Cost Curve Evolution, Diversification, Cost of Capital, and Avoiding Purgatory

Extending The Runway

Pure play or diversified? Which is the better business model in the long run?

There are three good long-term outcomes for publicly-traded traditional energy companies:

Outperform the S&P 500 (or corresponding major benchmark if not US-based) over 5, 10, and 20 year increments.

Sell or merge with another company.

Liquidate and return all cash back to shareholders.

There are two bad outcomes:

Bankruptcy and the elimination of equity value.

Purgatory: Fade to “living dead” status where the company trails the S&P 500 and becomes irrelevant to most investors, though otherwise remains viable.

While purgatory may seem obviously preferable to bankruptcy, the opportunity cost of relative underperformance can be massive. At least with bankruptcy, you absorbed the pain and moved on. Purgatory is the #1 risk most investors of traditional energy equities face: A languishing stock price and the realization that a host of alternatives—cloud computing infrastructure, real estate, health care, consumer durables, aerospace, industrial technology, financial technology, a yield oriented renewables fund, etc. etc.—would have been a better use of your capital.

The purpose of this post is focused on achieving the first good outcome—sustainable share price outperformance versus the S&P 500—and avoiding the purgatory of lackluster viability. I expect this will be a multi-part series on “extending the runway” of asset quality and duration to ensure multi-decade outperformance potential: i.e., sustaining the period of advantaged ROCE and lowering cost of capital.

When one considers cost curve evolution and the fact that various plays and regions come in and out of favor over time, I suspect that just about all companies that strive for successful going concern status will need to have diversified exposures over time, including across different basins/regions/countries/plays. With that said, companies with multi-year, single basin running room might well have time to evaluate strategic options. The inevitability of diversification, rather than a sense of urgency, is more the point of this post.

My last two videopods (here and here) addressed two of the questions posed in my New Years Day Five Questions At The Start of 2023 post. This week I turn to two related questions about the nature of upstream business models in a world where there is no longer any tolerance for poor returns on capital employed (ROCE), growth metrics are de-emphasized, shale is maturing, and the commodity backdrop is best described as "Super Vol" rather than "Super Cycle".

On January 1, 2023 I asked:

In a world that favors ROCE and dividends, is a diversified E&P business model preferable to being a pure play?

My view: Yes, in many cases.

The logical follow-up was:

How can an E&P company add duration and diversify without upsetting investors in the short term?

My view: It's tricky, case specific, and may not be possible...i.e., it may not be possible to not upset investors.

