Top Ten Tactical Predictions for 2026

Navigating The Energy Macro

On January 10 we published our Big Themes for 2026 (here) and, as promised, we are following up with our specific predictions for the year. This year we adjust the approach to our tactical calls to be as much about what we think the most important areas to watch are and which tie into the longer-term mega themes we wrote about in the January 10 post. Our 2026 predictions fall into the buckets of macro, corporate strategy, markets and sectors, geopolitics & policy, and the environment & sustainability. If you want to see how we did last year, you can find our 2025 Big Themes, tactical questions, and year-end evaluations here, here, here, and here.

MACRO

Super-Spiked Prediction #1 (P1); Will we see a virtual cycle of expanding global GDP growth in 2026 that is driven by growing energy access?

Answer (A): Yes.

We believe many of the trends that are considered energy oriented such as rising renewables and EV (electric vehicle) penetration in the developing world, industrial manufacturing competition between China, the United States, and the Rest of World, and AI (artificial intelligence) and broader digital transformation is positive for global GDP growth.

Growing energy access is positive for economic activity. We have noted in prior posts or video podcasts that we see a virtuous cycle between a specific energy source or technology gaining traction, economic activity, and growth in other energy sources and technologies. Our favorite example at the moment is renewables penetration in various African countries leading to higher oil demand.

Manufacturing “reshoring” competition we also see as positive for economic activity even as it almost certainly contributes to higher inflation (versus what would otherwise be the case). We have observed that since 2018, the world economy has been stuck in a slower gear, well below the boom days of China/BRICs expansion from 2004-14 but even below the pre-China/BRICs 1990s. Faster global GDP growth is positive for all forms of energy.

AI and broader digital transformation which includes themes like autonomous mobility, robotics, and space—including the geopolitical competition and desire to “win the race” for XYZ technology—we see as bullish for economic growth and energy demand.

P2: Will we see tangible proof the U.S. will successfully re-accelerate power market growth, and if so, how much of the growth gap with China can it close?

A: Yes and there is a reasonable path to growing between one-third and half as fast as China.

