and some of which are less favorable than competing fuels.

I would like to publicly apologize for the lazy and not well thought out language I used at the beginning of my career in describing coal as dirtier than natural gas. More recently, I don’t think I have used this language, though I need to give some thought to how I am currently describing LNG as being critical to displacing coal in China and India.

Coal of course does (usually) burn with a higher carbon content. It is also abundant, affordable, reliable, and secure for developing countries like China and India and will contribute to hundreds of millions and possibly a billion-plus people being lifted out of poverty in coming decades. It no more deserved or deserves to be demonized than does the oil and gas industry. I am sorry for having done so in the past and I will aim to be more mindful of the language I use going forward.

🎤 Streams of the Week

Streams of the Week features back-to-back episodes published around year-end 2022 by one of my weekly must-listen podcasts, MacroVoices. I have included links to the MacroVoices website, but you can also find these episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or via your favorite podcast player app. You can think of the two episodes as a “Nuclear 101” for those interested in the topic.

MacroVoices, Episode #355: Mark Nelson: Understanding All Things Nuclear: link

MacroVoices, Episode #356: Justin Huhn: Investing In All Things Nuclear: link

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Arjun. followed you for years at GS . Really appreciate this substack, as given the decimation of the sector in the 2010's, there just aren't many intelligent voices left on Wall St. remaining. Given Energy's importance to the world and clear mismanagement of the transition to this point by the West, its great you are spending the time to educate. We can only hope some leasers hit the "subscribe" button.

A couple of comments ask if there are any major commodities other than whale oil that have gone out of use. The most relevant example I can think of are the ~100 chemicals that fall under the category of ozone depleting substances. Relevant because these chemicals were a real risk to the human population globally and because nations around the world came together to phase them out.

Relatedly I don’t think there’s anything wrong with calling coal dirty. If ever there was a dirty mass source of energy it’s coal — the deadliest form of energy by far.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/death-rates-from-energy-production-per-twh