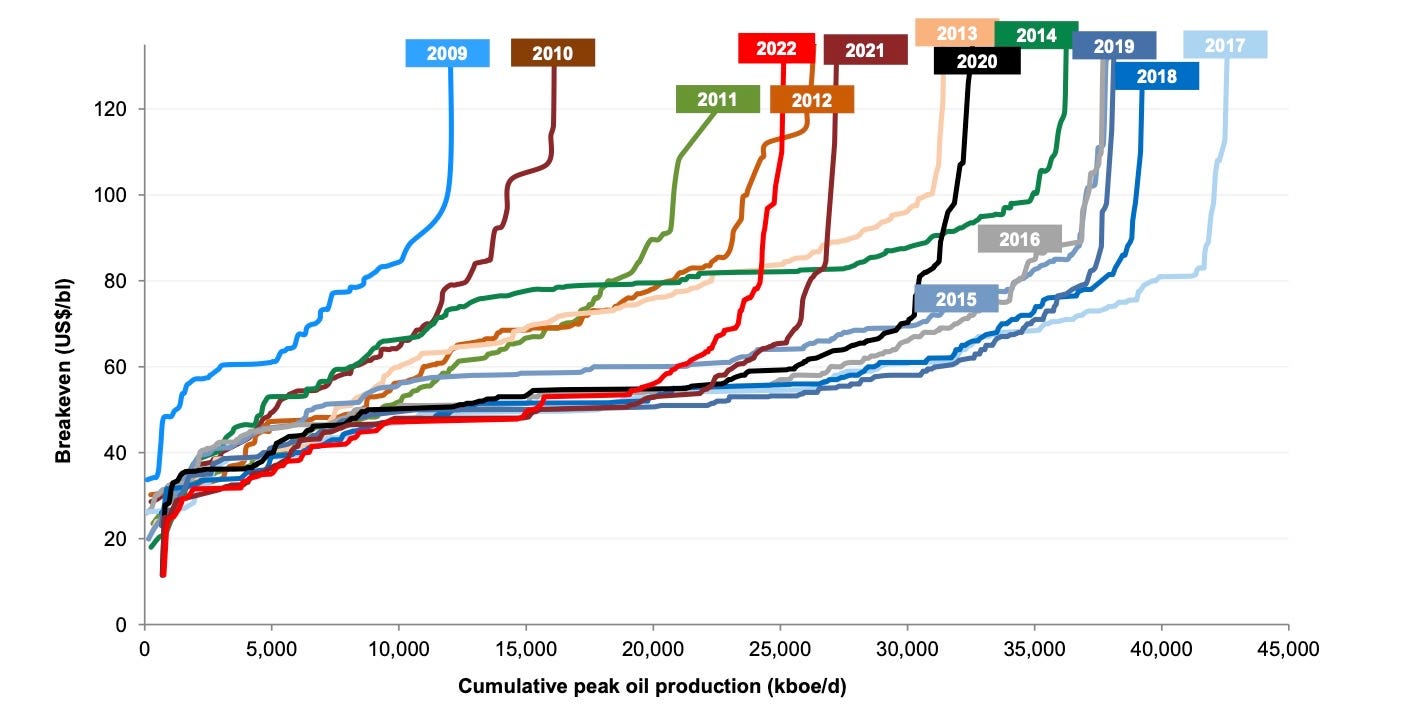

Crude oil and natural gas cost curves are not stagnant

One of the areas that makes traditional energy so interesting…and difficult to predict…is the nature of cost curve evolution. Exhibits 1 and 2 show work I contributed to at Goldman Sachs that the team continues to update via their flagship Top Projects report series. Most noteworthy is the observation that crude oil and natural gas cost curves are not stagnant over time (Exhibit 1). In fact they shift a lot. Additionally, within a region there can be quite a lot of variability in terms of low, medium, and high cost projects/areas (Exhibit 2).

All else equal, a cost curve that is steepening and narrowing is a sign of tightening oil (or natural gas) markets, which you can see is happening over 2018-2022 in Exhibit 1. The narrowing in this sense means there are simply fewer resources at any given supply cost to be developed. A flattening and expanding cost curve typically means large quantities of lower cost resource are being added; 2010-2013 was the forewarning to the 2014-2020 bear market.

In both scenarios, intra regional shifts can vary differently from the broader trend. For example, US shale oil was originally considered “very high cost”. However, as it became apparent that increasingly sizable volumes could be developed, and as learnings lowered development costs, the shale cost curve drove an expansion and flattening of the global oil cost curve.

A few additional points:

Today’s apparent low cost resource can become tomorrow’s legacy high cost play. A natural gas example would be the Pinedale Anticline (Wyoming) being undercut by the Barnett Shale (Texas) which was subsequently undercut by the Marcellus Shale (Appalachia).

Within a basin, acreage is rarely homogenous meaning the intra-basin cost curve can be surprisingly steep. Today we might differentiate in the Permian Basin between Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 inventory quality.

As one of my all-time favorite CEOs, Tom O’Malley of Tosco fame, revealed in the 1990s, acquiring a historically higher cost asset for “pennies on the dollar” can prove to be an excellent strategy. In his case it was in the refining business, but this can be applied to upstream assets as well.

Both companies and investors will bid up and bid down various plays. “Buy low, sell high” is not as easy as it sounds when a major basin heats up.