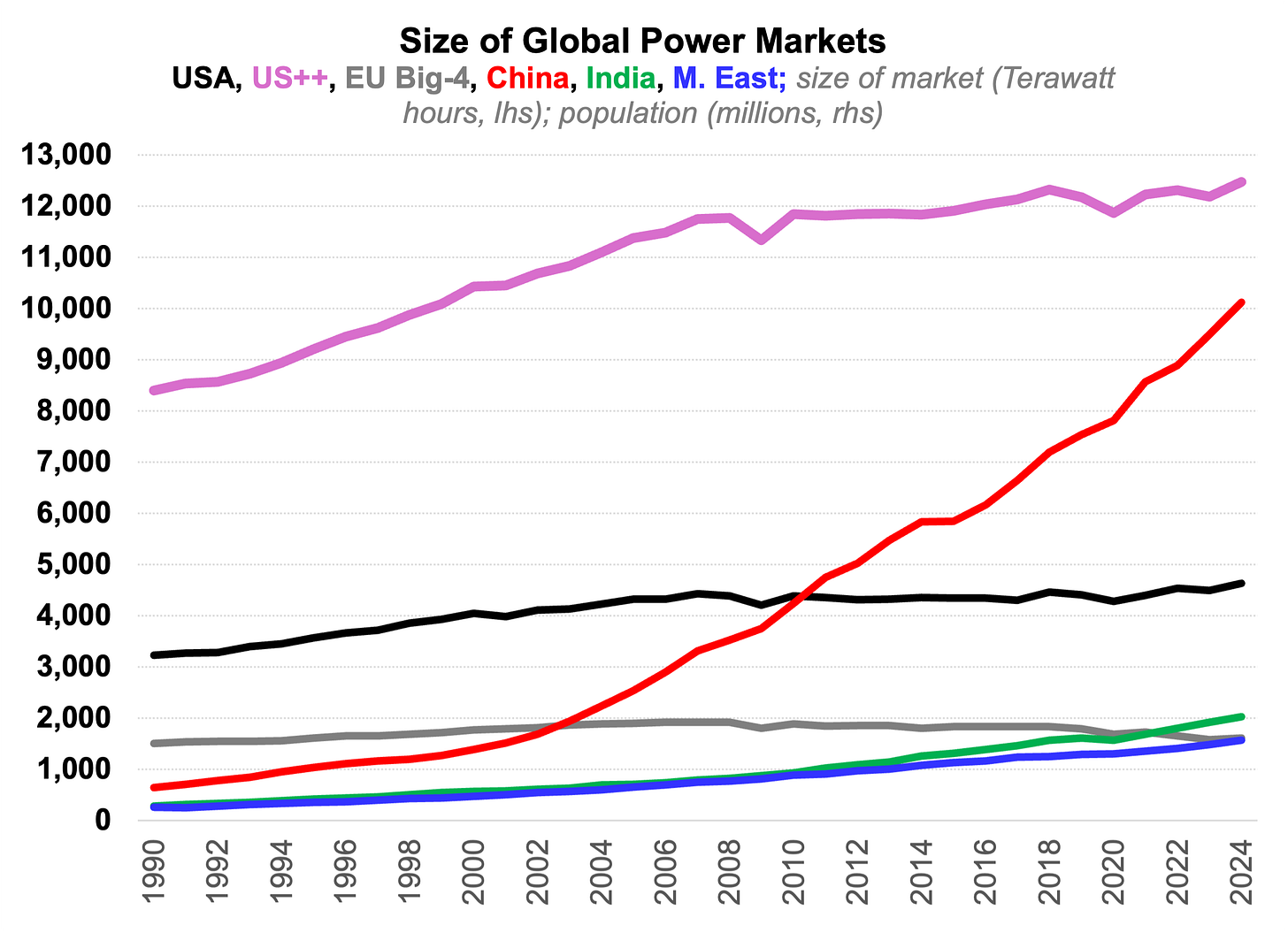

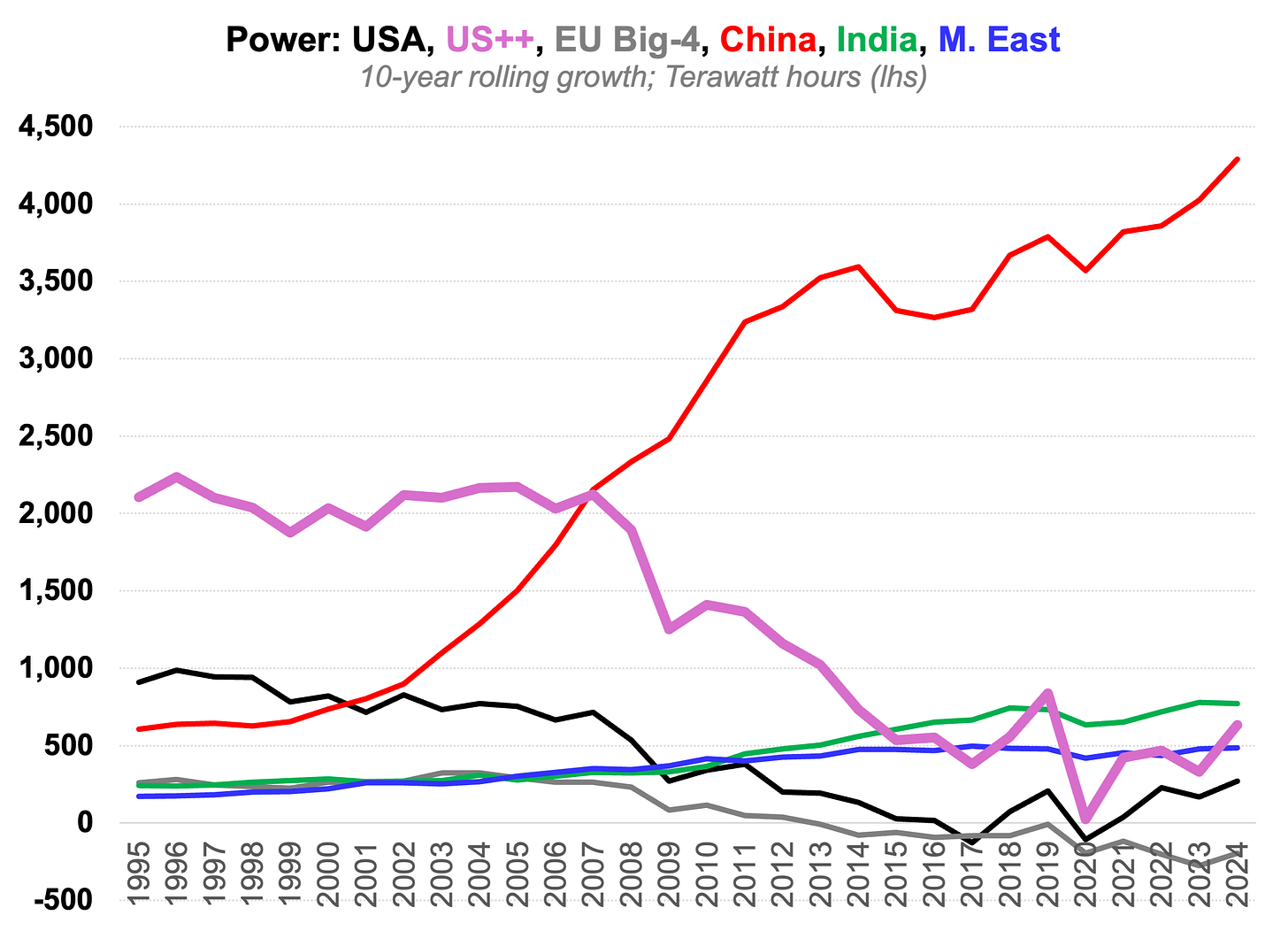

As we discussed in a December 6, 2025 post (here), China has a massive power capacity lead over every other country or region—it’s not a close call (Exhibit 1). That lead is on-track to expand as China is also growing at many multiples of every other major country or region (Exhibit 2). The U.S. is moving from no-growth to at least some growth mode, which we believe will be confirmed in 2026.

Based on forecasts we track from the likes of Goldman Sachs Research and similar firms (banks, consultants, agencies), we believe U.S. power market growth could rise to a level where it is growing at about one-third-to-half the rate of China over the next several years. While that would imply the U.S. is still losing ground on an absolute basis, it would represent a marked improvement from where we’ve been.

Exhibit 1: China’s power market is at an absolute size that is well in excess of everyone else

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

Exhibit 2: China’s power market is also growing at a rate well in excess of everyone else

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

P3: Will oil experience a cyclical rebound, move to a new super-cycle, stay weak, or crash in 2026?

A: Cyclical rebound.

We think we have pushed back on the “oil glut” narrative enough that we don’t need to write a treatise on it in this post. We have believed that between the latter portion of 2025 and the first half of 2026, oil markets would experience a modest oversupply but not a glut. It remains our view that the combination of improving global GDP noted earlier coupled with a leveling off by mid-year of both non-OPEC and OPEC supply growth, oil prices would rebound in 2H2026 or 2027. This remains our base-case.

In order to call for a new oil super-cycle, which we are not doing at this time, we would need to see much stronger oil price-insensitive global GDP growth such as was experienced during the China/BRICs expansion period (2004-14) coupled with an inability for supply to easily keep pace with that growth. While we are positive on global economic activity, we do not know if 4%+ growth is possible. It is also our view that in major oil supply areas like shale oil in the United States, if oil prices were to rise to levels above $75/bbl or $80/bbl, a supply response would be likely.

CORPORATE STRATEGY

P4: Will power move from “hopes and dreams” to “execution” phase of its super-cycle?

A: Yes.

We are fans of the framework our former Goldman Sachs colleague Brian Singer used to use to describe where we were in the shale oil cycle that he is now applying to AI and power (discussed on a recent COBT podcast here). The basic view is that the “discovery” and “hopes and dreams” phases of the cycle lead to material share price and valuation expansion but that the execution phase is more challenging and there is a need to discern those that are executing well versus those that may struggle.

Using that framework, we think of ChatGPT going viral in November 2022 as “discovery” and much of 2023-2025 as the “hopes and dreams” phase where growth rates and expectations for a new power super-cycle were raised. An example of “hopes and dreams” would be the significant market capitalization expansion of pre-revenue power technologies such as companies exposed to small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) and the generally better trading multiples we have seen across a broad range of companies exposed to the power sector (i.e., including those that have current EBITDA and legacy businesses).

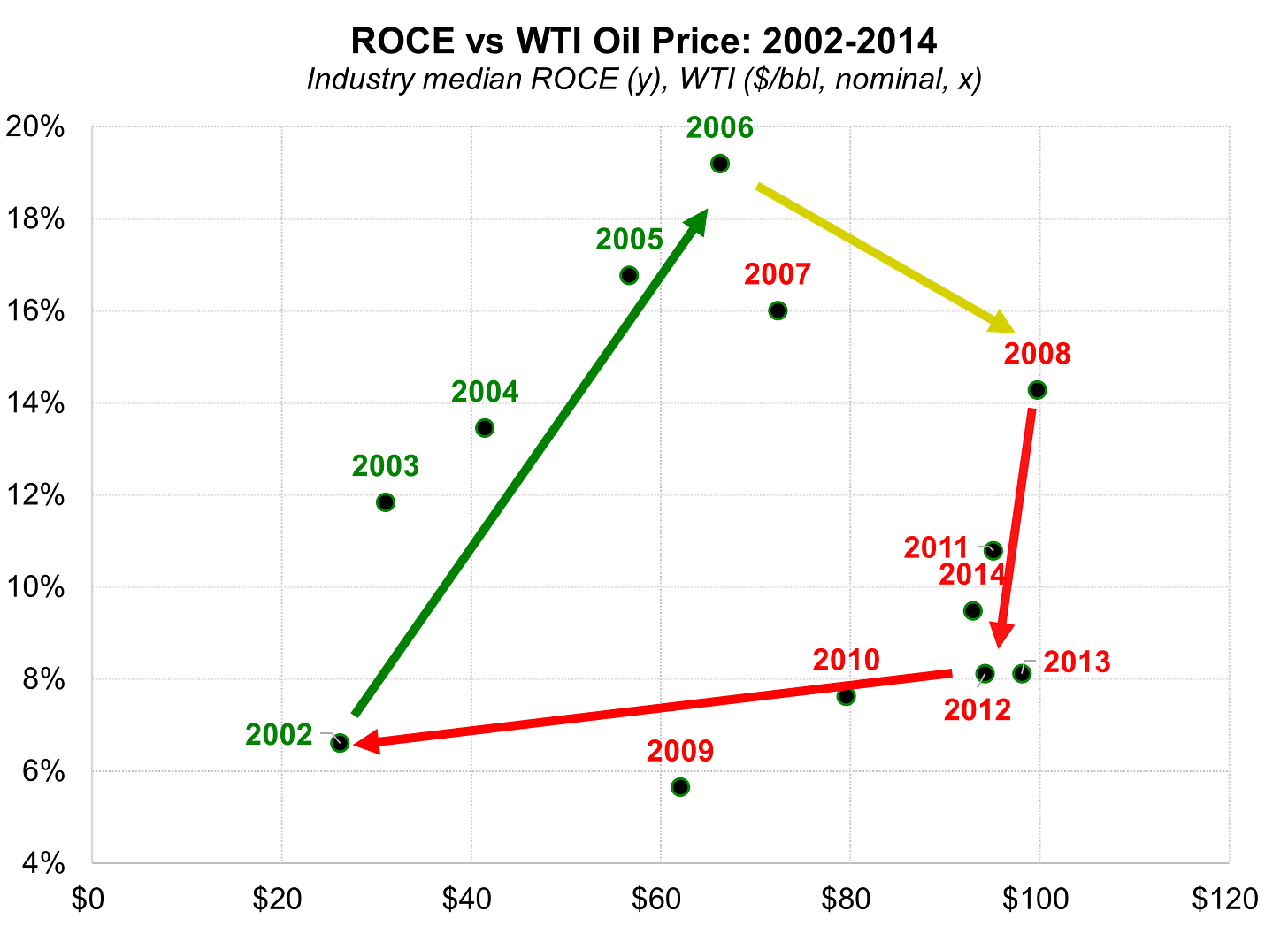

We have written extensively about challenges in execution in the oil & gas space during the “Super-Spike” era of 2004-2014 using our “Quadrilateral of Death” framework (Exhibit 3). We observed that the erosion in the relationship between WTI oil prices and corporate ROCE (return on capital employed) was the warning sign that the oil cycle was long in the tooth from a value creation perspective. Given the very different nature of power markets versus crude oil, we suspect that it won’t be a commodity price versus ROCE metric that will be the early warning sign. We have not yet come up with what the equivalent analogue will be in power and welcome any feedback from those of you with greater expertise in power have.

Exhibit 3: We use our “Quadrilateral of Death” framing for oil and natural gas super-cycle analysis…what is the equivalent for power?

Source: FactSet, Veriten.

P5: For traditional energy companies, what areas of risk-taking do you expect to see?

A: (1) Upstream: a return to international E&P/exploration; (2) Oil Services: continued power market expansion.