A natural gas example: Fayetteville & Barnett to Marcellus

Exhibit 3 looks at the share price performance of three natural gas-leveraged E&P companies—Cabot Oil & Gas, Southwestern Energy, and Quicksilver Resources—as well as the energy names in the S&P 500 (S5ENRS). The significant outperformance of Southwestern and Quicksilver in the early-to-mid 2000s came from the initial shale gas ramps in the Fayetteville and Barnett Shale plays, respectively. The subsequent underperformance of both companies was a result of: (1) lower gas prices due to oversupply from the initial shale gas plays (i.e., Fayetteville, Barnett, and elsewhere); and (2) the Marcellus Shale eventually undercutting the previous shale gas basins on the cost curve, with Cabot Oil & Gas among the leaders in the Marcellus.

The key message: Single basin success did not lead to sustained outperformance, though the initial gains were substantial. Quicksilver eventually declared bankruptcy. Southwestern persisted in purgatory mode for a decade-plus. To its credit, Southwestern may have again found a forward-looking footing based on its share price outperformance since 2020 (not shown above; admittedly, I do not follow SWN as closely as I once did).

An oil example: Oil sands to Permian (back to oil sands?)

An oily example I would highlight is Canada’s oil sands region versus the Permian Basin, which, quite possibly, might swing back towards Canada over the next decade. Suncor Energy and Canada’s oil sands region re-rated significantly higher during the initial Super-Spike years of 2002-2006 as it became apparent that oil prices would be much higher than the 1990s and as the world sought to develop major new sources of oil supply. Ultimately, massive shale oil resources in the United States undercut Canada’s oil sands, with the Permian Basin turning out to be the king of the US shale oil basins. I am using Pioneer Natural Resources shares to illustrate the outperformance of many Permian producers over the 2009-2014 period.

I will say that this story is not over yet. Long-time Super-Spiked subscribers are well aware of my view that a return to Canada’s oil sands regions will be one of the signs we are on-track for a healthier energy evolution era.

I would also note that a major part of the negative impact to Canadian oil sands producers over 2015-2020 came from the willingness of the US shale industry to accept below cost-of-capital returns. Given the massive resource but bite-sized scalability of the shale resource, the bottom line impact was indeed negative to Canadian oils. But it’s an important distinction to make: I don’t believe Canada’s oil sands region is uncompetitive with shale (on average). It simply requires much larger upfront capital and an unavoidable inclusion of full-cycle spending. From the perspective of an investor, the fact that US shale producers accepted a 0% ROCE last decade was a negative read through to the performance of Canadian oils.

2023-2024 Outlook: The need to address cost of capital

I suspect there isn't a single Super-Spiked subscriber that is unaware of my emphasis on sustained profitability improvements for the traditional energy sector, which I short-hand as return on capital employed (ROCE). Over the course of 2021 and 2022, both individual companies and the sector broadly have made dramatic improvements to both current and expected profitability levels (see Exhibit 5). I believe 2023 and 2024 will be about solidifying those gains (on a through cycle basis), with a growing need to work on reducing cost of capital.

Despite being up sharply off October 2020 lows, traditional energy continues to trade at discounted valuations. In my view, commodity volatility is a fairly obvious albeit limited explanatory variable. Commodity volatility is not new. And while the ROCE acceleration off trough has been more extreme than in the past, I believe it is increasingly broadly understood that (1) CAPEX is low; (2) traditional energy markets are likely to remain reasonably tight over the next several years at a minimum, and (3) companies are more dedicated to prioritizing ROCE and cash returned to investors over growth than at any point anyone can ever remember.