We are going to focus our risk-taking question on the traditional oil & gas sector, which we can speak better to than speculating on what power-oriented companies may or may not do. While we still see substantial opportunity in U.S. shale, we think 2026 will mark a notable and observable shift of upstream companies and investors going back overseas—something we have not really seen since the end of the Super-Spike era and the concurrent rise of U.S. shale oil in 2014. We believe this kind of business development will prove to be the more notable trend than M&A activity, though there is always an ongoing flow of the latter.

A quartet of pressure pumping oil services companies have led the charge on pursuing mobile, modular, and distributed power generation. We expect that trend to continue. Whether upstream natural gas, midstream, or refining companies make similar moves is something we will of course monitor, but we do not have enough conviction at this time to predict it will be a major 2026 theme.

MARKETS AND SECTORS

P6: Will the energy sector and will the power/utility equities in the S&P 500 see an increased weighting in the S&P 500 in 2026?

A: Yes and yes.

We are going to use our Director of Research experience to critique ourselves for repeating a “yes” call on traditional energy and then introducing a “yes” call on a sector we didn’t directly cover during our Goldman Sachs analyst days. “Arjun, are you an oil & gas equities perma bull by always forecasting a rising S&P 500 weight including last year when you actually (and correctly) expected oil prices to be soft? And what do you really know about power and utilities to suddenly declare a rising S&P 500 weight? And you certainly are not an expert on every other S&P 500 sector to de facto imply a reduced weighting in Magnificent-7 or other large sectors.”

Typical analyst response to a DOR: “Stop micromanaging me. I am going to make whatever call I want to and there is nothing you or any other management bureaucrat can do about it. Sure, I have specialized, narrow knowledge. But that will never stop me from talking about a much broader range of subjects—directly or indirectly, intentionally or not. Go to H—l and pay me more.”

Nothing like remembering the good ole days of being a DOR. And since we repeatedly state our ongoing self-identification as an “equity research analyst,” we are feeling especially good about our “yes” and “yes” call.

P7: Can US coal become great again? Or at least join natural gas and nuclear power generation as areas that were out of favor and have regained investor and corporate interest?

A: Great is probably too strong of a word as it’s likely a longer path back to rich-world re-acceptance. However, we do see the potential for a coal comeback in the U.S.

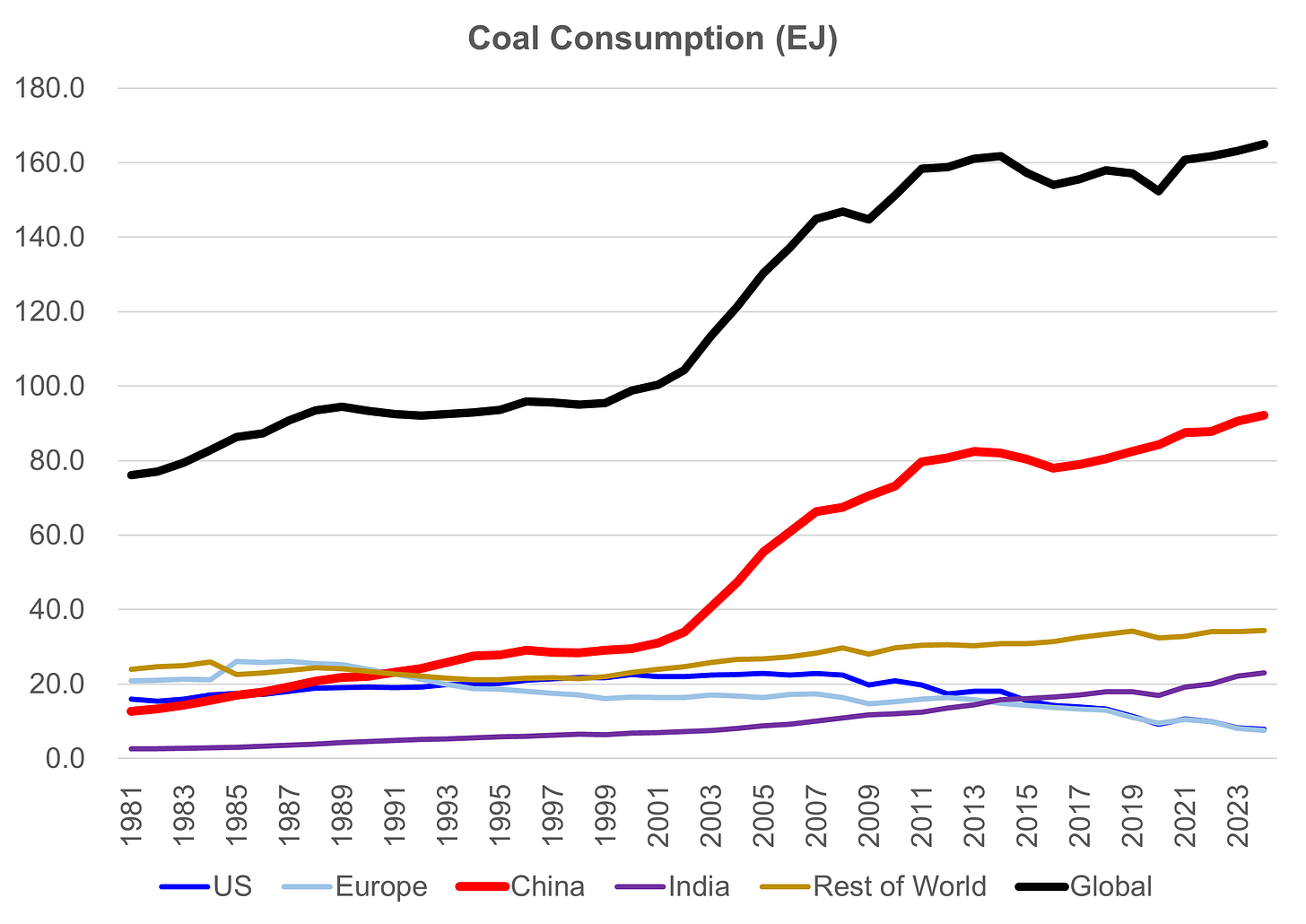

The over-arching question we are asking is can U.S. power markets grow significantly faster without at least some form of a return to coal, which has been a bedrock to power market expansion—historically in the OECD and currently in areas like China and India (Exhibit 4). We are not expecting to return to the types of market share it enjoyed in decades past prior to growth in natural gas and renewables. But won’t we need at least some coal to return, especially to help address affordability and reliability questions?