Yet, energy continues to meaningfully under-punch its earning weight in the S&P 500 (Exhibit 6). Free cash flow yields for mega-cap bellwethers like ExxonMobil and Chevron are meaningfully discounted from other stock market leaders (Exhibit 7). On a multi-year basis, traditional energy is still badly lagging "innovation" stocks, ETFs, and sectors despite the latter groups having fallen by 70%-80% over the past 12-18 months (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 6: Energy typically “punches its earnings weight” in the S&P 500…currently its market cap weighting is about half its earning weight

Exhibit 7: Energy bellwethers XOM and CVX trade at meaningfully more expensive free cash flow yields versus other stock market leaders

Exhibit 8: Despite sharp energy outperformance in 2021 and 2022 and a collapse in many of the previous high fliers, energy is still lagging when looking over a longer time frame

Cost of Capital Drivers

There is likely no one single variable for the higher cost of capital facing traditional energy. Possible explanations include:

A lack of confidence that improved ROCE is sustainable due to uncertainty that potentially higher commodity prices will flow through to bottom line results due to a lack of advantaged drilling inventory;

Questions on the timing and pace of “energy transition” and the outlook for long-term oil demand in particular;

Recession concerns and the potential for lower commodity prices over the next 12 months.

What is the objective:

Extend the period by which a company generates better than cost-of-capital through-cycle ROCE; let's call it a 12% or better ROCE versus an industry average 8%-10% over a full cycle.

Increase acquisition and investment optionality for the purpose of extending advantaged ROCE duration; the goal is not growth for growth's sake or classic empire building.

Dissuade Street analysts and investors from focusing on volume growth and instead shift to growth in non-variable (i.e., base) dividends and overall cash returned to investors.

Maintain a fortress balance sheet as the best means to withstand inevitably high levels of commodity price volatility and improve the odds of successfully investing in a counter-cyclical manner.

Addressing investor concerns about di-“worse”-ification

Investors have understandable fear about di-"worse"-ification. Key concerns include:

Companies add projects/assets in areas where management does not have advantaged expertise, resulting in execution disappointment.

Managements are more interested in empire building and adding size, which often correlates with higher executive compensation.

Diversifying (especially if previously a pure-play) reduces the odds of being a takeover target.

Pure-plays that generate high ROCE typically receive premium valuations on traditional institutional investor metrics such as EV/EBITDA (or DACF); some pure-plays that don't generate competitive ROCE similarly receive premium multiples on the hopes of better ROCE in the future.

Rather than use financial capacity to diversify, companies should return cash capacity to investors, which provides greater return certainty than an acquisition.

The investor concerns have merit. Here is how I would address each point:

(Lack of) Expertise: Companies should consider taking a page out of the private equity playbook and add management or advisor expertise in new areas.

Empire building: The proof will be in the future financial results. If competitive ROCE and free cash flow is ultimately generated, I have no issue with how large a company becomes.

Avoiding takeover: This is at tricky one, as it feels like it would be true that a pure-play would have a higher probability of takeover than a diversified entity. In my view, companies need to weigh the benefits of sale or merger versus expansion. A sale or merger may not always be the best option, even as upfront premiums can be tempting to short-term investors. Moreover, it’s not clear to me that diversified E&Ps have NOT been taken over historically; in fact, many have (I will follow-up on this point in a future post).

Pure-play valuation premium: This is basically the point of this note. The valuation premium will only last so long as incremental results are favorable. When acreage results start heading south; it’s game over and often quickly.

Return cash instead: This falls in the same bucket, broadly speaking, as the “avoiding takeover” critique. It can certainly feel good to receive a current cash payment. However, an acquisition that actually generates superior ROCE will be better in the long run…it’s a big IF, for sure.

⚡️On a personal note…

A personal challenge I am starting to face is how to maintain the much healthier work-life balance I have enjoyed post Goldman Sachs. As my children leave for college, a new energy upcycle is upon us, and there is a need for much greater balance and diversity in how best to effectuate a healthier energy evolution era (i.e., non-progressive viewpoints are desperately needed), I need some guardrails to not regress back to Goldman-like intensity.

I am going to go with a single metric for work-life balance: # of golf rounds played, including posted scores during the season plus offseason rounds. Over 2015-2021, I averaged 102 total rounds per year; in 2022, rounds dropped to 72 as a heavier post-COVID travel schedule had a major negative impact on rounds played.