Exhibit 4: China’s manufacturing strength underpinned by its power market strength which has underpinned by its dominance in world coal markets

Source: Energy Institute, Veriten.

There are a variety of reasons, not least of all the competitiveness and massive availability of natural gas, that suggests the United States will not be following in China’s path of a massive expansion in coal-fired power generation. But the Trump Administration has been (we think correctly) focused on halting what had been a multi-year trend in coal plant retirements. Furthermore, we believe similar to our view on crude oil and natural gas that the U.S. should look to promote the export of its coal resource to countries that are seeing rising demand for coal-fired power generation.

In sum, we are not anticipating that in 2026 coal will fully follow natural gas and nuclear down the path of broad-based acceptance in the United States. However, we do see it continuing to turn the corner from being shunned and left for dead to instead being a recognized and appreciated component of a healthy energy mix.

GEOPOLITICS & POLITICS

P8: Will we see Chinese EVs in Europe and the US in 2026 in noticeable quantities?

A: Yes to Europe, no to the U.S.

We define “noticeable” as meaning the volumes are sufficiently large to not just be a topic of political discourse, but that there are visible impacts on the outlook for legacy auto makers in the region (e.g., forecast or actual sales decline and domestic factories close). We view the Chinese EV versus legacy auto OEMs issue as an example of China’s manufacturing dominance and the threat it poses to companies and industries in the OECD.

We appreciate that there is considerable political rhetoric to re-shore and bring industries and jobs back home. The challenge in the near-term and really the next decade-plus is that China has a massive lead that is only growing. The willingness of countries to allow, or not, “cheap” Chinese EV imports we see as a great test case as to how serious a country is to re-shoring or, as the case may be, defending existing industry so it is not competed away.

P9: How will war and geopolitical disruption risk impact energy commodities?

A: There will be a growing appreciation for the strategic value of owning/controlling both raw commodities and the refining of those inputs into usable end products.

For energy commodities like crude oil, the geopolitical lens is often viewed through the “what does this mean for crude oil prices” prism. We appreciate that there are supply impacts that need to be accounted for, but, as we discussed in last week’s video podcast (here), the structural bull/bear/neutral outcomes point to the need to understand the broader context under which geopolitical turmoil is occurring.

We see the Venezuela incursion as an additional catalyst to oil importing countries to recognize the strategic value of controlling crude oil reserves. Higher levels of stocks including strategic petroleum reserver (SPRs) and ownership of resources in foreign countries—a trend we saw during the Super-Spike era—we believe is in the early days of returning.

As the world order evolves, there is no substitute to a country controlling both the raw inputs and commodity refining capacity it requires. This is also a catalyst for new technology development, something we of course have also seen via the significant growth in EV and LNG truck sales in China.

ENVIRONMENT & SUSTAINABILITY

P10: Will Venezuela serve as a wake-up call to the moderate-left-of-center in the United States about the often greater environmental challenges that exist with oil, natural gas, and coal developments outside of the United States, Canada, and Western Europe?

A: It certainly should, but we will go with “no” as far as 2026 goes.

To be clear, we would be pleasantly surprised but in no way expect the moderate-left-of-center to become pro oil & gas as some (on the moderate left) have recently argued. But there is a chance, perhaps small, that the conversation will shift—to use their terms—to “responsible domestic oil & gas development” from “keep it in the ground” (which comes from the activists but doesn’t receive vocal pushback). Again, we are referring to the moderate wing of the left, not the progressive activists. A follow-up question might be: “are you being delusional right now?” Maybe. But, and perhaps it is a plea more than a prediction, there must be a politician(s) somewhere that can stand up to the worst ideas of the loudest voices in their party.

On this point specifically, we were surprised to see an article in the New York Times (here) that noted how much worse environmental practices have been in Venezuela versus the United States. There may be many reasons for this article unrelated to an awakening on the US oil & gas industry’s better environmental performance vis-à-vis Venezuela. But it’s a start.

⚡️On A Personal Note: The D.O.R. Chronicles

It was the job that convinced me I should take early retirement from Goldman Sachs: co-managing the Americas Equity Research department from 2012-2014. I often allude to it in Super-Spiked or in my remarks at various events, but I don’t think I’ve really dug into that 3-year stretch of my career, which marked a major transition from being an energy sector equity analyst to ultimately my subsequent roles as a corporate board director, advisory board member, private equity senior advisor, and now a partner and full-time employee at Veriten.

I had resisted the “do you want to join management” calls for a couple of years. But by the time 2012 rolled around, the idea of at some point having to live through the inevitable extended energy downcycle seemed unappealing. Worst of all, my desire to aggressively service our institutional investor clients had diminished—even to the very nice ones that I loved interacting with. So I finally caved and agreed to join the management ranks.

I still remember one of my first 1:1s with Goldman’s then global DOR who had been a key mentor of mine since I joined the firm in 1999. “Arjun, now that you are part of management, you have to stop referring to management as a bunch of bureaucrats.” It was good advice that never quite sunk in for me. I am inherently a small government kind of person. And while we did make legitimate attempts to find a replacement to take over my integrated oils and refiner coverage, after missing on a hire or two, I ended up being a player-coach for my 3 years in the DOR job.

The worst parts of being a DOR: (1) compensation season; (2) HR matters; and (3) fighting with other areas like sales and trading about resource allocation and servicing clients. But as I look back now, there are some clear positives that came from that role:

I am not sure I would have taken an early retirement from Goldman in 2014 had I remained just a covering equity analyst. I would have missed all of those middle and high school years with my kids.

I have loved all the post-Goldman roles I’ve had, all of which, I believe, have made me a better analyst.

Managing a much larger organization than simply a typically small coverage team (usually 3-4 people in total) or even a sector business unit (25-50 people) was really good experience in hindsight.

At the time, I was not comfortable with having oversight responsibility for analysts in non-energy sectors. Having to trust someone else’s work where I did not instinctively understand the macro or company-specific fundamentals was incompatible with my “you always have to crunch the numbers’s yourself” equity analyst mindset. Over the years, I have gotten much better at being able to sort through analysis/commentary that I can trust versus those that I cannot, without having to crunch all of the numbers myself.

The human resources side of the DOR job was pure torture at the time, both compensation season and having to deal with all the personal stuff that people do that management has to weigh in on. With hindsight, that people management side has come in handy both in terms of thinking about resource allocation and having a view on people behavior. Our energy team was close knit and I worked very closely with all of them. It’s not possible to be as close to everyone in a much larger organization, especially when its spread across different cities and countries. Still, with less than perfect insight, you have to make decisions on people or situations, something the Goldman co-DOR role has helped me with.

Would I do it the same all over again? Hard to know but I wouldn’t want to change any of the forward path I did take, so probably not.

⚖️ Disclaimer

I certify that these are my personal, strongly held views at the time of this post. My views are my own and not attributable to any affiliation, past or present. This is not an investment newsletter and there is no financial advice explicitly or implicitly provided here. My views can and will change in the future as warranted by updated analyses and developments. Some of my comments are made in jest for entertainment purposes; I sincerely mean no offense to anyone that takes issue.

Thanks, Arjun! That was thought-provoking. Here is one suggestion for the power-related chart. Use the price of generators in place of WTI. Generators are the major essential element for baseload power.

It has been really fascinating to watch the level of detachment from reality exhibited in a large fraction of the reactions to changes in Venezuela. My prediction is that no matter what that will be a long story.

In my case, I resisted serious management roles during my time in the big lab. But 20 years later a roomful of academic colleagues looked at me and said I had to be the leader of a major Center. So the management bureaucracy never got me but academic democracy did.

Always appreciate you sharing pieces of your journey, not just your insights and frameworks for the energy world. Makes a much more holistic and thoughtful landscape.