Based on the core US Northeast playing season of April through October, 7 months x 4 weeks x 2 rounds per week equals 56 rounds. Add in 5-10 off season rounds and something like 60-65 rounds seems like an achievable objective. One of the keys for 2023 will be to incorporate more rounds into travel. If I am coming to your city, please let me know if we can get out to your course.

I believe a quality metric on rounds played needs to be included, as it will ensure practice time is not cheated in lieu of “getting in a counted round” to hit a goal. My GHIN index has fallen from something like 36 when I first took up the sport in 2014 (I can’t find the exact number but this is a close approximation) to my current 7.9 (note: posting ends in the US Northeast in November and doesn’t resume until April). Not sure if it is a coincidence or causal, but 7.9 is my all-time low and comes during a down-year for rounds. Less is more?

On the index, I am fighting age, but there is still room for improvement in the short game. I also play with enough people older than me who are not obviously more athletic to realize the end is not necessarily near for my golf game. If I am asking oil companies to achieve full-cycle ROCE of at least 12%, I should similarly strive to keep a single digit GHIN in 2023.

🎤 Streams of the Week

As I first noted in the New Years Day post, I am an avid podcast listener, with circa 90 streams (audio and on YouTube) to which I subscribe and will regularly highlight favorite episodes from recent weeks. Below I am including YouTube or Substack links, but these are all available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or via your favorite podcast player app by searching for the named episode.

Smarter Markets: Energy Investing in 2023

I think some of you have already listened to this. I really enjoyed my discussion with former colleague Dave Greely.

Autoline After Hours #629: What did the Auto Industry in ’22 Teach Us About ’23

An excellent discussion on the outlook for the Autos sector including EVs for 2023 and coming years. They have a shorter (8-10 minute) daily show to catch-up on news, with the “After Hours” weekly program a longer discussion on auto sector themes.

Volts (Substack): Working on the cheapest possible lithium-ion battery

David Roberts is a climate journalist and someone who I enjoy listening to (or reading) even though I don’t usually agree with his decidedly left-of-center commentary. If you put the ideologically-driven conclusions aside, the underlying content is often quite interesting and I rarely miss an episode of Volts (here).

It’s not a question of always agreeing with him or his guests. I think it is important to listen to different viewpoints, which have helped refine my own. I am not a paying subscriber of Volts as a (small) protest against partisan commentary. But I will give Mr. Roberts credit for having sincere, strongly held beliefs—a point we have in common even if those views are often opposing.

I thought this discussion on lithium ion batteries was particularly relevant to the outlook for EVs. In this case, I believe the conclusion from the guest is similar to my own: You won’t be getting to 100% EV market share anytime soon and certainly not with current battery technology.

💿 Energy Transition Playlist 📼

It’s been a while since a new addition has been warranted. But you can’t discuss “Purgatory” in a post without immediately thinking of the pre-Bruce Dickinson (lead singer) classic from Iron Maiden’s second album, Killers that featured Paul Di’Anno on vocals. Killers is on the list of all-time greatest albums ever. The full energy transition list can be found on YouTube or Spotify.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

One more quick comment. Let's not forget the Clearwater play in the Marten Hills, Charlie Lake area of Alberta. Hottest heavy oil play going now with about a dozen operators participating. High perm sandstone with low viscosity 20 degree oil. No fracs or steam injection required. Cheers

Wow...I learned something here. I didn't know there was a pre-Bruce Dickinson version of Iron Maiden. Shame on me-big fan. Fave Iron Maiden concert- Samba Drome, Rio de Janeiro 2009.

Too much here to assimilate and comment generally except lots of good stuff in this post. I agree on the Canadian oil sands producers. Technology is evolving in this space. Unit costs are coming down. Canadian Natural Resources, (CNQ), Suncor, (SU), MEG Energy, (MEGEF) are my top picks. Cheers and thanks for all the good info!